The FSB has taken a great interest in reading

Security officers have confiscated a book about repressed Finns from the printing house

By Tatiana Britskaya

Matilda Germanovna Khaikara was Finnish. She was born and lived in the village of Belokamenka in the Polar District of the Murmansk region. Karl Karlovich Khaikara, Hemming Karlovich Haykara, Fridt Karlovich Khaikara and Alina Genrikhovna Khaikara were also Finns and lived in the Teribersky district of the Murmansk region. All five were convicted of crimes against the state in 1940 on the basis of order No. 00761 dated 06/23/1940 of the NKVD, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR. Based on their ethnicity, they were sentenced to forcible eviction from their places of historical residence in the Karelo-Finnish SSR. Helling Khaikara, also a Finn and timber industry worker, lived in St. Shalakusha of the Nyandoma region. He was arrested 05/06/1944 and charged under Art. 58-10 h. 2 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR. He died in prison on 06/15/1944. Ksenia Karlovna (Yakku) Khaikara lived in the Murmansk region in the village of Belokamenka. Her minor children were Anersi Ivanovich Yakku, born in 1926, Armida Ivanovna Yakku and Karl Ivanovich Yakku, born in 1932. All were convicted by order of the NKVD of the USSR No. 00761 of 23.06.1940.

Two years ago, Agnes Haykara decided to create her family tree. There are 210 names on Agnes’ list. Of these, 10 are her relatives including Karl Haykara, a communist who joined the Communist Party with his sons and became a partisan during the war. This data is from the Murmansk archive of the regional committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The family tree has ended up being a martyrology.

Almost no one has written about the repressions against the Finnish population of Murmansk. There is a history of the deportation and executions of Finnish and Norwegian colonists by the Russian-Finnish writer Sven Lokko, who personally survived the repressions. Today, I am scrolling through the text of Agnes Haykara’s book about her family for the first time on a computer. The published paper version of the book is not available and has other readers now. On December 22, 2020, FSB officers confiscated all of the copies of Haykara’s work from the printing house. They only wanted the fresh copies.

The reason for the confiscation is the investigation of an alleged fraud. They say that the grant from the regional Ministry of Culture, who partially covered the costs of preparing the publication, was misused.

Grants were awarded to 10 authors, including Haykara. An independent jury studied the submitted manuscripts and gave Haykara the highest number of points. According to a Novaya Gazeta source, the grant was worth about a million rubles (11,000 Euro) and it was used almost entirely for the competition fund. The prize was divided amongst the winners and Haykara received less than 87 thousand for the book. This was enough to prepare a printing run.

The ministry’s budget money has absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the expenses and what is more, according to the terms of the grant, it is obligatory to honestly report all work done to the state the same day. But now even this is impossible to do because there are no longer any books. Even the printing house is surprised that the FSB only took Haykara’s book. They did not bother with the book by another author who was publishing under the same grant. They only wanted to stop Haykara’s.

If the FSB is claiming some kind of embezzlement, let me repeat that the printing house did not receive any budget money for it. So far they have managed to print only 25 copies, which is not the entire planned circulation. The rest were due to be reprinted on another day.

After making sure that they had taken everything, the FSB operatives drew up an act of voluntary extradition and left.

