Pollutants in ocean’s giants

Blue whales and fin whales are the largest creatures on our planet. Human activities have posed challenges to their survival for more than a century. Industrial hunting severely reduced their numbers. Now they are threatened by a host of man-made alterations in their habitat – including pollutants.

By: Heli Routti, Katharina Luhmann, Kit M Kovacs and Christian Lydersen // Norwegian Polar Institute. Mikael Harju // NILU – Norwegian Institute for Air Research. Anders Goksøyr // University of Bergen

During the industrial whaling period in the 20th century, over a million blue whales and fin whales were removed from the world’s oceans. Populations are recovering, but these giants are still classified as Endangered and Vulnerable, respectively, on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Current threats include entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes, underwater noise, climate-change-induced alterations of ecosystems, and pollution. Little is known about pollutant exposure of these animals, but they are likely exposed to a wide variety of chemicals during their cycles of movement across ocean basins.

In addition, the whales’ long life-span and their potentially limited ability to transform pollutants into a form that can be excreted from the body may exacerbate the problem.

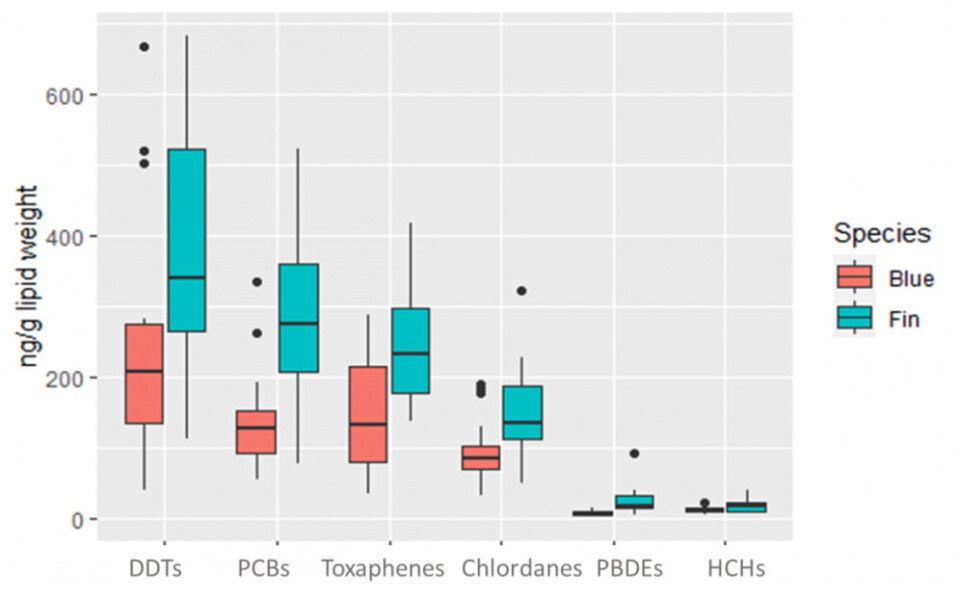

Our research project, funded by the Fram Centre’s Hazardous Substances Flagship has provided a lot of new knowledge regarding pollutants in blue whales and fin whales that reside around Svalbard during summer. We have detected a wide range of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the 30 whale blubber biopsies that we collected between 2014 and 2018. POPs are man-made chemicals that have been used extensively in the past for agricultural and industrial applications. Many of them have been banned for decades, but due to their persistence they are still present in the environment and in living organisms.

We find that POP levels are two to three times higher in fin whales than in blue whales. This difference is likely related to their respective diets. Blue whales feed almost exclusively on krill, whereas fin whales also eat large zooplankton and small fish. Pollutant levels in males are twice as high as in females, because females transfer some of the pollutant loads to their calves via milk during the lactation period.

Pollutant levels in blue whales and fin whales from Svalbard waters were much lower than those documented in conspecifics sampled closer to areas with dense human populations.

We have also analysed plastic additives in blubber samples from blue and fin whales. Phthalates are widely used to impart flexibility to plastics. Although the use of some phthalates has been restricted in Europe, their global production is still millions of tonnes yearly. We detected phthalates in whale blubber samples at concentrations similar to those of well-known legacy POPs such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and the pesticide DDT. Like PCBs and DDT, phthalates are transported to the Arctic via air currents. Once deposited from the air into seawater they are taken up by plankton and are subsequently consumed by whales and other animals through their diet. Ingestion of plastic litter is also a potential source for phthalate exposure in blue whales and fin whales.

Studying potential health effects of pollutants in large whales is very challenging. However, a small biopsy can be used to get insights on the effects of pollutants at molecular and cellular levels. We have used advanced DNA technology to establish assays that allow us to study effects of emerging and legacy pollutants at a molecular level. Our assays help us understand whether pollutants can perturb the function of specific proteins in whale cell nuclei that play a central role in metabolism and are normally activated by natural hormones and lipids.

We observed that POPs found in whale blubber, in particular DDT, impaired the function of these important metabolic proteins. The perturbations were detected at concentrations mimicking those found in killer whales from Arctic waters. Similarly, we found that phthalates may potentially disturb protein function in whales. Thankfully, these effects are exerted at pollutant levels considerably higher than those we found in blue whales and fin whales from Svalbard waters.

Further reading:

- Tartu S, Fisk A T, Götsch A, Kovacs KM, Lydersen C, Routti H (2020)First assessment of pollutant exposure in two balaenopterid whale populations sampled in the Svalbard Archipelago, Norway. Science of The Total Environment 718: 137327

- Lühmann K, Lille-Langøy R, Øygarden L, Kovacs KM, Lydersen C, Goksøyr A, Routti H (2020)Environmental pollutants modulate transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors of whales in vitro. Environmental Science & Technology 54: 5629−5639,(requires subscription)

- Routti H, Harju M, Lühmann K, Aars J, Ask A, Goksøyr A, Kovacs KM, Lydersen C (2021) Concentrations and endocrine disruptive potential of phthalates in marine mammals from the Norwegian Arctic. Environment International, Forthcoming

This story was originally published by the Fram Forum