"It demonstrates the potential enormity of the problems society may face over the coming centuries" UiT scientists on the new data from the Barents Sea.

New Barents Sea study points to how global sea level will continue to rise.

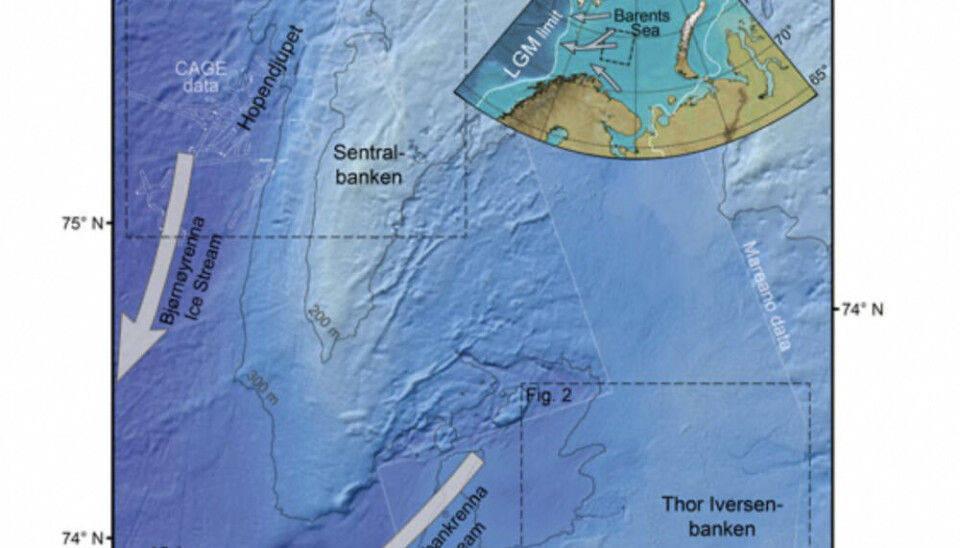

A recently published study from geologists at UiT The Arctic University of Norway has provided new insight into what was happening beneath the Barents Sea ice sheet around 15,000 years ago. The data gathered will help to better understand the processes occurring under present-day climate change.

What was discovered?

According to a global consensus of scientists it is virtually certain that global sea level will continue to rise over the 21st century. For the 900 million people (1 in 10 globally) living in coastal zones around the world now, including in coastal mega-cities, this danger is particularly acute.

“Unravelling the glacial changes that occurred in the marine setting of the Barents Sea during the warming at the end of the last ice age is important as it gives us a unique long-term perspective into how ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica today could respond in the future.” UiT researcher Dr Henry Patton says to The Barents Observer.

For the first time, this research which has been conducted over the last 5 years, has put some numbers on how fast this former ice sheet in the Barents Sea retreated.

“Like the present-day ice sheets, this Barents Sea ice sheet was immense, reaching up to 3 km thick in places, but we are starting to think that the whole system collapsed very quickly, raising global sea level by many metres in just a few centuries,” says Patton.

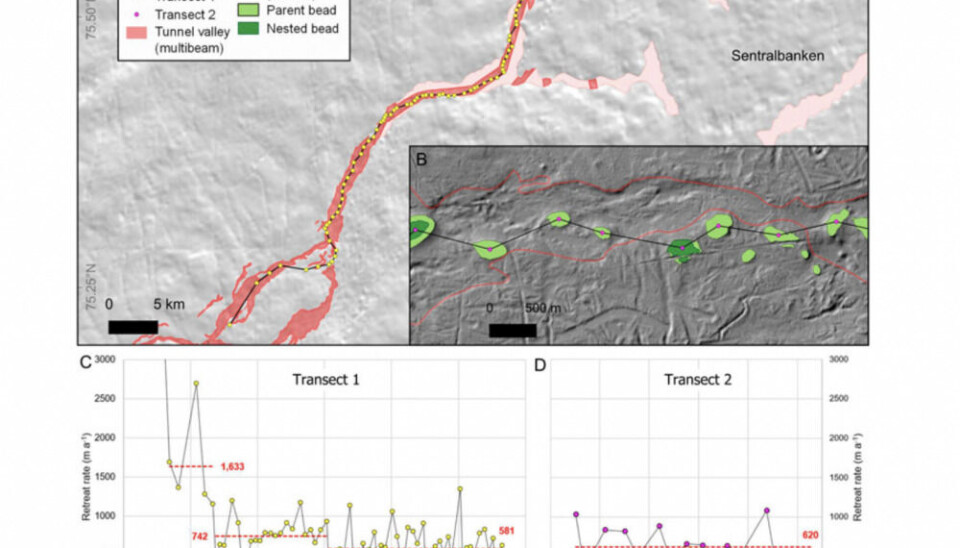

Newly discovered seafloor deposits have provided new information on how fast this vast ice sheet was shrinking through the central Barents Sea 15,000 years ago. The data the team found shows the ice sheet was retreating between 580 and 1600 m per year on average, for at least 91 years. At this pace, most of the ice sheet is likely to have disappeared from across the entire Barents Sea within 1000 years, raising global sea level by around 6 m in the process.

This geological data shows that the continuous, fast retreat of ice sheets over many decades, and possibly centuries, is not unprecedented under a rapidly changing climate. Chronological data constraining this ice-sheet collapse has previously been a long-standing knowledge gap.

