Removed from the granite

In the Murmansk region, fallen soldiers of the Great Patriotic War have just had their gravestones taken away

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 10.7px 0.0px; line-height: 20.0px; font: 16.0px ‘Times New Roman’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 14.0px; font: 12.0px Times; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 14.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}span.s2 {font: 12.0px Times; font-kerning: none}

By Tatyana Britskaya

We stand among the tombstones with Konstantin Dobrovolsky, the chairman of the Murmansk search unit coordination council. «Here we have Archontov. We managed to find his relatives and they have come to the grave. Over here lies Selinsky and Peshkov, the latter having died as a 22-year-old battalion commander. The places where the soldiers were cut down are marked with cut granite stones. Dobrovolsky’s people go searching for the remains of the soldiers of the Great Patriotic War every summer. This fall, 48 newly discovered people will be marked and buried. In total, 7 thousand people are buried at the memorial cemetery in the Valley of Glory, 75 km from Murmansk. All of them have been found because Dobrovolsky’s people have looked for them.

They have been burying remains for 35 years in a place better known as Death Valley by surviving soldiers. The cemetery commemorates the boys who, dressed only in summer uniforms and freezing in the rocky hills, held this land for 4 years. Everything here on the bank of the Zapadnaya Litza river is saturated with death. Even the birds do not sing. People come here to cry.

But because the cemetery expands every year and there is simply nowhere to bury people any more, they have started a second reconstruction project on the memorial. The plan is to add two more sectors to the six that are already full and to put the places already marked in order. This plan includes graves that were dug in the autumn at the end of the search season when the earth was already frozen. These places and the tombstones tend to sink a bit and often almost disappear.

However, when Dobrovolsky agreed to the reconstruction project, for which the regional budget would pay 20 million (about €260.000), he did not suspect that the fighters’ names would be removed from the stones. Those stones until now have marked the final resting places of those men whose names he and his people have painstakingly established, by restoring medals and other artifacts and digging in the archives. And in place of the old tombstones, new concrete foundations have been installed or specifically arranged let’s say, so that their appearance is more accurate and symmetrical and therefore perhaps, more beautiful. But most importantly to Dobrovolsky, the stones no longer mark where the soldiers fell and where their remains actually rest.

Three neatly placed foundations in the lawn now mark the spot at the end of the sector where young commander Peshkov lies. After more than a decade of search work, Dobrovolsky remembers by heart where each of the 7 thousand men lie. Without checking the papers, he solemnly points out that eight people are actually buried here and that five of their stones have been lost. On the other side of the sector, the gravestones are becoming larger and 20 single cement pedestals are firmly planted in the ground there at the site of three mass graves where one and a half thousand people lie.

Dobrovolsky is indignant. «I talked to the director of the local historical museum and she told me the idea was to make the park more beautiful. I told her she could beautify a park or a kitchen but she should leave the truth alone here.»

In the autumn, Murmansk regional historian Mikhail Oresheta came to the Valley of Glory and was horrified. Oresheta is known for once following a search out to the national scale. He immediately sounded the alarm on social networks. «Imagine that you come to the cemetery to visit the grave of a person close to you and suddenly find another name on the tombstone. And then you find that the memorable sign you set with your own hands now stands on a completely different hill. This is what relatives of the warriors at rest in the Valley of Glory will find here if they come after the reconstruction. With the stroke of some bureaucrat’s pen, the tiny personal gravestone marked on single and mass graves were simply erased. Sure, now the grave sectors are in perfect shape. It is very good! It’s just very bad that the new and more attractive pyramids were not set on the specific graves where the people are buried. Why have they moved the markers to completely different places?”

Oresheta’s complaint got shouted down in a boorish manner by a government newspaper. His message referring to the regional cultural committee was called fake news, an inappropriate and cynical joke and they accused him of “dancing on the bones.” The paper made its point that the new scheme would be to place the tombstones as close as possible to the specific burial sites of the individual soldiers and that the previous burials were not systematized. And they added that the new project was coordinated and done under the supervision of the curators.

And Dobrovolsky agrees that indeed, there had been a meeting. «We were asked whether to put tombstones in straight lines or in a checkerboard pattern. But no one said that their locations would change or that the markers would be carried away from the graves.»

While we are walking in the Valley of Glory, the museum calls Dobrovolsky, asking yet again what complaints he has about the reconstruction. He slowly repeats: «It was never important for the place to be beautiful. It was important to be simply what it was.» And with that, the conversation ends.

Later that evening, Elena Himchuk, the museum director, promises Mikhail Oresheta to make adjustments to the work that has already been done. They are willing to replace the markers with the list of prisoners of the Norwegian “Nautsi” camp buried in one of the sectors and restore the tombstones on 10 single graves in the front side of the first sector. Other than this, the officials insist that they have done everything else correctly.

