“It shows that the emperor has no clothes,” interview with The Moscow Times editor

We spoke to the American journalist Samantha Berkhead, the editor-in-chief of the Moscow Times English language service after her news outlet was outlawed as “undesirable” in Russia.

The “undesirable” label means that a criminal case can be opened against anyone who is associated with The Moscow Times now. Many other Russian media outlets, such as Meduza, TV Rain, and Radio Liberty, have also been labeled “undesirable” by Russian authorities.

The Moscow Times had been based in Russia for 30 years before it had to relocate its staff to Amsterdam, Netherlands, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Over the years, The Moscow Times has been the starting point for many prominent reporters from around the world who have set out to cover Russia. For example, the American journalist Evan Gershkovich, who was sentenced to 16 years imprisonment in Russia today, also began his career in The Moscow Times.

The Moscow Times is labeled as “undesirable” by the Russian authorities and the official statement says: “The work of the outlet is aimed at discrediting the decisions of the leadership of the Russian Federation in both foreign and domestic policy,” How do you understand that?

Samantha Berkhead: I was surprised it didn’t happen sooner. For a long time, we’ve been operating under the radar. We were obviously doing the coverage that was bothering someone in the leadership of the country. I think Russia is just weaponizing this language of “discreditation” to suppress any descent. But not even descent, any sort of coverage that sheds light on the aggression and the bad things the country is doing to its own citizens as well. Clearly, their goal with this is to silence us and to make it even harder for us to do our jobs. This kind of coverage when it reaches Russia, it shows that the emperor has no clothes.

What kind of difficulties are you facing now after being labeled “undesirable”?

The most immediate concern for me is the safety and security of all our people in Russia. There are a few fixers and people on the ground. Everybody who works for us inside Russia has to weigh the fact that they now face criminal prosecution if they are discovered. So now it gets even more precarious for them.

Now it’s extremely difficult as any sign of cooperating with an undesirable organization is punishable by prison time. If you identify yourself as a journalist for The Moscow Times, people say “I can’t speak to you, because it puts me at risk”. It just means we have to work even harder. I think it’s important to underscore the bravery of people who do choose to speak to us despite facing that.

You have almost two dozen staff members, who are based now in Amsterdam, the majority of them are Russian citizens. What measures do you take for their safety?

The Russian staff are thinking now what to do. If they continue to work with their own name… Actually, a lot of Russian staff have worked anonymously before (the Moscow Times was labeled “undesirable”).

But now, even if they work anonymously, if they go home to see their family in Russia, they are at risk. It’s really tough. We’ve all been at risk since the start of the war and since we left. But now it is very black and white what we are facing.

On your website in the credits it has no name and says “By The Moscow Times reporter” - is it one of the measures now to protect your staff?

Yes. That’s one of the ways. It’s a matter of trust with the audience. They need to trust that a real person is writing this.

It is still possible for a criminal case against someone to be open in absentia.

And then if they go to a country that has an agreement with Russia - for example, Serbia or Armenia - they can be extradited to Russia where they would be put in prison. I can’t disclose all the security measures we are taking now though.

You launched your Russian language service in January 2022 - just a few weeks before the invasion of Ukraine. What is the audience of the Russian service now?

Our English service audience is about 1 to 2 million a month. The Russian reaches about 5 million a month. But on Telegram, for example, they even have a wider audience - (97, 390 subscribers by the time the interview was published). On the website, we usually see huge spikes in visitors after, for example, such events as the Wagner mutiny or the Crocus Hall attack.

But I think the part of the problem we are grappling with now is that the world is moving on to other things. Interest in the war in Ukraine is weighing. We are struggling with how to keep people’s attention on this. And make our journalism still relevant to people.

Why do you think your Russian website is more popular than the English one?

Because I think it is one of the only sources of information about what is actually going on in their country. After the war started so many independent outlets had to shut down or reduce their reporting capacities.

About the international audience. What do you think is important to explain to the world about what’s going on in Russia now?