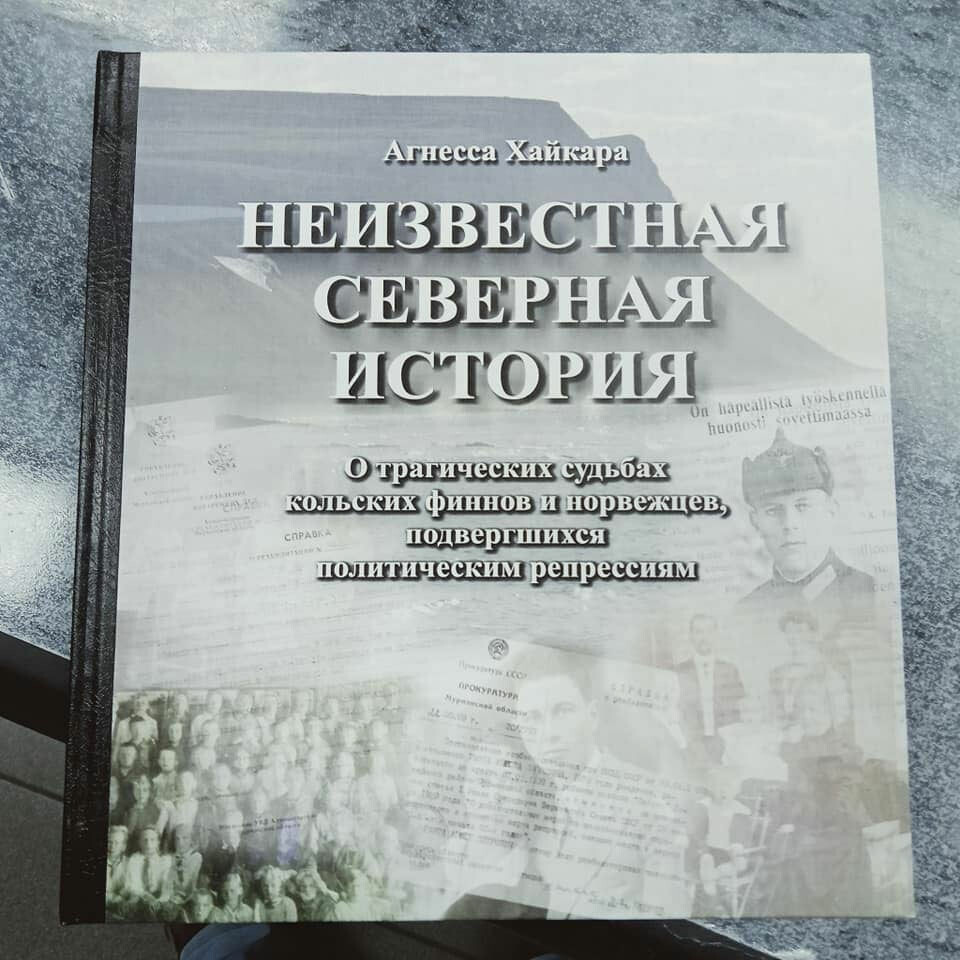

Agnessa Haykara defines the genre of “An Unknown Northern History: The tragic fate of the Kola Finns and Norwegians who were subjected to political repression” as a documentary story told through documents, testimonies and interviews and the story of her family runs through it as a thread.

Colonists appeared in the Kola Peninsula (Murman) in the middle of the 19th century when Alexander II opened the development of the region to foreigners. The deal exempted them from taxes, provided loans and timber for the construction of housing and ships and they were granted the right to free trade with Norway. The only condition was that the newcomers had to accept Russian citizenship.

Soon there was a lively trade with Norway, the colonies were developed and built and the Murmansk Territory became more and more populated, which was what the government wanted. By 1913, there were 3 thousand colonists living here and most of them were Finns. Haykara quotes one of these reviews and travelers to the colonies compared what they saw to Russian villages and their reviews were so enthusiastic, they sound like the Soviet people who first went to Scandinavia.

“There are no piles of shit lying near the houses and contaminating the air with stench. Everything is carefully collected and taken out to the pastures as fertilizer. And as a result, the barren desert has turned into beautiful grassy pastures and cattle breeding in the Finnish colonies is in a flourishing state in comparison with the Russians. There is also a noticeable desire for comfort in the houses. Almost everyone has books and even subscribes to newspapers though not the papers from Russia.”

Within a few years, these “non-Russian” newspapers would become material evidence in cases under Article 58.

In the 1920s, a Finnish newspaper was published in Murman called “The Polar Collectivist”. The paper wrote how shocking it was that the Finnish population “is moving towards a prosperous life and fulfilling the wise instructions of our great leader, Comrade Stalin.” The town of Polyarni, now the base of Northern Fleet submarines, was then the center of the national Finnish region. 100 years later, Murmansk FSB operatives would return to Polyarni to confiscate books about the indigenous Kola Finns who were subjected to political repression.

During the years of repression, people also came from Murmansk. The first colonist was convicted in 1930. His name was Henrik Berger and he was originally from Tsyp-Navolok on the Rybachy Peninsula. The charge was illegally going on a boat to visit his Norwegian relatives. They gave him 10 years and he disappeared on the White Sea canal. Then they took his friends and relatives. Then they uncovered a “Finnish spy cell” from among the Tsypnavolok people.

