Partner story

Using community science to gain holistic understanding of climate change

Understanding and adapting to environments that are now changing within a single lifetime requires more than natural scientific methods, because traditional scientific monitoring often misses the nuanced experiences of local communities. We have probed the rich local knowledge of Svalbard residents.

By: Ann Eileen Lennert, Espen Viklem Eidum and Linn Bruholt // UiT – The Arctic University of Norway

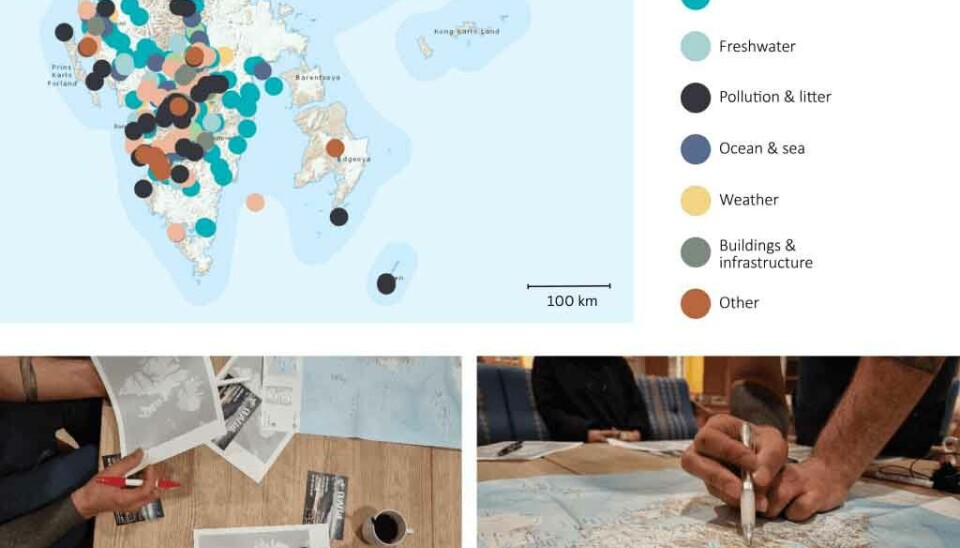

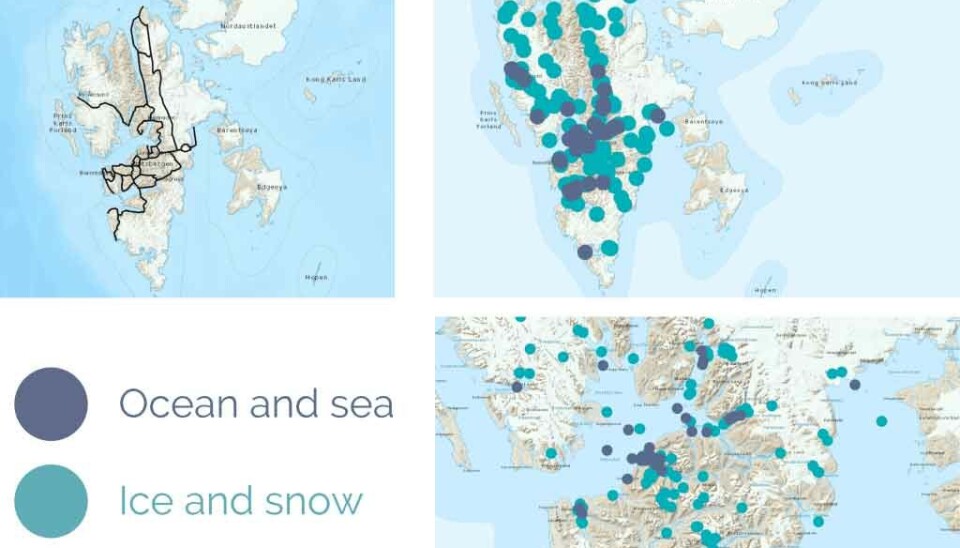

The SVALUR and Catchment 2 Coast projects stress the importance of combining various community science methods and therefore included surveys, focus groups, interviews, and cognitive mapping, resulting in 750 observations across the entire Svalbard archipelago. These observations, both real-time and historical, provided deep insights into environmental changes. Multifaceted and relational, they complemented scientific data with a more holistic understanding of the changes.

The coastline is in constant change. Every time I go kayaking it has changed.”

