Can we convince tourists to go hiking without leaving any traces?

A growing number of people are visiting Norway’s protected areas. This poses new challenges for national park management. Excrement and rubbish left behind by thousands of tourists degrades Lofotodden National Park’s idyllic nature. What can be done about this problem?

By: Anne Olga Syverhuset, Sigrid Engen and Rose Keller // Norwegian Institute for Nature Research – NINA

“When nature calls” Norwegians are used to being able to go behind a rock to relieve themselves without causing a nuisance to other people. This is not necessarily the case anymore. If you go behind a rock these days you may discover that a lot of people have been there before you,” says Sigrid Engen, a scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA).

Together with her colleague, Rose Keller, she is studying the impacts of a high numbers of visitors to protected areas and how refuse and excrement affect the visitor experience. They are also asking how we can reduce the negative impacts of tourism.

There has been a steep increase in the number of tourists visiting Norwegian national parks in the last decade. While tourism can help boost the income of local businesses, it can also displace local people from popular recreation sites. Trampling effects (leading to muddy and slippery trails), rubbish, and congestion could spoil people’s perceptions of the environment as pristine and cause locals to go elsewhere for their outdoor activities.

Mapping and monitoring human waste

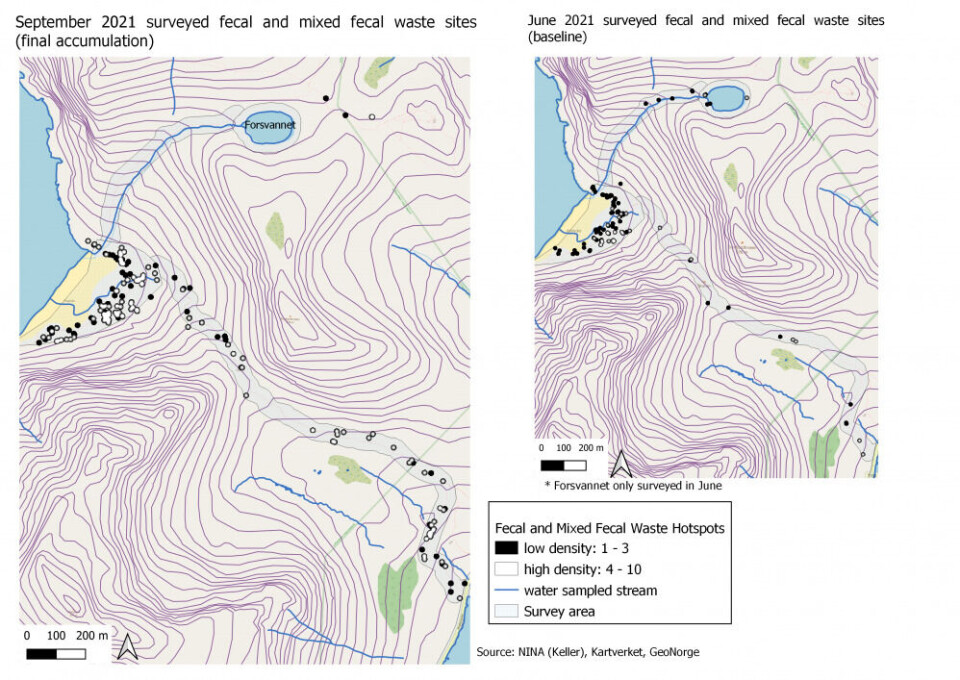

This summer, as part of a pilot project entitled Traceless Tourism, Engen, Keller and their students Hennie Lindøe and Eirik Sønstevold tested a mapping method to record the location and density of human faeces and other types of human waste such as toilet paper and wet wipes. The pilot project began after the manager of the Lofotodden National Park, Ole-Jakob Kvalshaug, contacted NINA with a request to investigate what they could do to solve the human waste problem.

Method development and testing took place along the path to and in the area around the popular beach in Kvalvika, which is part of Lofotodden National Park. Another beach with fewer visitors, Vinjestranda in Vågan municipality, was also included in the work.

“It takes an hour and a half to walk to Kvalvika and a lot of people camp here. Challenges with the accumulation of human waste arise when a lot of people camp in a relatively small and inaccessible area,” says Engen, who remembers the beach as being an idyllic, quiet, and lesser-known place when she was a child.

