Retreating sea ice in Arctic affecting zooplankton behaviour

Scientists studying Arctic sea-ice retreat have discovered surprising impacts on microscopic aquatic organisms, suggesting potential ecosystem changes in the coming decades.

“Particularly when it comes to the topmost 20 metres of the water column, just below the sea ice, there was no available data on the zooplankton,” Hauke Flores, a researcher from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI),said in a statement.

“But it’s precisely this hard-to-reach area that’s most interesting, because it’s in, and just below, the ice where the microalgae that the zooplankton feed on grow.”

Seasonal migrations in Arctic

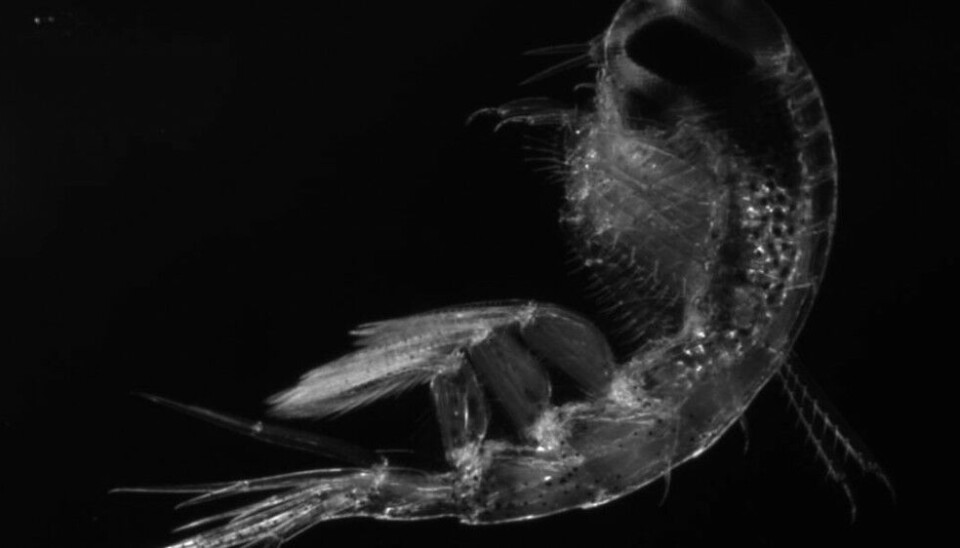

To do the study researchers looked at zooplankton, made up of codepods and krill.

At night, the organisms rise to the ocean’s surface to feed and retreat to deeper waters during the day to avoid predators.

But zooplankton in the Arctic are different – they follow the seasons.

There, they stay deep in the ocean all summer, when the sun doesn’t set in the Arctic . Then during the polar winter, when the sun doesn’t rise, part of the zooplankton stay at the top of the ocean just under the ice.

But as the climate warms and Arctic sea ice retreats and gets thinner, more light is getting through.

“Since marine zooplankton respond to the available light, this is also changing their behaviour – especially how the tiny organisms rise and fall within the water column,” the AWI said in a news release on their website.

“The tiny organisms usually prefer twilight conditions. They like to stay below a certain light intensity (critical irradiance), which is usually quite low and lies well into the twilight range. When the intensity of sunlight changes in the course of a day or the seasons, the zooplankton go where they can find their preferred light conditions, which ultimately means they rise or sink in the water column.

To better understand the relationship between the organism’s behaviour and light conditions, the researchers constructed an autonomous biophysical observatory, deploying it beneath the ice at the conclusion of the MOSAiC expedition.

The area of the Arctic examined was in 2020 near the North Pole during the autumn-winter period and then towards the North of Greenland in the winter-spring period.

They then fed that data into a computer model along with different climate scenarios. They found that the warmer it got, the more time the organisms stayed at deep depths, and the less time then spent near the surface, something that would have a domino affect on other parts of the arctic ecosystem.

“In warmer future climates, the ice will form later in the autumn, resulting in reduced ice-algae production,” Flores said.

“This, in combination with their delayed rise to the surface, could lead to more frequent food shortages for the zooplankton in winter. At the same time, if the zooplankton rise earlier in the spring, it could endanger the larvae of ecologically important zooplankton species living at deeper levels, more of which could then be eaten by the adults.”

Flores said the ecosystem impacts would decrease as the international community gets closer to the 1.5-degree Paris climate agreement targets.

“Altogether, our study points to a previously overlooked mechanism that could further reduce Arctic zooplankton’s chances of survival in the near future,” Flores said.

“If that comes to pass, it will have fatal consequences for the entire ecosystem, including seals, whales and polar bears. But our simulations also show that the impact on vertical migration will be much less pronounced if the 1.5-degree target can be reached than if greenhouse-gas emissions rise unchecked. Accordingly, every tenth of a degree of anthropogenic warming that can be avoided is critical for the Arctic ecosystem.”

This story is posted on The Barents Observer as part of Eye on the Arctic, a collaborative partnership between public and private circumpolar media organizations.