Former military camp turned into Arctic migrant center

Rajan from Nepal hopes to get permission to stay in Norway after bicycling across the border from Russia. Today, Europe’s northernmost refugee camp opened outside Kirkenes.

Rajan is happy with the bed he got after three days on travel from Moscow, across Russia’s snowy Kola Peninsula towards the border to Norway. He is one of the first to be transferred to Reception Center Finnmark that opened on Wednesday.

“I don’t have a home in Nepal. I am homeless and moved to Moscow to get a job,” Rajan tells.

“In Moscow, I stayed for three months. Then I saw on TV that Norway’s border was open. It took me three days to travel,” the young Nepalese man says.

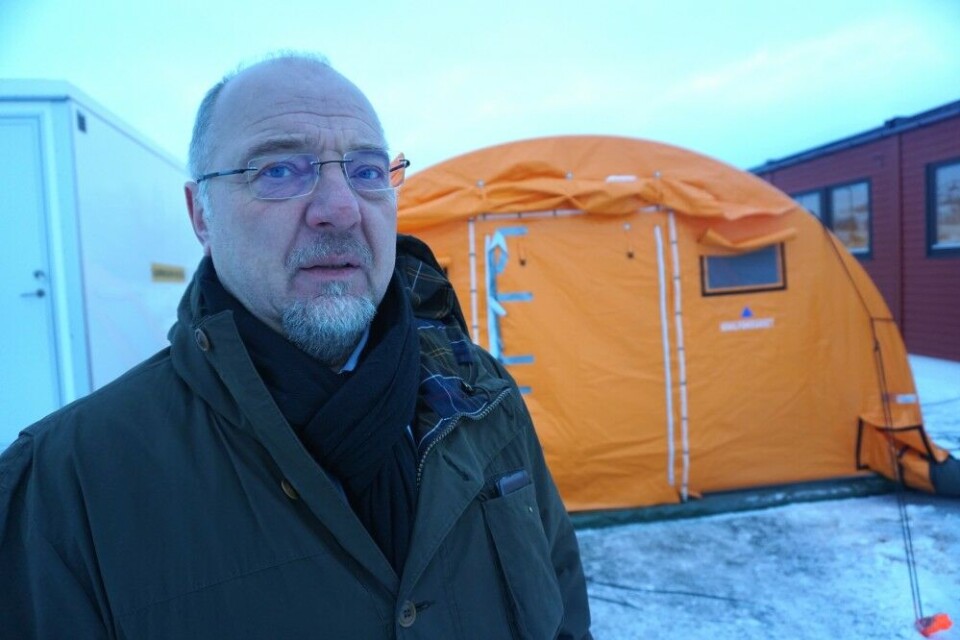

He is one of 300 migrants that have got a safe bed at the newly erected barracks at a former Home Guard camp next to the airport in Kirkenes. Officially opened by State Secretary Jøran Kallmyr in the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Kallmyr gives little hope to many of the newly arrived migrants.

“It is obvious that many of those arriving from Russia nowadays don’t have a need for protection and therefor don’t have the right of asylum,” Jøran Kallmyr says.

“Our first priority now is to get them a roof. It is an extremely demanding situation and the staff works round-the-clock.”

Syrian refugees first discovered the Arctic Route into Western Europe in August. Since then, more than 4,000 asylum seekers from more than 20 countries have entered at Storskog, Norway’s only checkpoint along the 196 kilometers long joint border with Russia.

Limited capacity at the border forced police in charge of migration control to put up tents and barracks. Refugees had to line up outdoors awaiting registration. Not a pleasant situation as the winter came last week with freezing winds and temperatures dropping down to minus 12°C.

Built to give a bed for up to 600 asylum seekers, the new arrival center has all basic infrastructure. From entrance, the migrants walk through rooms for dressing, fingerprints, ID-check, first registration and interview. Everything in separate rooms. Both the local municipality and staff from Kirkenes hospital provide health care services. Finally, a bed-number is given together with a chip-card to the dining room. Kids have their own play-corner. Unaccompanied minors have their own house.

“Standard is simple, but safe,” explains Lars Egil Sørsdal, coordinator for the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration at the center.

He shows us the waiting room, where TV-screens on the wall provide information about how the registration procedures are organized. The text is changing from Arabic, Russian, English and several other languages.

“It saves us big costs for translators,” Lars Egil Sørsdal explains.

Nobody has any overview of how much the current wave of immigration will cost Norway. Two weeks ago, the Government added another 9,5 billion kroner (€1 billion) to its 2016 budget. Since then, the inflow of asylum seekers has continued to rise. So far, more than 20,000 migrants have asked for asylum in Norway. The numbers are likely to be closer to 35,000 by year-end.

“20,000 asylum seekers from August until now creates huge challenges for Norway. Many of them arrived at an unexpected place,” says State Secretary Jøran Kallmyr.

Kirkenes is as far north from Oslo as Rome is to the south. At 69°N, the border checkpoint between Norway and Russia was not on any European politicians’ map when discussing the refugee-crisis some few months ago.

“I feared we could get an “Arctic Lampedusa” when the winter came,” Kirkenes mayor Rune Rafaelsen says. Last week, he met his colleague in the Russian border town of Nikel. A town where the local hotel has been filled to over capacity with nationalities from the Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa. All waiting for the ride over to Norway.

Cross-border cooperation in this region has developed rapidly in the years after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Businesses, cultural exchange, joint marriages, political contacts and a wide-range of people-to-people projects across the border have developed an atmosphere of low-tension between the northern regions of Norway and Russia.

For Rune Rafaelsen, the job is to keep alive these ties and friendships. Also in a time when the huge migrants flow into Europe has discovered the northernmost door.

“I am very proud of the people in Kirkenes who stay calm in this though situation,” Rafaelsen says.

“All over Europe we see anti-migrant protests in the streets. Refugee centers are put on fire. In Kirkenes, we have not seen one single anti-migrant poster. I admire the locals for their ability to help the refugees arriving in such circumstances,” Rune Rafaelsen says.

People in Kirkenes have their history in mind when giving a helping hand in the current refugee crisis. In 1944, German forces burned down most houses in Finnmark. Adolf Hitler ordered some 50,000 people to leave in boats, buses and trucks. Some went to Sweden, others to southern Norway.

At the reception center opened on Wednesday, few know about the war in Finnmark 70 years ago. With mobile phones, some try to connect to family and friends at home. Those from Syria and northern Iraq are worried about their beloved ones still staying in areas with wars and ISIS terror.

But far from all entering Western Europe via the Russian Arctic Route are fleeing from war. There are only a few Syrians among the 300 asylum seekers at the camp in Kirkenes.

“Now, we will speed up the handling of the applications and arrange for a speedy return for those not in need for protection,” says Jøran Kallmyr.

On Sunday, Norway’s Prime Minister Erna Solberg will visit the new camp. Europe’s migration crisis has become big politics, also in Norway.