“Skottelus” – the smaller relative of the salmon sea louse

In Norway, salmon farming is considered to threaten wild salmonids mainly in two ways. First, fish that escape from captivity might crossbreed with wild salmon. Second, farmed fish often carry a parasite – the salmon sea louse. But salmon farms are also plagued by another sea louse…

By: Kjetil Sagerup, Mette Remen, Karin Block-Hansen and Albert D Imsland // Akvaplan-niva. Willy Hemmingsen // UiT The Arctic University of Norway. Ken MacKenzie // University of Aberdeen.

A few years ago, Norway introduced a “traffic light system” (Trafikklyssystemet) to regulate expansion of salmon aquaculture. In regions given a green light, salmon production may increase by 6%. Regions with a red light must reduce production by 6%. A yellow light signals no change. The salmon sea louse (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) is presently the most important environmental indicator this system.

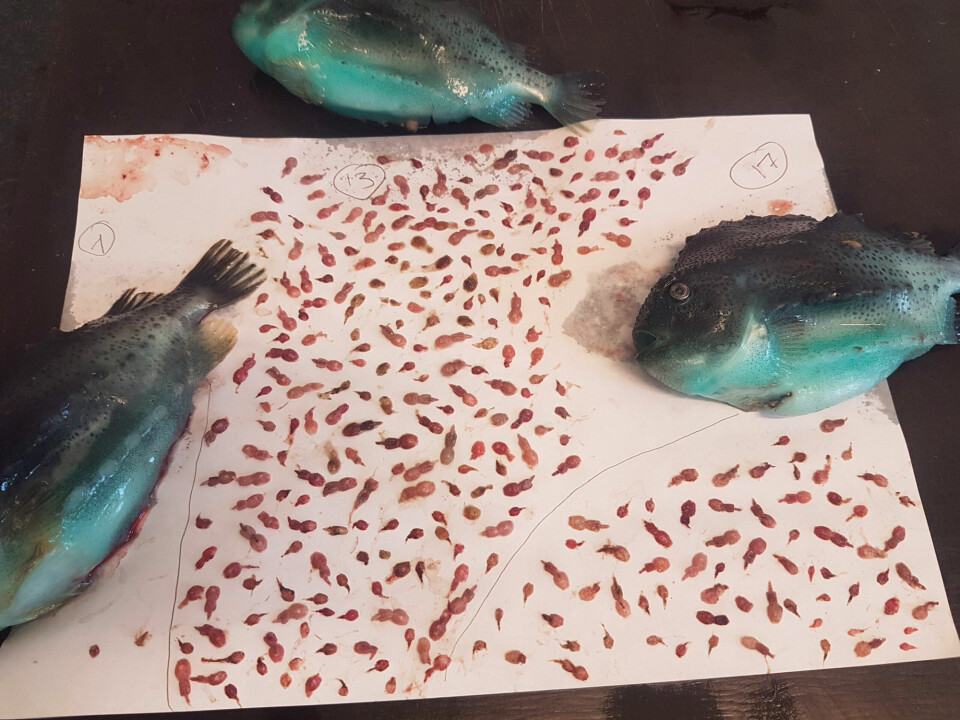

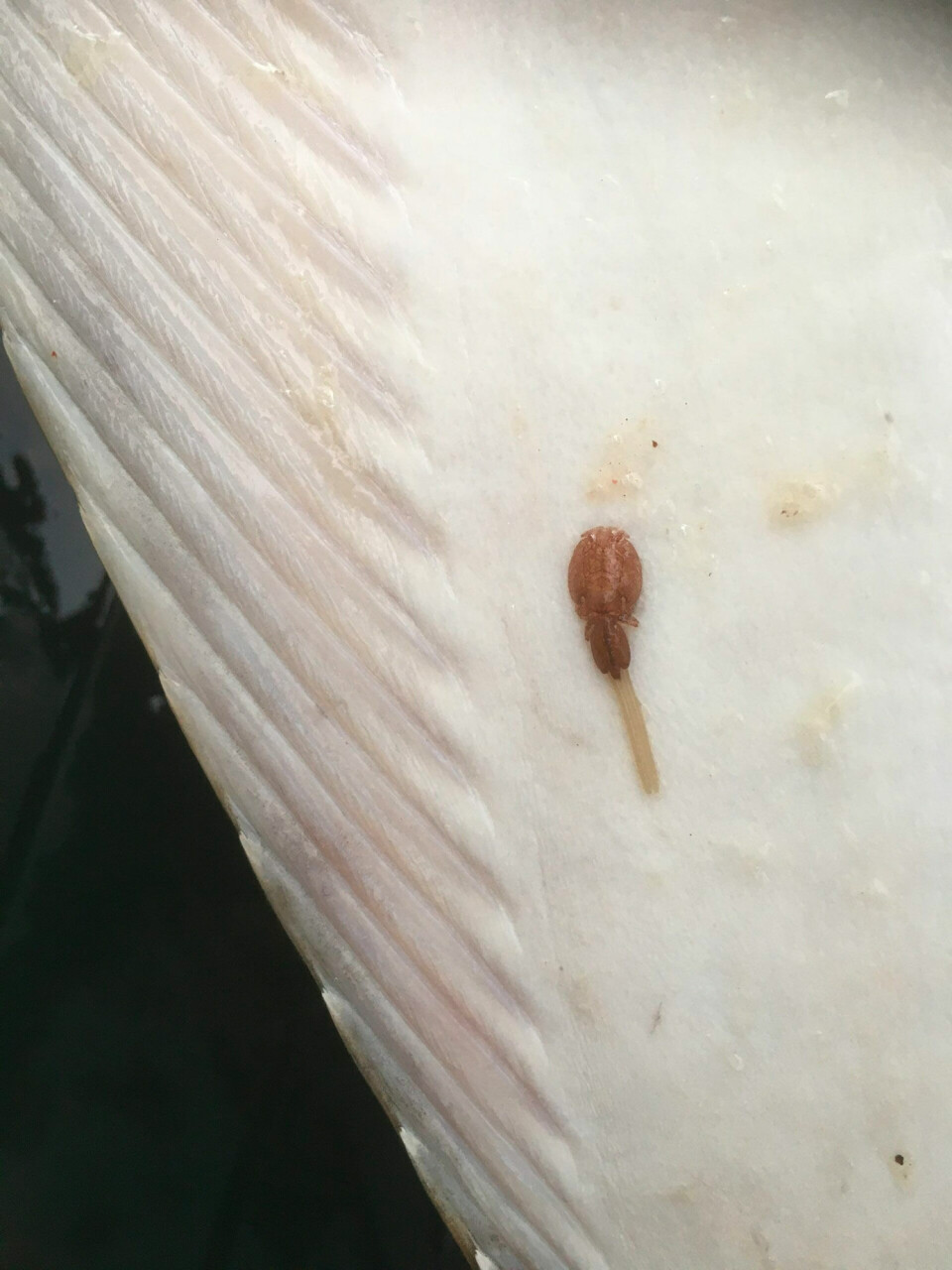

The salmon sea louse has smaller relative, Caligus elongatus, which also infects salmon. In Norwegian, C. elongatus is called Skottelus, which means “Scotland sea louse”, but this is not an accepted common name in English, so in this article we will refer to it by its Latin name. Caligus elongatus is a parasitic copepod of the family Caligidae. Females of C. elongatus are much smaller than female salmon sea lice, while the two males are of similar sizes.

One major difference between the salmon sea louse and C. elongatus is their host preferences. The salmon sea louse is essentially a parasite on salmonid fish. Reports of non-salmonid hosts are rare. A non-salmonid host would probably not support maturation of salmon sea lice to adults that can reproduce and ensure survival of the species. C. elongatus on the other hand has a very low host specificity and infestation with these parasites has been reported on more than 80 different fish species. In Norwegian waters C. elongatus infestations are common on schooling fish such as saithe and herring. Infections of farmed salmon by C. elongatus have been assumed to be connected to passing schools of fish.

In northern parts of Norway, a high abundance of C. elongatus on farmed fish is frequent in autumn and winter. According to fish health personnel in northern Norway, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, C. elongatus represents a threat to the welfare of farmed salmon even at light infestation levels – at least when the salmon are small. Infestations are typically manifested by increased jumping activity among the fish, with subsequent bruises and abrasions, loss of appetite, skin irritation, and secondary infections due to the lice feeding on the mucus covering the skin.

