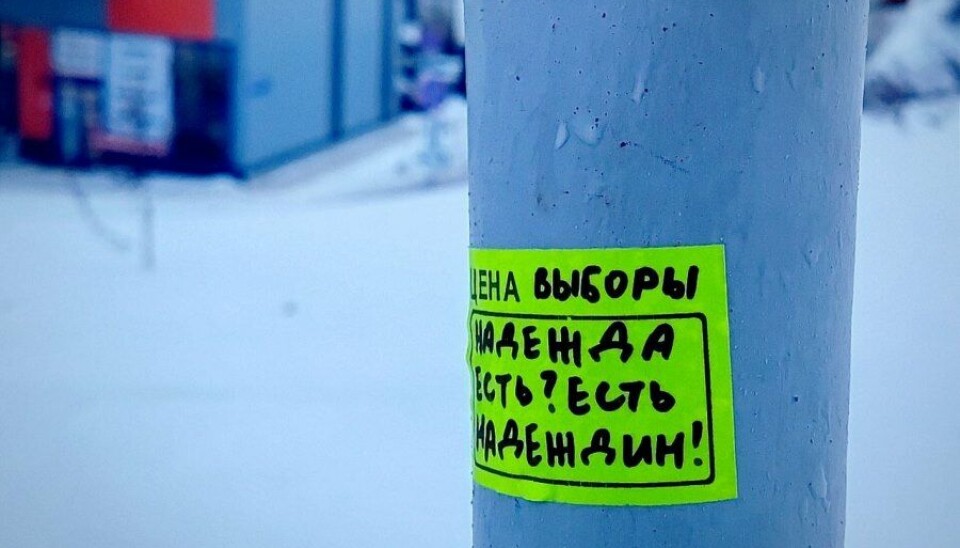

Russians stand in lines and travel hundreds of kilometers to sign up for Nadezhdin, the presidential candidate with an anti-war agenda

The Barents Observer spoke to those collecting signatures for Boris Nadezhdin, the only Russian presidential candidate who promises to end the war in Ukraine and free political prisoners. The police are interested in activists, people travel from other cities to sign for Nadezhdin, and the procedure itself is called a legal way to protest against the war and the Putin regime.

“People feel that a very serious issue of country’s future is at stake. This issue will affect everyone personally in one way or another. Many people are unhappy with the ruling regime, and [signature] collectors are motivated to change the situation. We have a pensioner in a village, people come to see him. He has already collected 40 signatures this way, this is a good result” says activist Roman Ivasko in Syktyvkar, the capital of the Russian northern region of Komi.

Ivasko is now the main organizer of collecting signatures in support of Boris Nadezhdin in Komi. Previously, Roman was the organizer of a referendum in support of the return of direct elections of the mayor, but the Komi State Council refused to hold a referendum.

“On January 10, we opened a signature collection point in one of the shopping centers, and the process began. At first it was slow, we collected 7 or 8 signatures in the first few days. On a Saturday we collected 14 signatures and said: “Wow, it was a good day.” And the day before yesterday we collected as many as 250 signatures on a weekday, this is a record,” says Roman.

According to Russian law, a presidential candidate must collect a certain number of signatures to get on the ballot. Boris Nadezhdin, as a candidate from the Civil Initiative party, needs 100,000 signatures. Nadezhdin is a municipal council member in Moscow; he had almost no federal recognition until he announced his intention to run for president last October.

Boris Nadezhdin is the only candidate who declares the need to end the war and pardon political prisoners in his election program. Before him, a journalist from the Tver region, Ekaterina Duntsova, wanted to enter the presidential race with the same slogans, but the Russian Central Election Commission refused to register her. Duntsova, who by that time had received great public support, called on her supporters to support Nadezhdin. So did many other opposition politicians and associations.

Photos of lines at signature collection points for Nadezhdin began appearing in mid-January. The telegram channel From Karelia with freedom published a snapshot of the line in one of the shopping centers in Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, another northern region.

“I was very impressed and touched. The first time I collected signatures in the store thirty people came. I thought I would do it for half an hour, but in the end I worked for one and a half hours. I was very inspired,” says Irina, one of the signature collectors in Karelia. Her name has been changed at her request.

Irina says that all kinds of people come to sign for Nadezhdin.

“Scientists, teachers, librarians, IT specialists, students, pensioners, entrepreneurs, lawyers. There are also state employees. There was a man who was born in 1958; I told him that I was very happy that he came to sign. He replied – I’m not brainwashed, I don’t have a TV.

I got the impression that people have the same motive: “It’s impossible to tolerate all this.” Everyone hopes that Nadezhdin will be registered. Some say “Nothing will change anyway,” but they still come. The emotional background is depressive, people don’t want to get their hopes up, but they still come. “At least we’ll try to change something, maybe my signature will help.”

