The red king crab: a blacklisted but valuable fisheries resource

With climate change come changes in species distribution. Here in the High North, we expect to see many marine species move northwards. In addition, humans sometimes move species for commercial purposes with varying outcomes. One such species in the red king crab.

By: Jenny Jensen, Magnus Aune, Paul Renaud, Benjamin Merkel and Guttorm Christensen // Akvaplan-niva

Starting in the 1960s, Russian scientists introduced a Pacific marine species, the red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus), to the eastern Barents Sea to establish a new commercial fishery. Following this introduction, we have seen two parallel developments. First, in recent decades, dense aggregations of the species gradually moved into Norwegian waters and south-westwards along the Norwegian coast. Second, as intended by its introduction into the Barents Sea, the crab has indeed become a major harvestable stock, with commercial catches in Norwegian waters worth 30 000 000 Euros in 2019.

However, the red king crab has a destructive impact on the benthic fauna: it has therefore been blacklisted in Norway and the fisheries authorities do not want the species to move further west along the coast. Accordingly, current Norwegian policy is quota regulations east of Nordkapp and free (eradication) fishing in areas farther west.

As red king crabs can be numerous in an area one day and almost completely absent the next, it is tricky to locate them for harvesting. Fishers therefore spend considerable time and burn much fuel searching for crabs. This also causes pollution and climate gas emissions that could be avoided with better information. This is why a group of fishermen from Hammerfest eagerly contacted Akvaplan-niva and asked: “What do the crabs do? And where ARE they?” With funding from the Regional Research Fund North and fishery companies, we started to find answers to their questions.

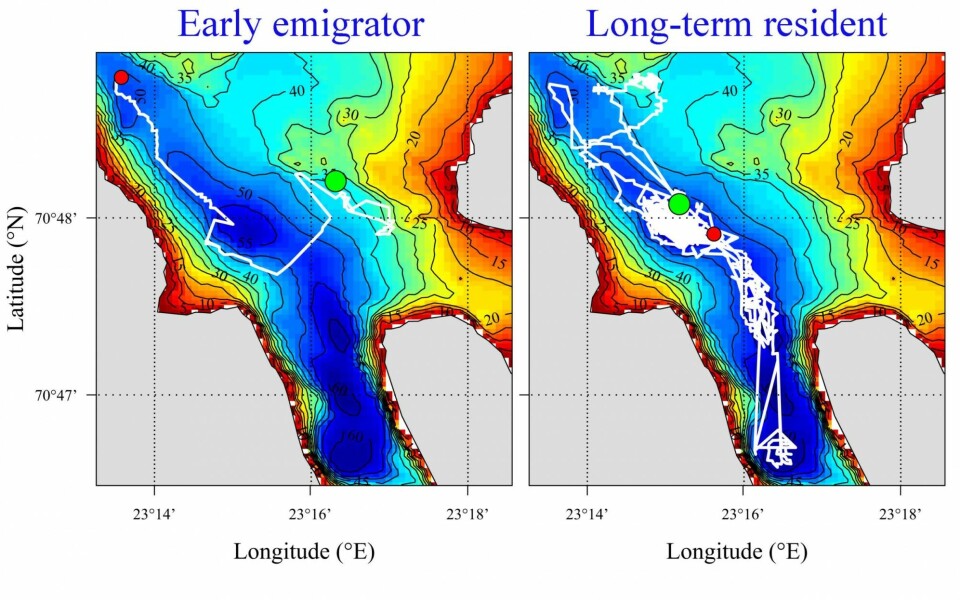

In the study, we equipped 39 crabs with acoustic tags that transmitted a signal telling us the identification code of each individual. These signals were then picked up and stored in receivers that we moored in a grid system in Gamvikfjorden northwest of Hammerfest. By triangulation (using the difference in how long it took for signals to reach different receivers), we could calculate the position of the crabs to within about three metres.

We experienced some challenges with receivers being lost, as the next stop northwards of the study location is the North Pole and the weather can be harsh. In spite of this, we managed to record high-quality data from March to October. The data revealed many interesting aspects of the crab’s habitat use and we found that about half of the tagged crabs left Gamvikfjorden within two weeks after tagging. Three individuals were recaptured in fishing gear as far as 147 km from the tagging location, having moved with average speeds of 200-500 metres per day.

The crabs that remained in the fjord over the summer showed many interesting behavioural patterns. For instance, in late spring when the water masses were cold throughout, the crabs were found both in shallow and deeper waters, likely eating different food types. However, as summer progressed and temperatures rose above ~6°C, the crabs quickly moved into deeper and colder waters. Also, many crabs appeared to be social, walking together almost all the time. These findings confirm that the red king crab can move fast, but also that it has clear temperature preferences. From this, one can make predictions as to where the crabs are likely to be at different times of the year.

Providing the fishermen with precise knowledge of where aggregations of the red king crab can be found will help them to harvest this valuable resource more efficiently, with a higher profitability and a lower environmental footprint. Our new findings can hopefully act as a corner piece in the puzzle of understanding the crab in the new waters that it has invaded. From this we can build additional knowledge to support sustainable harvesting and at the same time minimise the crab’s southward colonisation. Because let’s face it: despite its blacklist membership the red king crab is not likely to disappear.

This story is originally published on the website of the Fram Centre