A tale of a local fjord – investigating a marine system in our backyard

A cold wind gust hits our small aluminium boat, and we crash into another rolling wave. Spray splashes up but, for once, the cold, salty drops are welcome. Everyone in the fieldwork team is sweaty and breathless but very much alive. That was a close call, but we made it!

1.

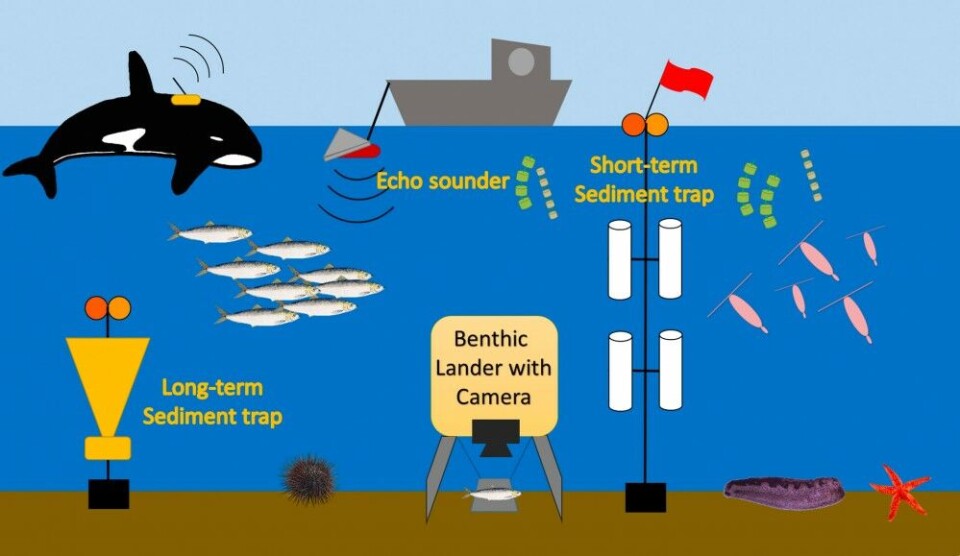

Today’s team was Angelika Renner, Zoe Walker, Ingrid Wiedmann, and Martin Biuw. We were out in Kaldfjord this morning to recover a short-term sediment trap array that consists of a surface buoy, a 130 m long rope and a 20 kg anchor at the bottom. Cylindrical tubes are attached to the rope at different depths; they collect the material that sinks out of the water above over a 24-hour period. But then, while we were hauling in the trap array, the winch broke. Dragging up almost 50 kg of equipment on a thin slippery rope is challenging and quickly turned into a strength training session. Even our boat’s helmsman Martin had to join in, but in the end, the equipment and samples were on deck. Clear conclusion: next time we need a better winch and, just in case, more muscle power onboard!

Why were four scientists out in Kaldfjord, struggling in the winter weather?

It all started in winter 2010/2011 when herring suddenly entered the local ecosystem in Kaldfjord for the first time in years. So much herring, in fact, that their presence affected the entire ecosystem – changing the chemical composition of the water and attracting hundreds of humpback, killer and fin whales, as well as a large fishing fleet. Based on echo-sounder surveys conducted in the Fram Centre project weShare, we estimated the total herring biomass in the winter 2014/2015 to be 1 500 000 tonnes. This means that about 25% of that season’s total Norwegian spring-spawning herring stock was present in Kaldfjord. weShare data also suggest that the 400 humpback whales, the killer whales, and the fin whales visiting the fjord the same winter consumed about 36 000 tonnes of herring, a number very similar to the herring catches by commercial fisheries (about 37 000 tonnes in Kaldfjord/Vengsøyfjord in winter 2014/2015). Combined, whales and fisheries took approximately 5% of the estimated herring biomass in Kaldfjord and Vengsøyfjord.

2.

Prompted by the high number of whales in Kaldfjord, more than 34 whale watching tour operators emerged in the fjords near Tromsø between 2011 and 2016. The increased level of activity by whale watching vessels, numerous fishing vessels and a large number of private boats resulted in various undesirable whale–human interactions such as ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear or cables. The situation in Kaldfjord demonstrated clearly that there is a substantial need to assess local whale behaviour (e.g. diving patterns) and long-term migrations to be able to better handle whale–human interactions. Researchers in weShare contribute to this understanding in collaboration with colleagues from the University of St. Andrews (Scotland).

