Sami children in new education rooms

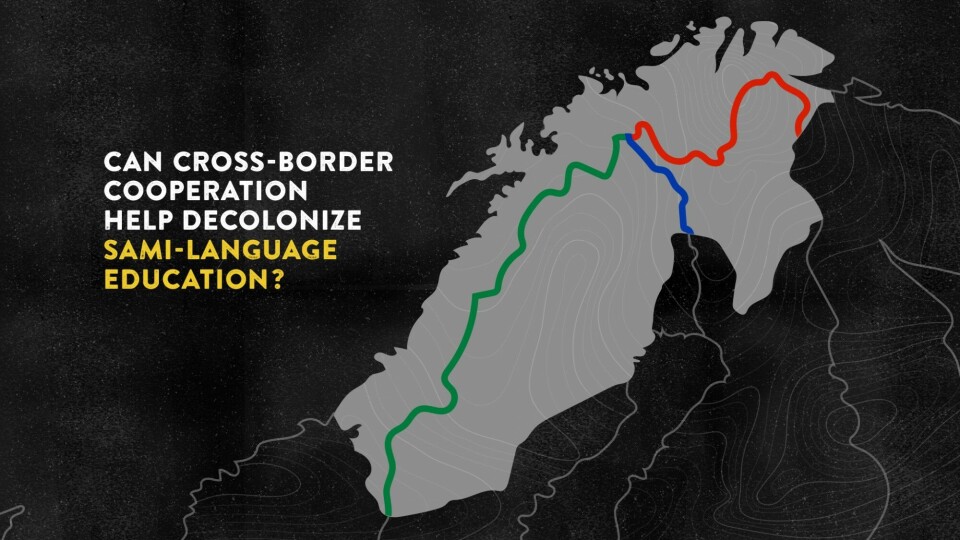

KIRUNA, Sweden - An ambitious project to transform early childhood education for Sami children in Norway, Finland and Sweden, is getting underway, with authorities in Norway currently selecting the first nine preschools to pilot the project.

By Eilís Quinn, Eye on the Arctic

The five-year project, called SaMOS — Sami manat odda searvelanjain (“Sami children in new education rooms”), was started in 2017 to improve and provide culturally relevant education for Sami children.

Since then, representatives from the Sami parliaments in the three countries have been working together to completely change the way early childhood education is delivered both in terms of content and ways of teaching.

“The main goal of this project is to go back to the beginning and define: What is the Sami way of education?,” says Ol-Johan Sikku, project leader at the Sami Parliament in Norway. “Because no one has answered that yet, that’s what we’re working to define. Because once it is, and we know how Sami children are best taught, it will reinforce everything from culture and traditional knowledge to language.

“And that’s so important because now, no matter what country we’re in, our children are educated in a dominant culture that’s not our own.