What does it mean to live on a mountain of uranium?

Orrefjell mountain, in Salangen valley, Northern Norway, has one of Norway’s largest uranium deposits. The area is used for recreation and as pastureland for rough grazing animals, and the catchment area to the south is settled, with farms and houses. What does it mean to live on a mountain of uranium?

The main purpose of the research project Case Orrefjell was to investigate the implications of living in and using an area with elevated levels of radiation. The project was a cooperation between natural and social scientists with a broad scope covering studies of local geology, environmental transfer of radioactive substances, human exposure to radon, and the risk perception of people living in the area. Local residents were strongly involved by measuring radon in their houses and answering a questionnaire. A class of first-year students from the local high school assisted with the fieldwork, local involvement and outreach of the project.

Geology and environmental transfer to biota

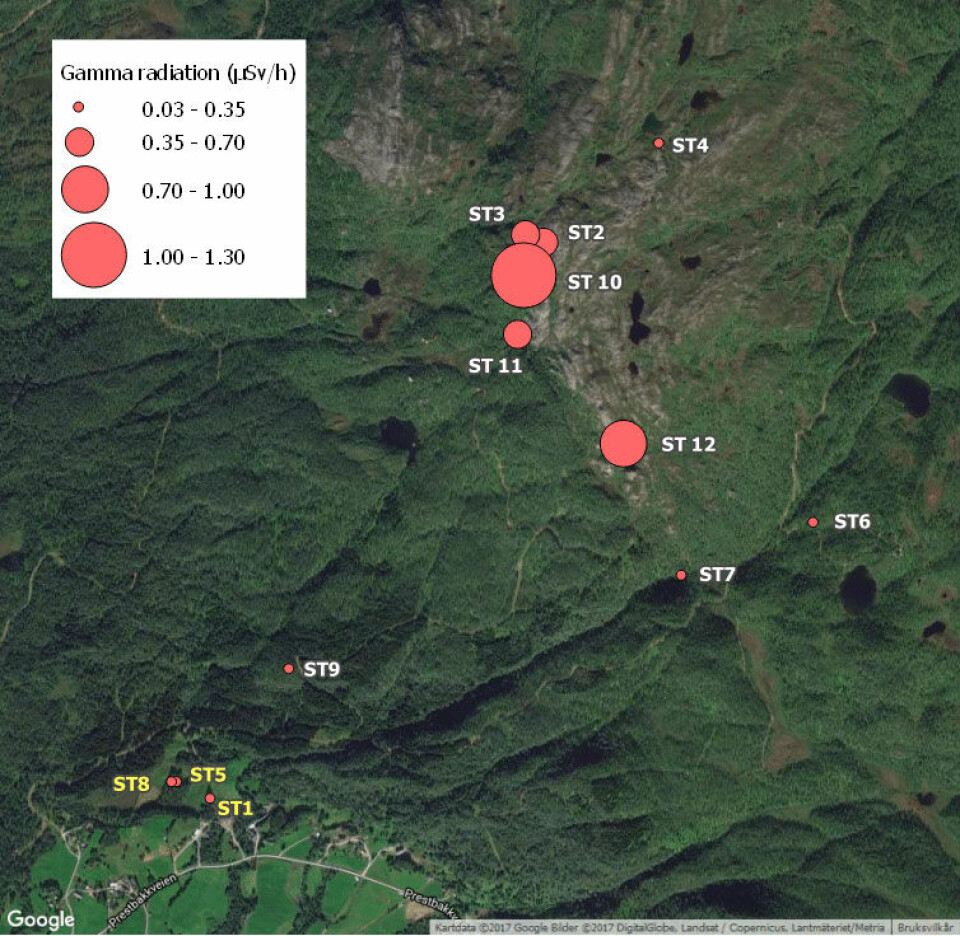

The uranium deposit at Orrefjell was first discovered in the late 1950s by Henry Lund from Salangen and further documented by Geological Survey of Norway over the decades that followed. The geologists involved in Case Orrefjell provided a baseline evaluation of the geology in the area, adding to existing knowledge. The biologists and environmental chemists used this information to locate sampling sites with a gradient of background radiation. To evaluate the transfer of radionuclides from soil to plants, both were sampled at each site. The collected plant species are either important for grazing animals or berries picked for human consumption.

Generally, the uptake of radionuclides in biota varied with the concentration of the radionuclides in the soil, as shown by uptake of radium-226 (a daughter nuclide of uranium) in bilberry heath and berries. Interestingly, the heath accumulated higher concentrations than the berries. There are no indications that the elevated background radiation or consumption of local products poses any major risk to those who use the area.

Radon

Another of the daughter nuclides of uranium is radon, a noble gas known to increase the risk of lung cancer. Norwegian authorities set a limit of radon in houses to 200 Bq/m3 above which homeowners are advised to implement mitigating measures to lower the radon concentrations as much as possible, preferably to below 100 Bq/m3. The physicists in the project suspected that the uranium at Orrefjell could influence the radon concentrations in nearby houses, so we asked all households in Øvre Salangen to measure residential radon during the winter 2016/17.

In some places, 20-30% of the households exceeded the recommended upper limit of 200 Bq/m3 in Øvre Salangen. Nationally, less than 10% of houses have radon concentrations above 200 Bq/m3, and the percentage of such houses is clearly higher in Øvre Salangen and highest close to Orrefjell itself. However, large variation in radon concentrations in neighbouring homes is common and may be due to the local variation of radon in the ground, building constructions, airtightness towards the ground and habits of aeration and heating. Everyone should, therefore, measure the radon concentrations in their own home.

The physicists and the geologists in Case Orrefjell are also working together to develop and improve the national susceptibility map for radon. The data from Case Orrefjell will be used in this process.

Risk perception among inhabitants

The social scientist conducted a survey of inhabitants’ awareness of risk from radiation in general and from radon exposure specifically. About 200 respondents completed the survey, of whom 71% live in Salangen. Of the respondents living in Salangen, 70% were aware of the elevated uranium levels in Orrefjell, but also replied that this did not affect their use of the area.

The greatest radiation risk to human health in the Orrefjell area is the exposure to indoor radon and most respondents were aware of this health risk. They also knew that the Norwegian authorities recommend all households to measure radon levels, but only one in five had acted accordingly and performed measurements. Some had found elevated radon levels in their houses, but very few had taken steps to mitigate the danger. This aligns with their apparent complacency about being exposed to radon, and their lack of perceived risk in their living and working environments.

Only 10% could recall having received information about radon from the local authorities and 80% of respondents welcomed more – and more easily accessible – information on local radon. We, therefore, provided the municipality with basic information about radon for distribution.

Different trails to the summit – a common view

By connecting scientists from various fields, and actively involving local residents, we approached Orrefjell from different angles. As researchers, we all learned something beyond our own discipline. In addition to strengthening the specific knowledge about Orrefjell and radiation exposure routes for humans and animals, the project provided insight into how information is received by the public, which in turn is a valuable input to authorities on how to adjust and improve communication.