Before the war, I thought my mission was to show English speakers all over the world that there are so many facets of Russia. That there are good people and bad people. There are brave people, there are evil people. Just to show them that that is not one-sided and it’s not a caricature that we’ve been given by a lot of media outlets. Especially in the US. And then the war started. I was very like - “Well, what do I do?”

But I still feel that that mission is relevant, even though there is this horrible war happening. When the war ends, we will have to still engage with this country in some way. We will have millions of people from this country…

If we don’t understand them and we don’t understand how their society has been transformed by the war, it’s gonna lead to a lot of problems.

How has Russian society been transformed by the war, based on your experience covering it?

I think it starts from a very young age - there is a lot of militarisation with education.

Children are being taught how to assemble weapons and drones. And they are reading schoolbooks that have this very warped vision of history based on the Kremlin’s idea of Ukrainian statehood …

Any form of descent is no longer possible. Even if it’s something very minor. Even if it’s wearing a blue and yellow T-shirt - you can get fined. Women’s rights are being limited because the country is trying to increase the birth rate. So abortion rights are being targeted in several regions. There is pressure from the Kremlin to make society conform to its vision. You see it with LGBTQ rights. It’s not possible to express yourself in that way at all. If you are found to be displaying LGBT symbols, that is considered an extremist symbol now.

What recent The Moscow Times report would you highlight? The one you’re most proud of now?

For me personally, for example, last month I did an interview with Nadia from The Pussy Riot. That was very cool because she was one of the people who was a huge inspiration for me. Getting to meet her and kind of almost bond over interests. That was awesome.

In terms of our coverage - for example, the exclusive report by Pyotr Kozlov about how Putin wears body armor on the Red Square and he has people tasting his food. It’s kind of this “juicy” story, but it’s also very indicative of the mindset in the Kremlin.

You’ve been based in Russia for 3 years, now in Amsterdam. Reporting about Russia from outside - does it make your work unreliable if you are not on the ground?

I don’t think so. We are not alone in this struggle finding credible information from outside. We have had two years to figure out how to get sources and how to find stories on the ground even if we are not physically there.

But it’s something I grapple with every day. This feeling like: “Am I credible?” “Am I trustworthy?”.

Because I’m not there and I’m not seeing things with my own eyes. But it’s the best I can do. I think our readers trust us to be able to discern reality from inaccuracy.

