Draft agreement ready for the ministers

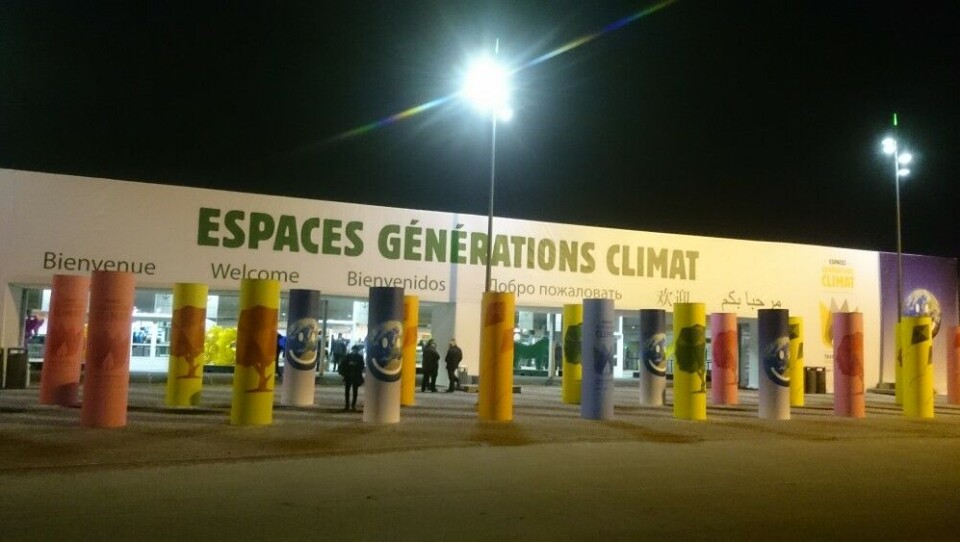

PARIS. After close to one week of negotiations at the climate conference (COP21) in Paris, a draft agreement is on the table.

The draft is put forward for discussion among the ministers on Monday, the climate negotiators say.

The original text of 51 pages has been shortened to 48 pages by the negotiating parties and yesterday the co-facilitators also published a 38-pages long bridging proposal which seeks to provide compromises on the conflicting elements of the agreement. The new draft has just over 900 brackets compared to 1500 in the original text suggesting that some consensus has been reached during the past week, although much remains to be done.

Kelly Dent from Oxfam sees clear improvements when asked how the ongoing negotiations compare to the unsuccessful Copenhagen conference in 2009. “We’ve got a 38-page text, which is not bad”, she says, comparing the draft agreement to the 200 pages that were presented to the ministers in Copenhagen seven years earlier.

“We have definitely seen more momentum”, says Dent. “The atmosphere has turned fairly brutal”, she notes, pointing to that a lot of diverging political positions are put forward resulting in both confrontations and trade-offs between the negotiating parties.

Also Sven Harmeling from CARE International sees positive development in the negotiations. “I think we are better off”, he says, noting that the conditions are also more favourable this time as the institutional framework is better now, with important elements such as the Climate Fund already set up.

“Loss and damages is an improvement” says Harmeling, referring to the mechanism which is meant address the adverse effects of climate change. In the bridging proposal, the already established Warsaw International Mechanism is at the centre of loss and damages and the new text also addresses displacement resulting from climate change, which is an important issue for many developing countries. This is also put forward by Sangdeep Chamling Rai from WWF, as one of the achievements of the negotiation. He notes that prior to the conference, developed countries wanted to exclude loss and damages from the treaty but now, after one week of negotiations, there is consensus about its inclusion in the text.

While there are positive developments, there are still many challenges left before a feasible agreement can be achieved.

Funding remains an infected issue and so far there is little progress. “Finance needs to be on the table now”, says Dent. “It’s too important for it not to.” There is currently a significant finance gap for adaptation measures. Today, the international public finance for adaptation amounts to US$ 25 billion, whereas the annual cost will range between US$ 140-300 billion by 2030, according to a new report by UNEP. The original negotiation text stipulated that the financial instruments should allocate equal amounts of funding to mitigation and adaptation respectively, however this clause has now been removed in the new draft, making it even more important to establish funds for adaptation. “We really need to see rich countries doing more” says Dent, pointing out that developing countries will not commit to anything until they are certain to get financial support for the transition to a more sustainable society. However, the developed countries have not yet provided a clear plan for how to deliver funds and financial contributions are lacking.

There is also work to be done on equity. According to Brandon Wu from Action Aid, the current divide between developed and developing countries is no longer acceptable to developed states and at the same time developing countries are not prepared to commit to an agreement with equal treatment of all states. “We need a third way”, he says, suggesting one which is based on a set of indicators, such as historic responsibility and capacity, which would determine the country’s contribution. “Only with that kind of system can we get to an outcome that has all parties on board, with an agreement that is actually strong and ambitious and has a hope of achieving a 1.5 long-term goal”, says Wu.

The ultimate level at which the temperature must be stabilized is also an issue which lacks consensus. Both France and Germany have supported the temperature limit of 1.5 degrees during the negotiations. However, the Arab Group, led by Saudia Arabia, has blocked any alternatives suggesting a longterm goal of lower than 2 degrees warming.