Until May 1938, they were taken to Leningrad to be shot. Murmansk was then part of the Leningrad region. Many Murmansk colonists, fishermen and lumberjacks lie in the Levashov training ground. After that, they began to practice “enforcement” right in Murmansk. Where exactly these executions took place as well as the place of the burials were classified until now.

Bureaucratically, It is only known that for the 60 people sentenced to imprisonment in 1936-1938 in the Murmansk region and there were 140 execution sentences.

The wives and children of the enemies of the people were not sent very far away to Khibinogorsk. Now it is the city of Kirovsk, where wealthy tourists are about to fly downhill on skiing vacations. Seventy years ago, the town was built on the bare tundra by prisoners and special settlers.

Nelly Heikkinen, was a prisoner of Khibinogorsk:

“Our “native Communist Party” took everything from me. They took my house, a motorcycle, tools, livestock and the personal belongings of all family members. They even took the children’s clothing, hoping that they would die in the Gulag. And most importantly, they took away and destroyed my parents and their traditions, our native Finnish language, culture and even our joy of existence. I have spent my entire life in fear.”

Johann Heikkinen refused to join the collective farm and fled to his homeland under the threat of arrest. But his homeland considered him a spy and after 14 years in prison, they extradited him back to the USSR under a peace treaty. His family including a pregnant wife and five minor children were thrown into the construction site of the Khibinogorsk mine. Nelly was born in a barrack. Johann was not shot however. He was accused of anti-Soviet agitation but died before the verdict on September 30, 1945. According to a statement from the prosecutor’s office, the official cause of death was a “cerebral hemorrhage.” The record of his burial place is marked as “not possible to establish.” By that time, his wife had died in the camp as well.

Nelly Heikkinen spent 13 years in an orphanage. She recalls that in the orphanage, they were called “Finnish dogs”, “Finnish bastards” and “enemies of the people”. Like many children of the Gulag, Nelly has been experiencing and re-experiencing its consequences her whole life. She lives with the loss of rights, a broken destiny and having no home and no homeland. She spent the 90’s having to make due on the meager benefits available for the repressed.

In 1994, she asked the President of Finland for citizenship. On one of the pages in Haykara’s book, she publishes Nelly Heikkinen’s letter written in neat handwriting:

“I don’t want to live in Russia because I don’t trust anyone. I earnestly ask the President of Finland to accept me into his state without any red tape since I don’t have a lot of money for paperwork.”

Nelly Heikkinen now lives in Tampere, Finland. Next year she will be 90.

It took over two years for Agnes Haykara to reconstruct the stories of the 210 repressed colonists.

Archival information was given to her by the Arkhangelsk, Murmansk, Karelian archives and the archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of these regions. She also found information in the church books of the Evangelical Lutheran parishes of the three border countries of the Barents region. More data was obtained from abroad than from Russian storage.

The memory of the Gulag is still “tremulously” guarded by the heirs of those who were arrested, tried and shot. Haykara never even found the certificate of “rehabilitation” of her own relatives. Her mother once received a response from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. It said that Hemming, Matilda, Fritj, Alina and Karl Haykara were designated as rehabilitated on June 13, 2018. The certificates of rehabilitation themselves were not issued. In order to obtain those documents, they say, it is necessary first to prove kinship in court. Protecting personal data is important and the state will look after the interests of the repressed themselves.

“Finland has recognized our kinship. My mother was repatriated on the basis of her documents but the Russian state does not recognize this relationship and demands that we go to court to prove it. Moreover, even the very fact of the death of our repressed relatives is required to be proved. Murmansk is 104 years old and my ancestors came to the Murmansk coast 150 years ago. And even 80 years after the repression, their memory is still banned. We must restore the good names of the innocent colonists who suffered.”

Since the book was seized, Haykara seems to be under arrest again. She really wants to get her book released.

“I didn’t write this book for myself, I wrote it for them and for their memory that they have been trying to erase for so long.”

Agnessa Haykara finds it difficult trying to find a logical explanation for the absurdity of what has happened to her publication. True, the information already exists. It’s right there in her book and is well formulated. So here is yet another example of someone’s tireless work and best efforts not to lag behind the others in exposing the crimes of our common enemies.

Translated from Russian by Adam Goodman