Earth’s north magnetic pole is heading for Russia

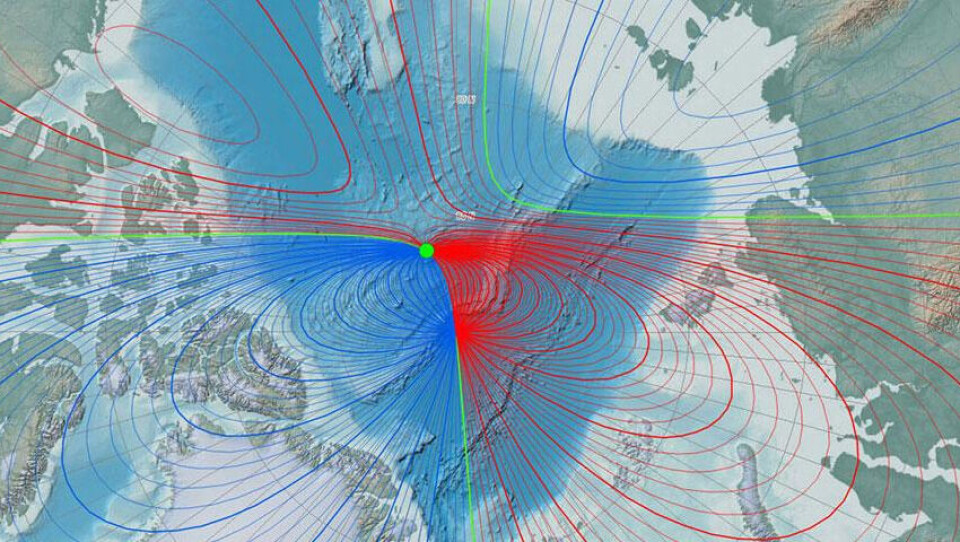

The direction indicated by our compasses, the magnetic north pole, is not fixed, unlike the geographic north. In fact, it is moving pretty fast and even more in recent years.

Text by Mathiew Leiser

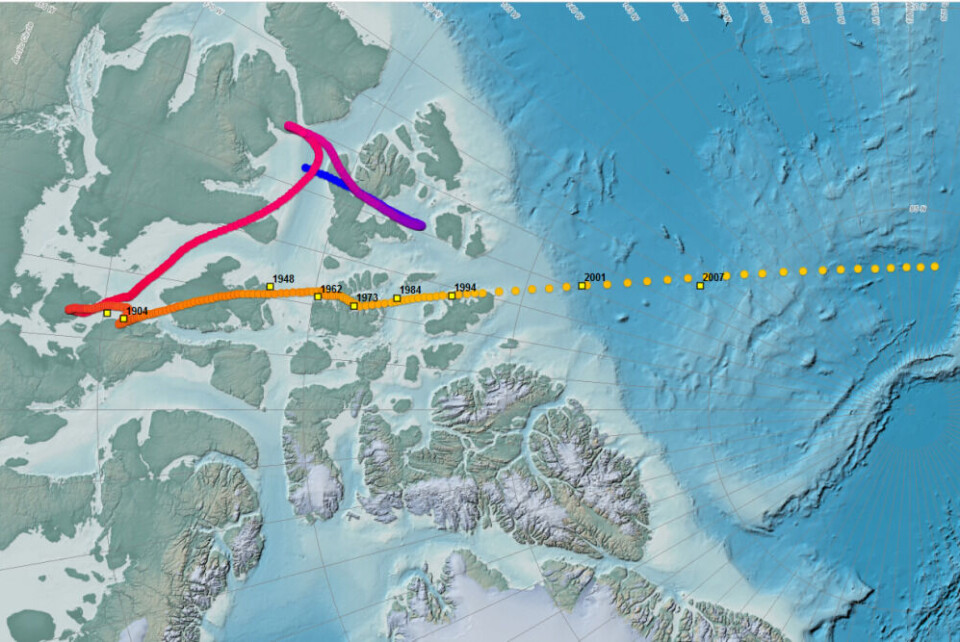

Since its official discovery in 1831, the north magnetic pole has been slowly moving across the Canadian Arctic towards Russia, travelling some 2,250 km. Scientists could then follow it fairly easily because of its pace, but that has changed since the turn of the century, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information.

Over the past 20 years, the speed of the north magnetic pole has gone from 10 kilometres per year to 50 kilometres. In September 2019, magnetic north even aligned briefly with true geographic north (where all lines of longitude converge at the North Pole) as it passed over the prime meridian.

This was the first time since about 1660 that the compass needle pointed directly to true north in Greenwich, London (where the prime meridian is located) before slowly turning east. As the prime meridian, the north-south line at Greenwich is used as the reference for all other meridians of longitude, which are numbered east or west of it.

This acceleration forced scientists to update their forecast of the planet’s magnetic field one year ahead of schedule. The World Magnetic Model (WMM), developed by the National Centers for Environmental Information and the British Geological Survey, is usually published every five years. This time, however, they had to release an out-of-cycle update in February 2019.

This is only the second time in recorded history such update is published, according to the British Geological Survey (BGS).

Magnetic north has left Canada for Russia

In December 2019, the teams of scientists finally published the full WMM, which will run until 2025.

The report forecasts that the northern magnetic pole will continue drifting towards Russia, although at a slowly decreasing speed—down to about 40 km per year.

“The recent changes of the field have been of particular interest at high northern latitudes, as since the 1990s the motion of the north magnetic dip pole has accelerated more quickly than at any point the last 400 years,” explains Dr. Will Brown of the BGS Geomagnetism Team in a blog post.

If the pole continues to move as scientists predict, “by 2040, all compasses will probably point eastwards of true north,” said Ciaran Beggan, a scientist from the BGS in a press release.

The magnetic poles’ movement is not fully understood by scientists. The main assumption is that since the Earth’s magnetic field is created by its constantly moving, molten iron core, its poles are not stationary and they move independently of each other.

The Earth’s magnetic field consists of a kind of bubble made of geomagnetic energy that protects our planet from radiation coming from the sun.

Crucial for navigation systems

Knowing where the magnetic north is is essential for the proper functioning of our navigation systems.

Any updates to the WMM are closely monitored by European and American militaries, since their navigation systems rely on it. Organizations such as NATO, the UK Ministry of Defence, and the US Department of Defense as well as smartphone operating systems such as Android and iOS and commercial airlines all rely on this report.

The WMM consists mainly of a list of numbers that enable devices and navigators to predict the behaviour of the magnetic field. This allows us to estimate where the magnetic field will be at any given time within the next five years.

“Technology from planes to cars, smartphones to drills for hydrocarbon exploration rely on the WMM behind the scenes, and many of us use it every day without ever realizing!” writes Dr. Brown in his blog.

Airport runways are a concrete example of a navigational aid updated to adapt to variations in the Earth’s magnetic field. US airports use WMM’s data to “give runaways numerical names, which pilots refer to on the ground”, explains the National Centers for Environmental Information on their website.

However, when we consider our daily lives, changes in the magnetic field do not affect us as much as we might think.

“Compasses and GPS will work as usual; there’s no need for anyone to worry about any disturbance to daily life,” said Dr Beggan.

Those really affected are only the directional drilling companies and the U.S. Department of Defense, he added.

These drilling companies use compasses and magnetic fields to guide drill bits. The Department of Defense, meanwhile, wants as much accuracy as possible for the navigation systems of its planes, submarines and parachutes.

This story is posted on Independent Barents Observer as part of Eye on the Arctic, a collaborative partnership between public and private circumpolar media organizations.