Both salmon sea lice and C. elongatus have short growth cycles and thus a huge potential to spread infections. The complete generation time of C. elongatus is approximately five weeks at 10°C, and slightly longer for the salmon sea louse. Another difference between the species is that C. elongatus is a much better swimmer than the salmon sea louse. This, along with the fact that mature C. elongatus infect species like saithe and herring, should help explain the rapid increase of C. elongatus in sea pens during certain periods of the year in northern Norway. In addition, reports of large numbers of larval stages on farmed salmon – without any corresponding increase in adults – suggests either that the C. elongatus failed to develop to maturity or that they had left the salmon after maturing, possibly moving to wild fish hosts.

Controlling salmon sea lice is one of the biggest challenges in Norwegian salmon farming. In 2014 sea louse costs for the aquaculture industry exceeded NOK 5 billion. This is about 9% of the total income of the Norwegian salmon farming industry. The efficacy of medicinal treatments administered either by bathing or orally, may be negatively affected by the lice developing reduced sensitivity to the treatments, leading to reduced treatment efficacy. In addition, fighting two parasite species with different annual infestation times puts pressure on available tools as there is a limit to how often medical treatment can be used during a production cycle. Therefore, more emphasis has been placed on alternative treatment strategies such as thermolicing, high pressure washing, laser-assisted louse removal, and biological removal using “cleaner fish” that graze on the lice infesting the salmon.

Biological control using cleaner fish is effective in reducing louse density and is widely adopted by the salmon farming industry. The common lumpfish is extensively used to control sea louse infestations in northern Norway, Ireland, Scotland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands. However, there had been little systematic knowledge and guidance regarding the effect of lumpfish on infestations of C. elongatus specifically. Akvaplan-niva has been studying lumpfish grazing of salmon sea lice for almost two decades and can now finally confirm that lumpfish also efficiently graze on C. elongatus.

Our study included an interview survey of fish health personnel working in the salmon farming industry in Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland. Nearly 100% answered our question “Do lumpfish graze on C. elongatus?” in the affirmative. Further, 75% of the respondents from Iceland and the Faroe Islands and 40% of Norwegian respondents answered “yes” to the question “Does lumpfish grazing lead to reduction of C. elongatus on the Atlantic salmon?”

The experimental data in our study show that lumpfish graze on C. elongatus. We find that their grazing activity can be improved by live-feed conditioning the lumpfish before they are transferred to the salmon sea-pens, and through selective breeding. Our next challenge is therefore to selectively breed the lumpfish with the highest propensity to graze on both the small C. elongatus and its larger cousin the salmon sea louse.

The research presented in this article was financed by the Norwegian Seafood Research Fund (FHF-901539), project coordinator Albert KD Imsland, Akvaplan-niva.

This story is originally published bythe Fram Centre