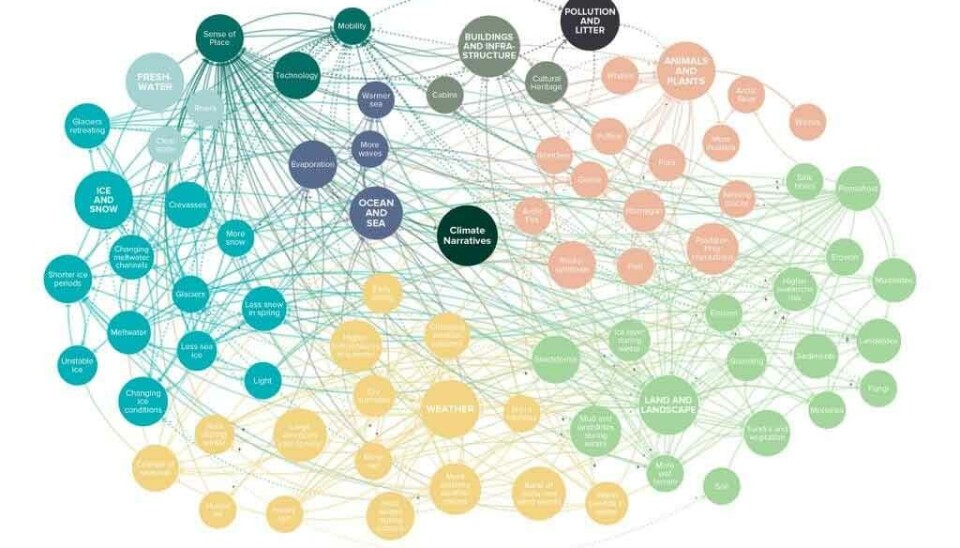

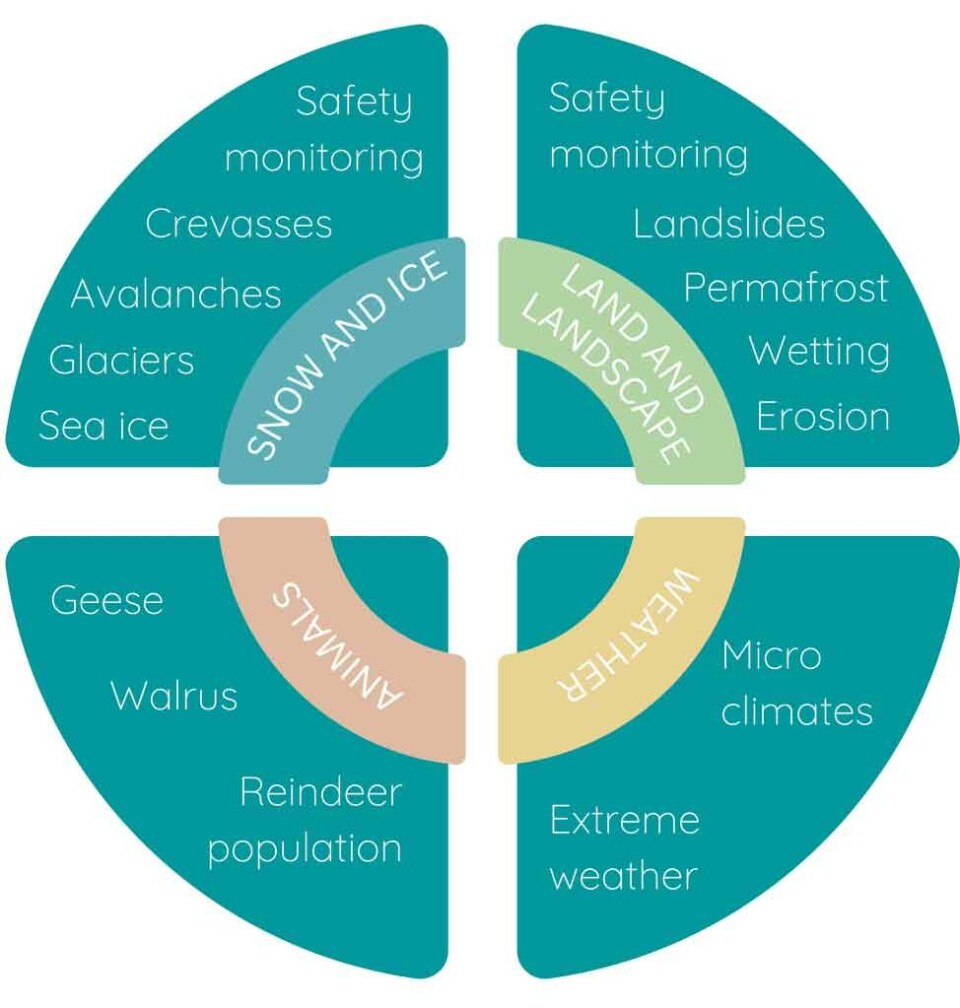

Using Maptionnaire, an online map-based platform that allows ordinary citizens to share their knowledge, Svalbard residents made observations about altered seasons, wetter climate and environment, permafrost thawing and disruption, microclimates, changes in animal species and distribution, sea ice and crevasses. They reflected on their movements, safety, winter travel routes that change from day to day, or shared personal reflections on how the landscape has changed. The knowledge they shared linked weather, ecosystems, fauna and landscape together holistically, through experiences.

The air feels different. Before it was more dry, now it smells different.”

The observations also revealed a network of routes that illustrate infrastructure and geographical opportunities that can contribute as resources for natural scientific endeavours. These networks of observations can also help identify important monitoring needs in the context of transport, safety and well-being.

The glacier here has changed significantly in the last 10 years. And we must constantly look for new ways to travel in this area.”

Not least, the study prompted us to examine our role as researchers, to ask ourselves if the monitoring and research done in Svalbard is visible, accessible, and relevant to its residents, and whether it meets the needs they identify, especially in regard to safety and mobility.

Yet, we believe that there are great opportunities to increase the relevance and inclusion of community science in long-term monitoring of environmental changes. Holistic insights and observations can offer a unique way to fill the many knowledge gaps that exist in today’s long-term monitoring while also making monitoring relevant and meaningful for the local community.

The glacier that led into the river has receded so much that the river no longer flows into the lake. Which means that char there has become stationary as it cannot get from the lake back to the sea.”