Only sealskin from Greenland can be traded in Finland. “The ancient tradition may disappear," says Finnish seal hunter

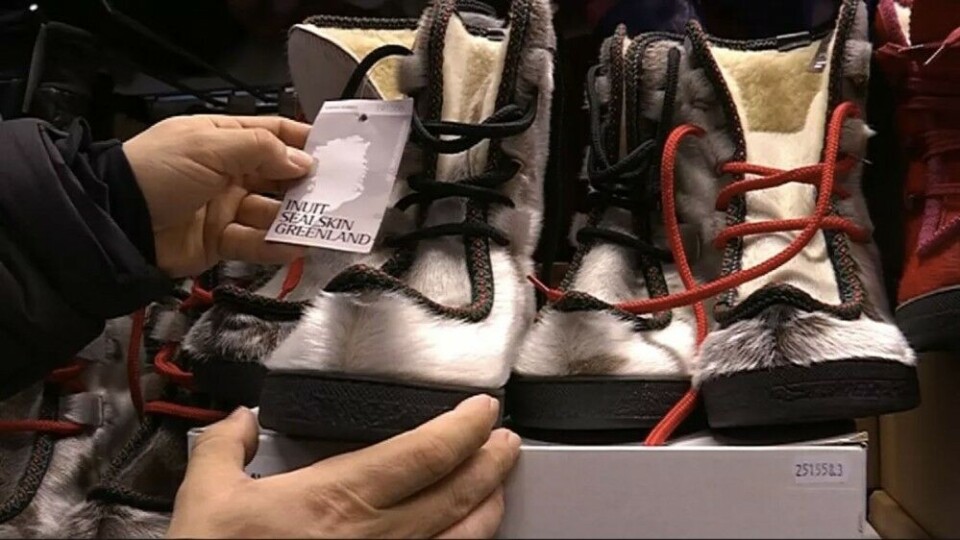

The warm sealskin products are easy to sell in the cold conditions of the Arctic. The material would also be available in Finland, but, because of an EU ban against seal trade, only sealskin from Greenland can be traded.

Text by Aslak Paltto, Susanna Guttorm and Linnea Rasmus

As winter embraces the north and cold spells hit the region, vendor Pekka Halonen starts his mobile shop and sets off to travel around Sápmi, the Land of the Sámi, in Finland and Norway.

The inhabitants of the north are used to good seal fur hats and appreciate them. Already for twenty years, Halonen has toured the north, selling a variety of goods, but sealskin products have always been his best-selling products.

“If we look at reindeer herders, the seal fur hat is the hat that almost everyone wears at work. And the same applies to seal fur mittens and boots.”

Halonen imports the material for sealskin garments, and the skins come from Greenland though seals are also hunted in Finland.

“Unfortunately, this is not made from Finnish sealskin. The skins come from Greenland to Denmark to be sold there. It’s a bit absurd that we’d have the material available here in the nearby waters, but we can’t make commercial use of it.”

Background: The EU forbade Finland from selling sealskin in 2015

In 2009, the European Parliament decided that seal products could not be sold in or imported for sale into the European Union.

There were two exemptions from this ban, and one of them applied to Finland. Pursuant to it, seal products that came from seals hunted for the sole purpose of the sustainable development of marine resources could be traded in the Finnish market. Such products could be sold, but with no profit.

The second exemption applied to the Inuit, the indigenous people of Greenland. The EU trade ban does not apply to products that have their origin in the traditional seal hunt of indigenous communities.

In 2015, the European Parliament revoked one of the exemptions. The Parliament decided to forbid the trade of products that come from small-scale seal culling for the protection of fish stocks.

The number of seals goes up in Finland, but with no benefit to seal hunters

Finland has a long tradition of hunting marine seals and making use of the catch. In the 1900s, seals were hunted freely. Because of a sharp drop in the seal stocks, seals were protected in the early 1980s. For the most part, the populations decreased because of reproduction problems caused by environmental toxins and excessive hunting.

For sixteen years, seal hunting was completely forbidden in Finland. Hunting was restarted in 1998, because seals were doing damage to fishery. However, hunting was strictly regulated at this point. According to the Finnish Wildlife Agency, most of the seals hunted at present are gray seals, with 300–500 individuals hunted annually in Continental Finland.

Both the Wildlife Agency and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry are of the opinion that the number of seals is, at present, so high that they could be hunted. In the territory of Finland, the gray seal population has multiplied since the early 2000s. In countings, about 10,000 individuals were observed in the early 2000s and as many as 30,000 in the 2016 countings. According to the evaluations of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the number of seals may be as high as 54,000.

Jouni Heinikoski from Kemi has been fishing and hunting seals for a long time in the Bay of Bothnia. His experience is that the number of seals increases every year.

“The truth is that the gray seal population grows approximately ten percent each year, so, mathematically, it doubles every 5–6 years. That’s exactly what has happened,” Heinikoski says.

According to Heinikoski, it is not profitable to hunt the gray seal, as you cannot sell the catch.

“The fact is that there’s a ban on their sale, so you can’t benefit from the hunt commercially. You can just give these away as a gift. You can’t trade them to anything, and you can’t take any money for them,” Heinikoski says as he shows his seal products.

Heinikoski is concerned about the tradition of seal hunting dying, because you cannot make economic use of the hunt.

“Unfortunately, it seems that the whole ancient tradition may disappear, under the circumstances. It’s difficult to imagine what would get people to hunt for the seal. If you don’t benefit from the hunt in terms of money, the hunting trip in the spring will just be an economic sacrifice,” Heinikoski explains.

The trade ban stays despite the growing seal populations

The officials of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry are aware of how frustrated fishermen and seal hunters are at the situation. According to Heikki Lehtinen from the Ministry’s Natural Resources Institute Finland (LUKE), there will be no changes in the EU trade ban on seal products. For a long time, Lehtinen has participated in the preparation of the EU seal legislation as Finland’s representative.

“It’s definitely not easy, if even possible, to imagine a situation and circumstances in which the Commission would start to revise the present legislation to fit our views.”

The demand for seal products increases – the import of sealskin decreases

The import of sealskin into Finland has been limited by an EU seal regulation, which restricts the import of all seal-based products into the European Union. Only a few companies operating in Greenland and Canada have the right to export sealskins for sale to the EU.

The decrease in the sealskin available in the market now forces Finnish enterprises to reflect on how to make the supply of sealskin correspond to its demand. Therefore, the manifacturers of garments now have to look for substitute products for the customers who would like to buy seal fur hats. Pekka Halonen has not yet come up with a substitute for sealskin.

“Well, I wonder what it could be. It might well be impossible to find one,” Halonen says.

This story is originally posted at Yle Sapmi and re-published as part of Eyes on Barents, a collaborative partnership between news organizations and bloggers in the Barents region.