The movement of three whales in Kaldfjorden between 27 and 29 November 2014, in a relationship with the estimated herring biomass, and shipping and fishing activities during the same days. Whale movement was reconstructed based on GPS instruments that were mounted with suction cups on the whales. The herring biomass is estimated based on echosounder surveys.

In autumn 2016, dedicated hydrographic surveys were conducted in Kaldfjord to supplement the herring surveys, and in 2017, two additional Fram Centre projects joined weShare to form an integrated study of the fjord ecosystem. The project WHALE looks into the physical, chemical and biogeochemical processes in the water column, while the project EFFECTS, together with the project JellyFarm, funded by the Research Council of Norway, studies the effects of herring and aquaculture on the benthic community.

Beyond providing a highly integrated and interdisciplinary collaboration, the projects also stand out for the high numbers of women among the research team, students, and early career researchers involved. Students at all levels of education (Bachelor to PhD) from UiT, the University of Oslo, and even the University Centre of the Westfjords in Iceland contribute to the different projects. Several female postdoctoral researchers took on leading roles. We thank the Fram Centre for providing additional incentive funding to support the training and network building of these young scientists.

Figure: The movement of three whales in Kaldfjorden between 27 and 29 November 2014, in relationship with the estimated herring biomass, and shipping and fishing activities during the same days. Whale movement was reconstructed based on GPS instruments that were mounted with suction cups on the whales. The herring biomass is estimated based on echo sounder surveys.

3.

Fast forward to July 2018. Kathy Dunlop and Paul Renaud are out on the fjord on a beautiful summer day, in stark contrast to the winter sampling. They are there to retrieve the long-term sediment traps that have been at the bottom of Kaldfjord for 10 months. Together with colleagues from Laval University (Canada) and aided by a powerful winch and strong crew, they quickly get their equipment out of the water, back on deck, and to the lab.

By September 2018, a year of monthly surveys, mooring deployments and recoveries, sediment coring, and herring baiting was over: days filled with wind, waves, and waiting for the best weather window. We have undertaken research cruises on small aluminium boats and on some of Norway’s largest research vessels, including the new icebreaker RV Kronprins Haakon. We have investigated the Kaldfjord system from the weather at the top, through the visible and non-visible things in the water column, to the fjord seafloor, its bottom-dwellers and sediments. We spent many hours in the lab analysing our samples, and even more hours in front of a computer to make sense of the numbers. Jofrid Skarðhamar and Qin Zhou (Akvaplan-niva) set up two computer models of the fjord circulation to fill in some of the gaps in our observations. The models provide information on how the currents vary in time and space, and how the water masses circulate in the fjord. Combining model results with the field observations helps us understand the physical processes that affect the transport of plankton and particle flux, and maybe even the presence of herring and whales.

What we find is a surprisingly dynamic environment in this relatively small fjord.

Seasonality is a major driver of the physical and biological processes in the fjord, but already from this short study, we can see large interannual variability. Master’s student Zoe Walker showed how changes in weather patterns such as winter droughts or strong unseasonal wind events have an immediate effect on the hydrography, affecting fluxes from the surface waters to the benthos. Organic particles sinking from the fjord surface provide a food supply to the fjord seafloor ecosystem and understanding the dynamics of this flux is a key goal of both short- and long-term sediment trap deployments.

The traps have allowed us to resolve a clear annual seasonal pattern in carbon flux, which will prove valuable in understanding the functioning of sub-Arctic fjord ecosystems.

Postgraduate students Anouk Klootwijk and Hege Vågen from the University of Oslo studied seafloor communities, which rely on the particle food supply from the water column, and their functioning in Kaldfjord. They chose to study benthic foraminifera, which has been described as a lens into the present and past environments because foraminifera is so abundant, widespread and sensitive to environmental changes.

Great value

Kaldfjord has great value for the inhabitants of Tromsø and the coastal community thanks to its proximity and the recreational opportunities it offers, but also for aquaculture, fishing and industrial activities. Many people are very interested in our research, curious to see how our work will contribute to solutions for more sustainable use of the fjord. Analyses of our field and model data are yielding results, and the next year will be spent confirming these results, and publishing and communicating them to both the scientific and the local communities.

Now that the herring, the whales, the fishing fleet, and the whale watching operators have moved on, other fjords are experiencing a situation similar to that seen in Kaldfjord a few years ago. Our integrated ecosystem study in Kaldfjord can provide valuable information for impact assessments and management in these areas. We hope it will also contribute to sustainable use of northern fjords, allowing fish, whales, and humans to live here together.

This story is orginally published by the Fram Forum