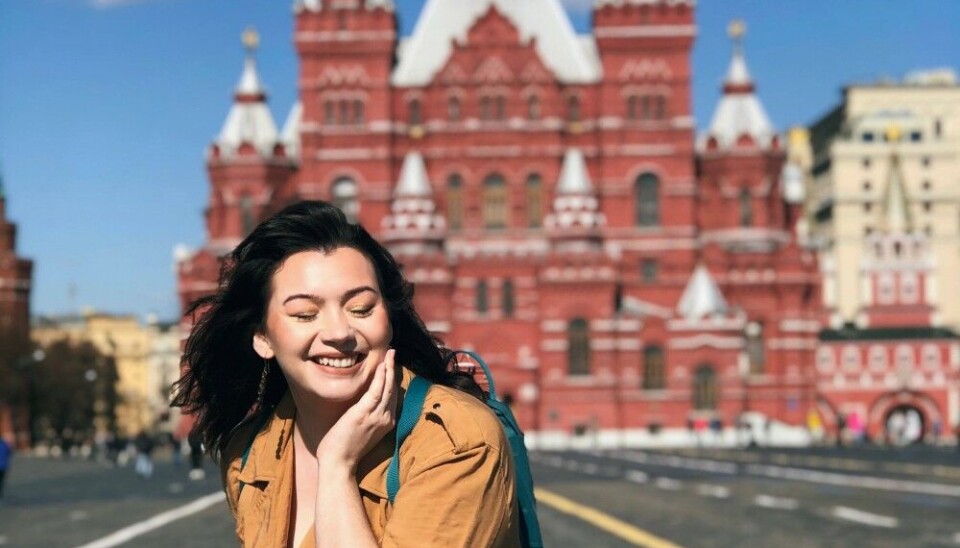

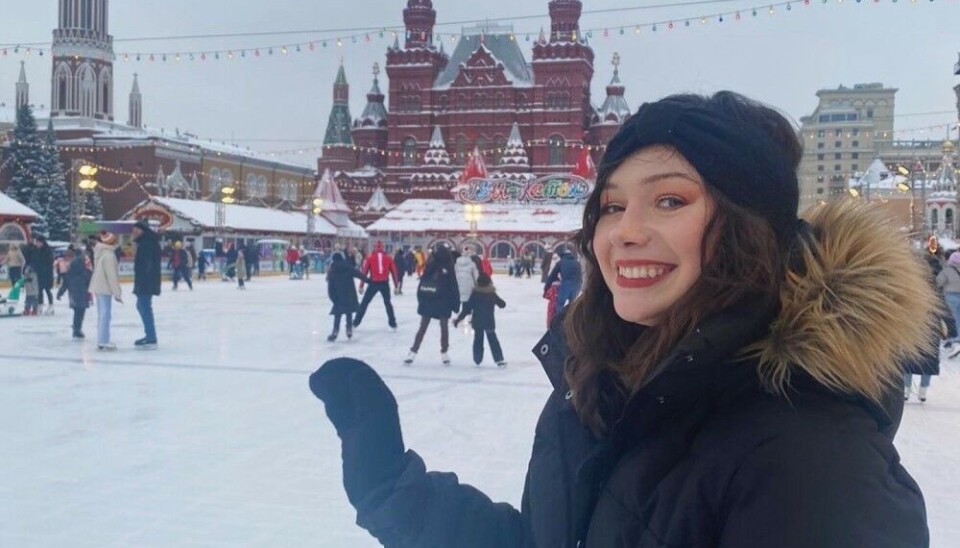

After those 3 years being based in Moscow before the war, what do you remember about it?

It was amazing. It was a place - very modern, also just the people I knew were so welcoming. You could walk into someone’s house - someone’s grandma. And they would just feed you. A lot of memories of conversations with people - you meet someone for the first time and end up speaking to them till 3 a.m. about really deep life topics.

I was stuck in Russia during Covid time, so I was able to travel all around there - I had nowhere else to go. I saw Siberia, the Urals region, I saw the Sochi city, the Caucuses, I saw Karelia, Kaliningrad. Just seeing the diversity, the beauty, the nature, the richness of all the different cultures. That’s what I miss.

Meanwhile, Russian state propaganda regularly blames Western elite and journalists for “hating Russia”, and for being “anti-Russian”. Such a term as “rusophobia“ and “fake news” are regularly used to label any independent coverage of Russia. What would you answer to that?

I think it’s very cynical to see everything in that light. But I think that’s how they maintain their legitimacy at home. When you know your regime is built on the media system when Russia state media and everything is controlled, then it makes sense to tell your country and your people that everything else is fake. The answer to that is to prove them wrong and not give them that one-sided coverage be produced.

I don’t think it’s possible to hate the whole country. There are so many different people. You can hate one person. But not the whole country. I don’t ever act out of hatred. I act out of mission to do good and to tell people stories. None of that is motivated by hatred of Russia.

It’s a very ethical thing. I don’t see how it could be right to tell good stories from Russia when children’s hospitals are being bombed in Ukraine.

It seems like it would be a dissonance. But you can cover small victories from a solutions standpoint. For example, when citizens somewhere in the Russian regions are coming together to make their community better because the government wasn’t gonna that for them. I think we have always covered grassroots victories like that.

Working outside of Russia, I often hear one question - “Why don’t Russian people protest in masses against authorities”? What would your answer to that be?

It’s important to know that they are not protesting because if they do, they immediately will be thrown into prison. There are a lot of people in Russia who fall victim to propaganda. There are a lot of people who are apolitical because they have always been. But they are humans and humans are complicated. That’s why there needs to be a dialogue. I think it’s also important to underscore that people are still showing resistance but they do so in silent ways or ways it’s safe for them. Like, writing slogans in public places - like graffiti or whatever. That’s all they can do. But it’s still extremely brave cause even that is risky.