Sámi representatives in COP26 raise concerns over 'green colonialism'

When world leaders, climate activists and decision makers gathered in Glasgow for the 26th UN Climate Change Conference, many people raised their voice for the lack of indigenous representation. While the changing travel restrictions, Covid-19 situation and increasingly expensive travel and accommodation has prevented many people from attending, the Sámi community has been involved closely in this year’s conference. Ranging from politicians to activists and even religious leaders, the Sámi representatives have worked to bring up issues of green colonialism and the already showing effects of climate change.

As previously reported, the effects of climate change can already be seen in the north and in the circumpolar areas - many indigenous people in the global south and the circumpolar areas live in territories where even minor changes to the climate can have drastic impacts on traditional livelihoods and culture. First hand accounts of people affected by these changes are crucial in order to understand the larger impacts already happening. In addition, the importance of indigenous knowledge on helping climate change mitigation cannot be ignored.

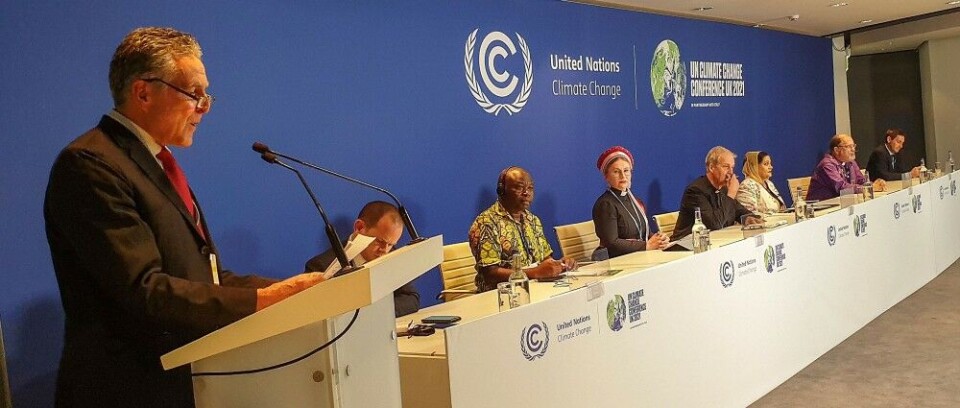

This year’s UN’s Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26, has connected various Sámi representatives, activists and politicians with world leaders and like minded individuals. Reverend Mari Valjakka, a Sámi pastor at Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was at the spot to represent not only the Skolt Sámi community, but also the World Council of Churches and its Indigenous Peoples Network.

During her time at COP26, Valjakka has brought up the issue of green colonialism - the practise of exploiting indigenous lands on the excuse of renewable energy. This can happen in the form of proposed wind farms in the fells of Sámi area, which reduce the living space of reindeer and consequently has direct effects to the right of the Sámi to practise their traditional livelihoods. Mines are also a cause for concern, since growing demand for batteries for electric cars require minerals which have still been untapped in the Sámi areas. Valjakka explains that green colonialism is almost a by-product of trying to achieve renewable energy solutions such as wind farms. ‘It has been a centre of discussion, do indigenous people carry the burden when renewable energies are developed - whether it is wind farms in Sámi homeland or hydroelectricity in the Amazons,’ she says. Many indigenous communities see this ‘new form of colonialism’ as essentially harmful to traditional lifestyles, especially due to the already decreased living spaces. Indigenous people around the globe must fight the effects of climate change, while fighting for their living space.

Valjakka has been sending a message of indigenous people’s struggles with climate change to and with the world’s religious leaders. “After all, the problems are similar no matter if it is indigenous peoples in the Pacific areas, in the Amazons, in Asia or in the Arctic, the effects can be seen all around the world but often our voices are not heard,” Valjakka explains. Additionally, Valjakka would like to draw attention to the people who are not represented at COP26 this year; “Other indigenous people and marginalised groups are not heavily represented … and we should also think about the chairs that are empty. Indigenous peoples, marginalised groups, poor people and everyone who has not been able to attend for one reason or another,” she says.

While Valjakka is pleased that there is solidarity shown between indigenous people in the world, she also hopes for more from the world leaders; ‘I see that indigenous people strongly support each other and know the realities of our lives,’ Valjakka says. She goes on to explain that she wishes that indigenous people are not invited just ‘for show’ but that in the future indigenous people would really be consulted on issues that directly affect them. ‘We really need to be included and gathered at the tables where decisions are made,” she says.

“In my opinion, there is no climate justice if there is no justice for indigenous people,” Valjakka concludes.

Bringing Sámi viewpoint to this year’s discussion is also Pirita Näkkäläjärvi, a Sámi politician and has a long career in international business. For this year’s climate conference, she led a panel discussion as a part of Goethe Institute’s Right to Be Cold project. The project’s panel discussion centred around issues concerning indigenous people and climate change, as well as the previously mentioned green colonialism. The panel discussion consisted of representatives from the Sámi area, Nunavut, Yakutia and other Arctic regions, linking together indigenous peoples, climate change and energy transition.

Having had a long career in international business, Näkkäläjärvi underlines the importance of the responsibility of businesses in the fight against climate change. In the panel discussion, Näkkäläjärvi brought up her on reflections on the conflict between working between different sectors; “I have worked with industrial companies and energy corporations as a management consultant, while working towards strengthening indigenous rights as a member of the Sámi Parliament,” Näkkäläjärvi says. She talks openly about the feelings that are brought up when working in fields that are often in conflict with each other and can have vastly different values and targets. “Sámi have already given a lot of land to for example hydro power and logging. Besides, there are several municipalities in Finland that welcome wind power with open arms,” Näkkäläjärvi continues.

“These things are not always black and white - not wanting wind power in the Sámi homelands does not mean that we are against renewable energy,” Näkkäläjärvi says. “But we are able to work in a way that respects indigenous rights and allows traditional livelihoods to thrive, and it is most likely possible,” she continues.

Näkkäläjärvi states that during her 15-year long career, the interests of environmentalists and large corporations are more aligned than ever. “We are trying to build momentum and sense of urgency,” she says. The hope is to get the message through to bigger states and corporations who truly have power in climate action. “The general message is that people have truly realised that something has to be done to keep the 1.5 degrees alive,” Näkkäläjärvi explains the feelings at COP26 and mentions the overarching goal of the summit to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius. “Evidently a lot of companies that have a crucial role in the change have stepped up and are truly trying to make a difference,” she continues. Näkkäläjärvi is optimistic about this development, but does hope that this enthusiasm does not die down and have little results in the end.

While it is positive that climate action has piqued the interest of big agents, there are still doubts on whether or not listening to indigenous concerns is merely performative. Mari Valjakka explains that “We have gotten our voices heard somewhat … I would wish for more real action in addition to the beautiful speeches.”

Näkkäläjärvi echoes these thoughts; “There has been a little bit of hopelessness,” she says. “I tried to bring up what I could, but I also have a feeling of what can a small person representing a small group of people actually do. We did what we could, whether or not we are actually listened to - I have conflicting feelings about that,” she concludes.

Indigenous communities face various challenges due to climate change, no matter where they live, the sensitive climate is not quick to adapt to changes. Indigenous communities around the globe are concerned over green colonialism and fear that their shared living spaces are overshadowed by wind farms, hydroelectric plants or mines. This year’s climate change conference saw more corporate leaders than any other year - the hope is that these leaders have been in the right places and listening to the indigenous concerns.