What drives pollutant exposure in Barents Sea polar bears?

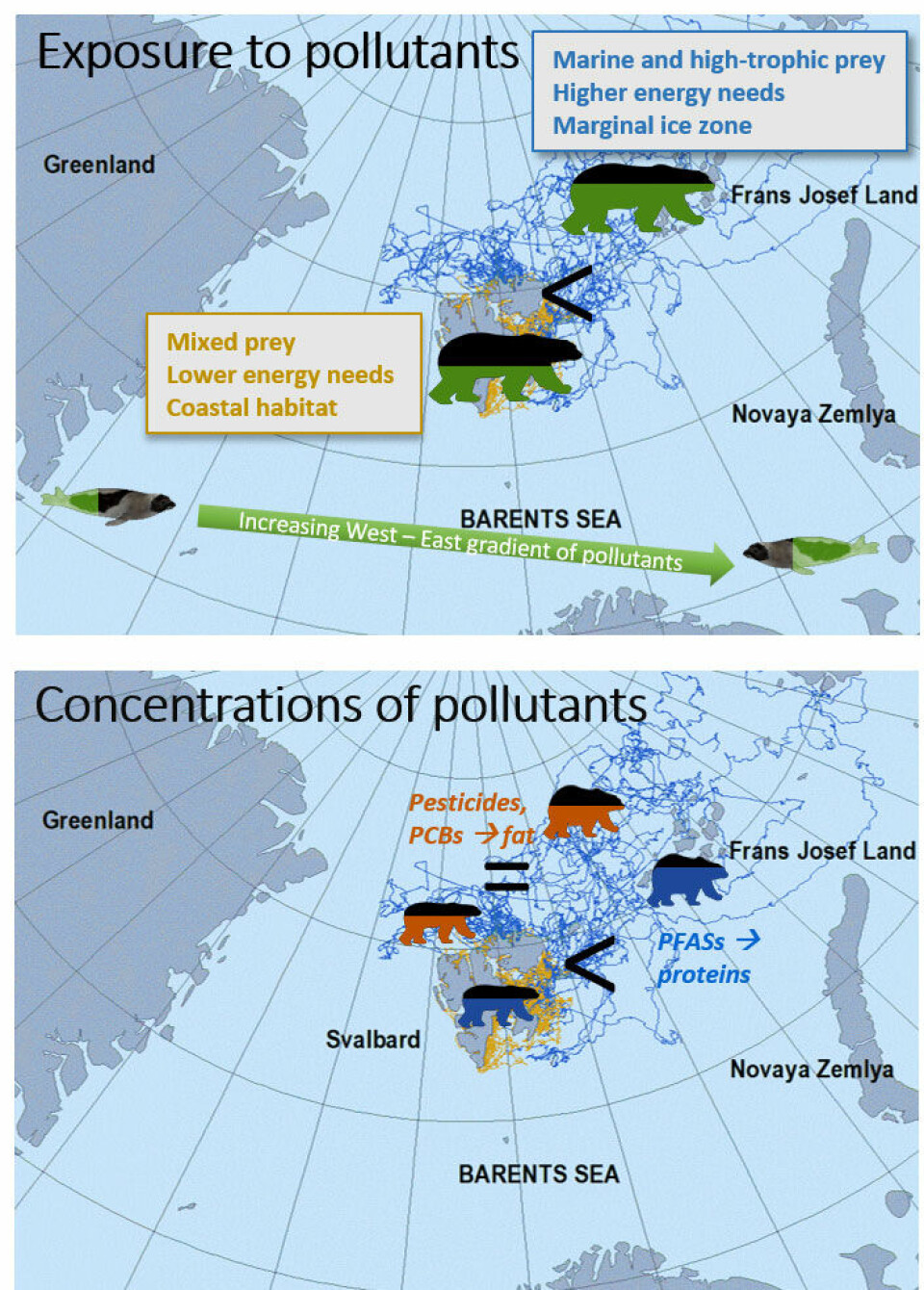

Polar bears in the Barents Sea population use their environment in two different ways. Bears that spend most of their time offshore are exposed to higher levels of pollutants than bears that stay along the coast due to differences in feeding habits, energy expenditure, and geographical distribution.