Since Kvalvika is located within the boundaries of a national park, strict restrictions limit development of infrastructure such as toilets, according to Engen. This means that anyone who leaves the beaten track or ventures in behind a big boulder near the beach might be in for an unpleasant surprise.

And that is exactly what the research team did during the summer of 2021. They visited places where people might go “when nature calls” and documented what they found behind rocks and bushes in an area extending 30 metres away from the trail on both sides. Each discovery was catalogued and recorded using an app that allowed data to be imported into a geographic information systems (GIS) program. A tampon here. Toilet paper there. Dog poo bags, wet wipes, and the remains of campfires.

Based on their investigations, they have produced a map showing the locations of most of the human waste left behind.

Hotspots near drinking water

Their survey revealed unpleasant “hotspots” where rather large quantities of excrement were found. Most of these hotspots were located near the camping sites along the beach.

“Some particularly worrisome ‘hotspots’ were located right next to streams where we observed people filling their water bottles,” says Keller.

The researchers took water samples in August 2021 and found relatively high levels of E. coli bacteria in two of three of the streams they sampled, including one where they saw tourists collecting drinking water. More research is needed to determine whether the source of the E. coli is predominantly human.

Available facilities not used

Human waste hotspots close to sources of drinking water show how important it is to take tourists’ toilet needs seriously. However, protected area regulations are strict. The regulations for Lofotodden National Park stipulate: “The area is protected from encroachments of any kind, including the construction of permanent or temporary buildings, facilities, and installations….” So you can’t simply put up a toilet.

And even when there are toilets, such as at the car park at the start of the path leading to Kvalvika, not everyone uses the facilities that are available. We know this because the researchers found a lot of excrement 0.75 to 1 kilometre from the trailhead.

“This could mean that the toilets should not be in the car park, but instead somewhere along the first kilometre of the trail,” Keller points out.

In other words, identifying the specific nature of the problem of human waste is important for finding the best solutions.

Can we achieve Traceless Tourism?

At present little or no information is provided for tourists entering Lofotodden National Park when it comes to dealing with human waste.

“The new Visitor Centre in Reine, which opened in June 2021, could potentially provide guidelines on what tourists should do with their waste at Lofotodden and in Lofoten in general, but neither the educational exhibits nor the staff currently try to influence the visitors’ behaviour,” says Keller.

Keller has experienced the same problems in Denali National Park in Alaska, where waste generated by tourists has been a challenge for many years. She explains that it is important to identify the attitudes that prompt this kind of behaviour in order to ensure that visitors “get the message”. So you need to know more about who is visiting the area and tailor your message accordingly.

“In Denali, the park managers thought that people would not change their behaviour, since the problem was not solved by putting up signs and installing rubbish bins. After we examined what kind of people visited the park, what attitudes they had, and what prevented them from changing their behaviour, we found that we could change these attitudes by addressing them directly. And we discovered that the rubbish bins had been installed in the wrong places,” says Keller.

When they applied this knowledge, they managed to get visitors to change their behaviour.

Keller emphasises how important it is to have a clear idea about what kind of behaviour you want to encourage if you want people to change their ways.

Should tourists be encouraged to bring their own waste bags and deposit their waste in the nearest rubbish bin? Or is it enough to provide clearer guidelines on where they should (and should not) relieve themselves?

Should we establish better infrastructure with more toilets? If so, who should be responsible for the cost of maintenance and cleaning? And how can we get the tourists to use them?

Human waste is not the only problem

A high number of visitors also creates other new challenges. How do you get visitors to stay on the trail? How does seeing and hearing other people impact the wilderness experience? How can we prevent people from building dozens of rock cairns?

Justice issues related to access to the public right of access are also a concern for Engen.

“A high number of visitors leads to a greater need for regulating access to popular areas. Examples include restrictions and fees on parking, bans on camping, and admission fees,” says Engen.

We saw examples of bans on tenting in Lofoten this summer when local politicians felt obliged to introduce such restrictions in some places.

“We risk having to limit the public right of access, which in turn may negatively impact people who seek simple low-cost outdoor activities, while benefitting visitors who want a higher degree of comfort and facilitation – people who can afford to pay for hotel accommodation or a camping site when the options for tenting and parking are limited,” says Engen.

Keller and Engen conclude that all the findings from this summer’s pilot project highlight the need for more knowledge about the visitors, where they find information about how to behave when hiking in Norway, the timing and content of messages provided to visitors, and about possible solutions in the form of new infrastructure or using pack-out waste bags.