However, these are very similar words to how they described their “optimization” project 10 years ago. And everything then was fine unless you count the contribution of the military enlistment office. Their reconstruction of the memorial to those who died in the Arctic managed to lose a thousand names that had previously been immortalized there on a granite wall. A thousand names wiped away. A whole battalion lost yet again.

Maybe the officials here are truly moved by their passion for optimization. Who knows. Why have they created a problem out of the blue that neither the curators, local historians, or journalists understand. Adding to the negative emotions were the drone images published on the Internet at the beginning of the reconstruction. These pictures showed how carelessly wreaths had been taken from the graves and tossed into a heap in the forest. They also showed how the graves themselves were empty gaping holes for some reason. People who had ordered stones were outraged. Obviously, they were not carrying out reburials although doing so was one of the original points of the plan.

The fighters lying here could not find peace for more than 70 years. Nobody spoke about them and it was forbidden to search for them. “Nobody is forgotten!” became an empty and false claim. The men had been deprived of their names and destinies and now, even after their long awaited funerals, they must suffer yet another outrage.

We next search the Valley for the tomb of Captain Ageychev. «I once helped some of his relatives find other relatives. He was not buried for such a long time because there was no money. And then there was no money for a granite monument so, Captain Ageichev lay beneath a peeling wooden pyramid. Now look. There is nothing in the place where his coffin lies. On the right and on the left are two future tombstones. But there is nothing now marking his grave.»

Dobrovolsky also worries that the portraits of the fighters will disappear from the tombstones. Relatives have always brought their own granite slabs and installed them themselves. True, this did not keep with the uniformity but it is unclear who should be bothered by this.

«They tell me that the monuments were placed in an ugly and asymmetrically manor. None of them died symmetrically.»

Dobrovolsky shows me the photos from which the portraits were made asking me to look into their eyes. «Here Melnikov lies. He is here in the place where he died. And he himself was from Belarus. I went there and asked his people what he was like. When we found him, there was a note with him. It said ‘Please inform Lena’. And at his house, I saw a photo of him wearing a white shirt. His hand was on the shoulder of a girl sitting in a white dress. Lena, I suppose. He lies here in this sector.»

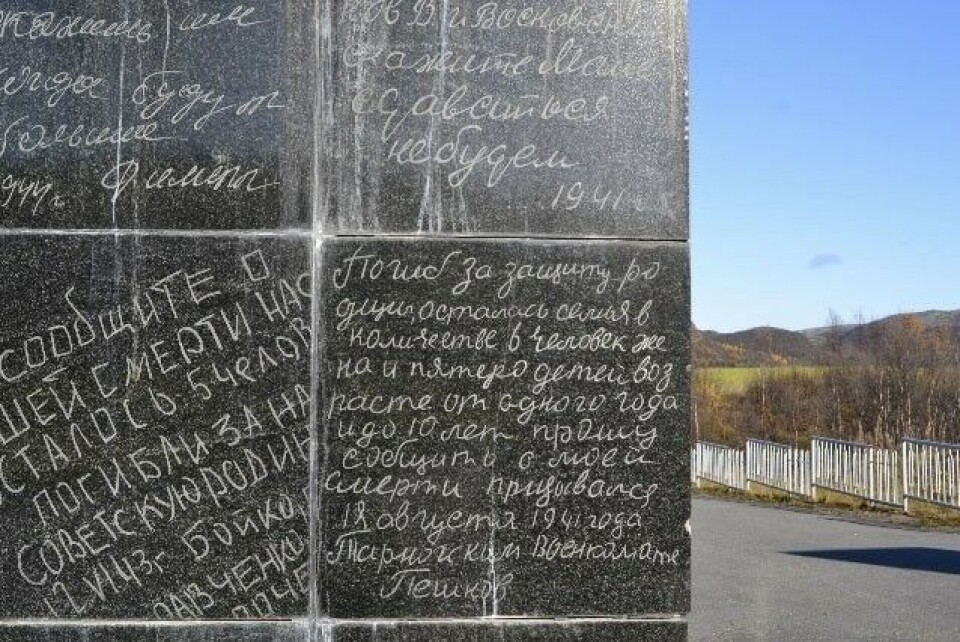

Dobrovolsky shows a photo from when some older children first came to visit the graves of their fathers. «They got down on their knees here and kissed the names on the plates. The daughter of the battalion commander, Peshkov, told me that her father had been taken away from the village in a cart. And at one moment, he looked around» and thus he remained so before her eyes. And here where we stood, she saw his suicide note etched into the granite.

These notes, extracted from artifacts found with the dead, cannot be read with a calm heart. They speak much more than the solemn speeches that will soon be heard here again. On October 6, there will be another burial in the Valley of Glory. And next year will be the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Arctic. And there, when the grandchildren and children of the fallen arrive in the Valley, they will no longer find the names of those dear to them written on the granite.

This story is originally posted by the Novaya Gazeta and re-published as part of Eyes on Barents, a collaborative partnership between news organizations and bloggers in the Barents region