By: Pierre Blévin*, Jon Aars, Magnus Andersen, Anna Lippold, Sabrina Tartu, Heli Routti // Norwegian Polar Institute, Marie-Anne Blanchet // UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Linda Hanssen and Dorte Herzke // NILU – Norwegian Institute for Air Research

*Currently affiliated with Akvaplan-niva AS

1.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are man-made chemicals. They have been used intensively for numerous agricultural, industrial, and commercial applications and it takes many decades for them to break down in the environment. Atmospheric and ocean currents, as well as river outflows, bring POPs to the Arctic, where they biomagnify in food webs and bioaccumulate in individual animals over a lifetime. Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are top predators of the Arctic ecosystem and can live for up to 30 years. This means they are exposed to relatively high levels of pollutants over a long period of time, which may cause a wide range of adverse health effects.

Polar bears from the Barents Sea have considerably higher concentrations of some pollutants than other subpopulations.

Arctic sea ice, which is the main habitat where polar bears travel, hunt and mate, is declining very fast in the Barents Sea. The loss of sea ice is the greatest threat to polar bears.

It is, therefore, crucial to understand how the combined impacts of habitat loss, pollutant exposure and reduced food availability might affect the bears.

Barents Sea polar bears have two distinct ways of using their environment to cope with the seasonal variation of sea ice extent. “Offshore bears” undertake long annual migrations to follow the sea ice as it retreats into the north-eastern Barents Sea. “Coastal bears” stay close to the Svalbard archipelago in the western part of the Barents Sea year-round using sea ice close to shore and glacier fronts as preferred hunting areas. Sea ice loss due to climate change means that the migration routes of offshore bears are getting longer. Around Svalbard, longer periods with reduced sea ice force coastal bears to feed more on land-based prey. Consequently, in the Barents Sea, offshore and coastal polar bears must cope with very different ecological challenges.