“If our numbers are correct this collapse event would have contributed to an extraordinarily fast pace of sea level rise, - Dr Patton says - and it demonstrates the potential enormity of the problems society may face over the coming centuries if the current ice sheets continue to destabilise”.

Yet, he added, pinning down these future quantities of melt over the coming decades and centuries is not straightforward as the feedbacks that operate between the oceans, climate and ice are highly nonlinear.

How was it done?

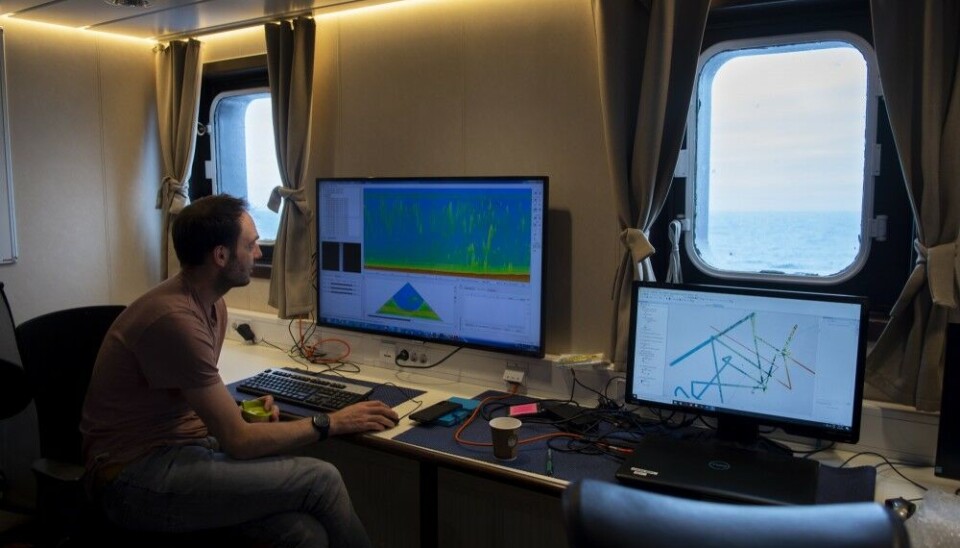

To uncover information about the glacial past published in this study, the UiT team has been surveying and mapping the Barents Sea area from research vessels since 2020. Sometimes scientists would stay on the research ship for up to three weeks. The team in their research also incorporated open data collected by the Norwegian Hydrographic Service through the MAREANO programme.

By piecing together these high-resolution snapshots surveyed from the Barents Sea floor - like in a jigsaw puzzle - a clearer picture of the glacial history of this region can emerge. The mapping included in this UiT study comes from a very remote region in the central Barents Sea, near the Norwegian - Russian border. Scientists believe this region hosted some of the last remnants of the last ice sheet before it finally melted away.

- Here you can use a map demonstrating an interactive reconstruction of the Eurasian ice sheet during the last ice age

Such observational data are vital for guiding numerical simulations that try to reconstruct the behaviour of the old ice sheets. Lead researcher of the study, Dr Calvin Shackleton from the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, points out that satellite data, which has been used to monitor the present-day ice sheets over the last 40 years, are unable to observe the processes happening underneath the ice sheet. This makes the geological data left behind by these older ice sheets like in the Barents Sea such a valuable archive to investigate.

“The detection of traces of water at the interface between the ice sheet and seafloor is of importance as the water acts as a lubrication, allowing the ice above to flow faster and thus more quickly transfer its mass to the more climate-sensitive regions at lower elevations.”

Why is this important?

Continued sea level rise is one of the most concerning processes occurring around the planet now. There have been multiple statements at the highest political levels about an existential threat not only for big cities from London to Shanghai, but also for many small island nations.

Earlier this year the UN Secretary-General António Guterres pointed out in a statement: “For the hundreds of millions of people living in small island developing States and other low-lying coastal areas around the world, sea-level rise is a torrent of trouble….The impact of rising seas is already creating new sources of instability and conflict” he said.

According to Dr Patton, quantifying this sea level rise and being able to adapt to its impacts are key aspects driving the need to better understand the science behind present-day climate change. Specifically, as he says, it’s now visible from how water carved the seafloor and deposited sediments that meltwater was abundant beneath the Barents Sea ice sheet, and thus able to regulate how the ice above flowed as it collapsed. Some of this water, researchers think, was fed from the ice-sheet surface, showing that this Arctic ice sheet was increasingly susceptible to melting as temperatures in the atmosphere rose.

Another recent study has similarly mapped glacial landforms in the Norwegian Sea, showing how fast the last ice sheet over Scandinavia retreated back into Norway at around the same time the Barents Sea ice sheet was also collapsing. The rates they found are exceptionally higher, at 55 to 610 m per day (in comparison to the 580 to 1600 m per year from UiT), and faster than anything ever observed today or in the last ice age. These very fast rates, however, were likely only ever sustained over a period of days to months.

Nevertheless, both studies highlight the profound speed by which ice sheets can quickly destabilise and lose mass, and provide a strong warning on the importance of better understanding the nature of contemporary climate change and its impact on society. People need to know what dangers to face in the future. But, as scientists say, the research is still ongoing: