End comes to 100 years of Norwegian coal mining at Svalbard

Amid a boost in the geopolitical and strategic importance of the Arctic archipelago, the Norwegian government makes clear that the once so powerful industry must end.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 14.0px; font: 12.0px Times; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 14.0px; font: 12.0px Times; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 14.0px}p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p4 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}p.p5 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 15.0px; font: 12.8px Arial; color: #222222; -webkit-text-stroke: #222222; background-color: #ffffff}p.p6 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 15.0px; font: 12.8px Arial; color: #222222; -webkit-text-stroke: #222222; background-color: #ffffff; min-height: 15.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

The cabinet of Prime Minister Erna Solberg explicitly says it no longer wants to subsidise the digging out of black rock from the Spitsbergen mountains.

In the fiscal budget presented by the government today, the mines of Svea and Lunchefjell are proposed closed and abandoned and a cleanup of the surrounding areas initiated.

Only Mine No 7, a smaller deposit, is to be kept in operation in order to provide supplies to the local coal-fuelled power plant.

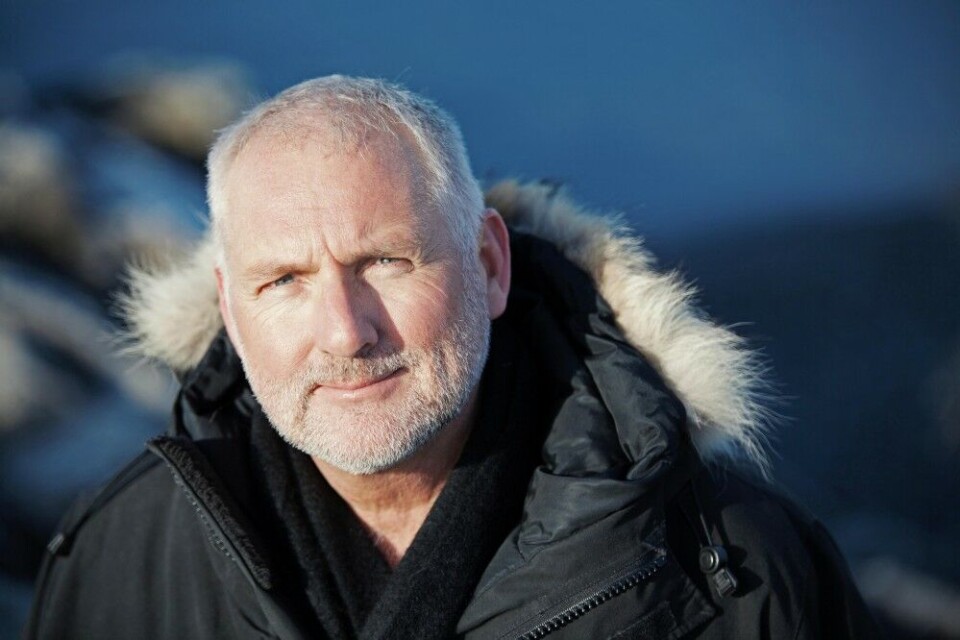

«This is the end of a more than 100 years long era of coal mining in Svalbard», says writer and Svalbard analyst Per Arne Totland. He believes economic concerns is the main reason why the mines are being closed.

Over many years, Norway has pumped millions of kroner into the Svalbard coal industry. And the economic troubles of state mining company SNSK have mounted following lower coal prices.

The company report from Q2 this year states that there is available financing only until the end of 2017 and that further company activities will depend on external investments.

New industries

The closure of the Svalbard mining industry comes as no surprise. A government white paper on the archipelago from 2016 announced a mining moratorium on extraction from the Svea and Lunchefjell mines and underlined that “there is significant uncertainty connected with a restart of the mining”.

Other industries were highlighted and presented as replacement, first of all tourism, research and higher education.

Comeback for geopolitics

However, it is a paradox, Per Arne Totland argues, that the mining is being shut down in a period when the international pressure against Norway’s Svalbard policy is increasing from several angles.

The coal mining has been the key industry at Svalbard ever since Norway won sovereignty over the archipelago in 1920. And the miners have been of great geopolitical importance for Norway as a means for maintaining business and settlement in the area.

«The SNSK has until now been one of the most important tools in the Norwegian toolbox on Svalbard, and what the government now actually is doing is to put this tool aside,» Totland says.

«It is replacing its sledgehammer with a small set of tongs.»

Furthermore, Totland argues, it might be more expensive for Norway to close the mines than to keep them open. The closure and cleanup of the mines is estimated to cost up to 1 billion kroner, while it can not be excluded that the Svea and Lunckefjell mines would actually have been able to make money.

«And the re-opening of mining would have given 200 new jobs over the next 12 years, which is significant for the small economy of Svalbard,» the analyst says to the Barents Observer.

«And it would have given us time to restructure the society», he adds.

The role of Russia

Svalbard is a sovereign part of Norway and managed by Norwegian legislation. At the same time, the Svalbard Treaty from 1920 gives other signatory states the right to engage in exploitation of local natural resources.

When the Norwegian mining company closes and abandons its mines, other companies could potentially move in and take over the activities.

There are obligations connected with the mining acreage and licenses, and these could potentially be taken over by other stakeholders, says Per Arne Totland.

«Mining companies from other signatory countries can raise demands for the licenses and start up mining in the former of SNSK», he warns.

«And these companies might be subsidised by their national government and consequently not be dependent of commercial interests».

Russia has for decades been strongly represented in Svalbard. A total of 570 people now live in the settlement of Barentsburg and the Russian company Arktikugol has since the early 1930s extracted coal on the archipelago.

Militarization

The Norwegian government Svalbard budget is presented as military presence in Arctic waters is on the increase along with a consequent growth in the strategic role of the archipelago.

Over the last years, Russia has built up a major new and upgraded military base at the nearby archipelago of Franz Josef Land. This base includes a 14,000 square meters military complex with living and working conditions for up to 150 soldiers, as well as air field built for fighter jets.

A 2016 report from the Russian Ministry of Defence, made available to the public last week, says the Norway’s Svalbard policies raises the «potential risk of war». Norwegian authorities are seeking to establish «absolute national jurisdiction over the Spitsbergen [Svalbard] archipelago and the adjacent 200 nautical miles maritime boundary around», the report writes and accuses the country of unilateral revision of international agreements.