Levels

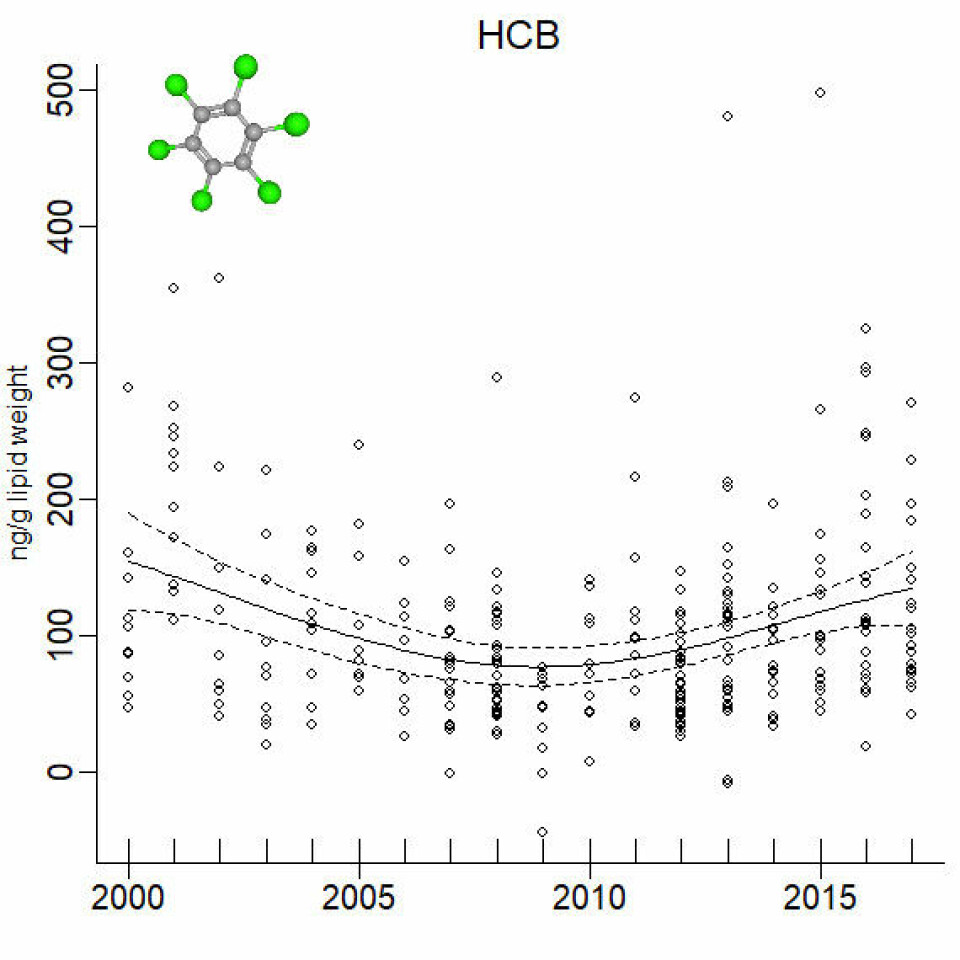

Hexachlorobenzene levels in Barents Sea polar bears from 2000 to 2017. After the implementation of international regulations, the concentrations of several legacy POPs gradually decreased in Barents Sea polar bears. More recently, levels of some POPs have begun to increase again, possibly because they are being re-released from melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost. Hexachlorobenzene is one such pollutant. This graph shows trends over time, adjusted for climate-related variation in the bears’ body condition and feeding habits (adapted, with permission, from Lippold et al 2019, Environmental science & technology, 53(2), 984-995, © 2019 American Chemical Society).

2.

Recent research by the Norwegian Polar Institute and collaborators from other Fram Centre institutes have provided knowledge about ecological drivers of pollutant exposure in Barents Sea polar bears. We have identified three important driving factors: what the bears eat, where they spend their time, and how much energy they use.

- Offshore polar bears are exposed to higher concentrations of pollutants than coastal bears because they feed primarily on marine prey high up in the food web (e.g. seals). Coastal bears rely on a mixed diet including land-based prey (e.g. seabird eggs, reindeer).

- Offshore polar bears are distributed further north and east than coastal polar bears, preferentially in the transition zone between the open ocean and sea ice (the marginal ice zone). Farther north, the uptake of pollutants released from melting ice and snow during peak spring plankton blooms leads to high concentrations in the food web. Farther east, the bears’ prey is more polluted, probably owing to proximity to pollutant emission sources and transport pathways.

- Offshore polar bears have higher energy expenditure because they spend more time reaching their foraging habitat and because they hunt for seals over larger areas. Coastal bears live in more restricted areas and feed opportunistically on whatever is available locally. Consequently, offshore bears need more energy, eat more food, and hence assimilate more pollutants than coastal bears.

Despite these differences in exposure, only one type of studied pollutants is currently higher in the blood plasma of offshore bears: perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). PFASs bind to proteins in blood and liver, whereas other POPs, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlorinated pesticides, are stored in fatty tissues. Concentrations of pollutants that accumulate in fatty tissues are similar in offshore and coastal bears. This is because offshore bears are fatter than coastal bears, and pollutants that bind to fat are more diluted in fat bears than in thin coastal bears.

The use and production of the so-called “legacy” POPs have long been banned or restricted by international regulations such as the Stockholm Convention. In response, Barents Sea polar bears’ exposure to legacy POPs has generally decreased over the past 20 years. Nonetheless, levels of some compounds have been increasing during the last decade in Barents Sea polar bears. This can probably be attributed to the re-emission of pollutants from melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost.

This article is originally published in the Fram Forum