“Many people feel a closeness of views with Boris Nadezhdin. Naturally, the desire for a truce is a factor, too. Many are already tired of the ruling regime, people are angry with it. This is not the majority, but still a very large part of society. There is a demand in society, and it is being realized through signatures for Boris Nadezhdin,” says Roman Ivasko.

Even those who do not believe in the Russian elections and are skeptical about Nadezhdin himself are signing.

“Of course, we all are perfectly aware of the value of the current elections. But I, like many, signed for Nadezhdin for one simple reason: this is the only legal way to express my position,” Karelia-based journalist Evgeniy Belyanchikov, an ex-chairman of the regional Journalist Union, explains. “We see that there is a demand for peace in society; and the Kremlin has given people the opportunity to express it. Nadezhdin’s person does not matter; it could have been any other candidate who would take such a position.”

I have a feeling that, of course, Nadezhdin will be barred [from running]. But we live in a time when it is impossible to even plan your life for more than a week, not to mention political processes. People meet in these lines, talk to each other, and get inspired by the fact that there is a demand for the anti-war agenda. That in itself has value,”

– says an activist from Karelia, who also wished to remain anonymous.

“Campaign to identify dissenters”

People are ready to spend hours and even days to sign for Nadezhdin. Collectors travel to remote areas, but still cannot reach everyone.

“They told me about a family which traveled 300 kilometers to sign. Here’s another similar case: a woman from one of the Komi districts came to Syktyvkar to sign, which is almost 200 kilometers away. By the way, she works in the government system. Her superiors told her to sign for Putin, but she refused. This lead to her being “called on the carpet,” which made her even more angry and she’s now going to sign for Nadezhdin,” says Roman Ivasko.

Apparently, the authorities are not happy with the activity. Roman Ivasko told the Barents Observer about police interference in the signature collection process in the town of Ukhta in Komi.

“A woman from the police called me, she’s from some department of public order,” he said. “She wanted to have a conversation with local activists in Ukhta. I asked: “You probably want to give them a notice to refrain from violating public order?” She called me “a smart boy” and said that I understood her correctly. Then, when we found a room for a collection point, the police came there. They asked questions: “Who are you? What are you doing here?” The police took photos of the agreement with the campaign headquarters, as well as signature collector’s notarized power of attorney.”

Signature collector Irina from Petrozavodsk also spoke about problems during signature collection.

“We were kicked out from everywhere,” the woman said. “They threatened us with the police in one of the shopping centers, but the collection time was coming to an end, and we left. We stood in the doorway area, but people were ready to wait and sign, pressing the paper against the wall, because there was no cabinet or desk. I don’t think these are orders from above, it reminded me more of the janitor’s syndrome. Fierce women came saying “Where are your permissions, you have no right!” People wanted to show their power.”

Even though the process of collecting signatures for presidential candidates is absolutely legal, this can have implications in the 2024 Russia, says an activist from Petrozavodsk. Everyone remembers the 2020 presidential election in Belarus, as a result of which Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, who won the vote, was forced to leave the country, and other opposition politicians like Maria Kolesnikova ended up in prison.

“There is fear. A strong one,” an activist from Karelia shares her feelings. “Yes, we can go around and collect signatures for the candidate now, he is not a foreign agent or a terrorist. But at the same time, we know that people are imprisoned because they were once associated with [Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation] FBK. And it’s very scary.”

I don’t understand how to assess my personal risks. How big are they? But I take responsibility; what else is there to do?”.

“I’ve seen fear. And at the same time I’ve seen hope. Everyone is afraid,” says journalist Evgeny Belyanchikov. “The collectors look around, they are afraid of the police. They know how the opposition is persecuted in Russia. Now they seem to be [acting] within the framework of the law, because for the first time in two years people have been given the right to legally express a point of view that differs from that of the state – regarding both the Special Military Operation [an official Russian term for the invasion of Ukraine] and Russia’s future. But everyone understands that after some time they may end up on some list of unreliable people for their opinion. In a way, they came and denounced themselves. Because no one guarantees anything now. I am aware of that too, but I think that we still need to at least express our opinion in this way, to show that the demand for peace is very high in the country and that the public opinion they talk about on TV is far from the real one. And the fact that there are a lot of such people, as these lines show, gives hope. People see that there are many people like them.”

“I joked that this was a special campaign to identify the dissenters. Now they will register everyone and then work [on those leads],” says Roman Ivasko.

The 2024 election is Vladimir Putin’s fifth. To date, it’s been officially announced that 2.5 million signatures were collected for his nomination — this is ten times more than Boris Nadezhdin has collected so far. However, Putin’s signatures were collected with a large number of violations. The Barents Observer wrote about the propaganda of voting for Putin in Russia’s northern universities. If Vladimir Putin wins this election, he will rule until 2030, that will be almost a third of a century. The Kremlin has already stated that they do not consider Boris Nadezhdin a rival to the current head of state.