Russia’s coronavirus recovery plan has no space for renewables

ADVERTISEMENT

Text: Jake Cordell

One of the first wind power stations in Russia sits on the Commander Islands — a group of scrubby, sparsely inhabited mountainous rocks 100 miles off the country’s eastern coast in the Bering Sea.

Started with a donation of two turbines from Denmark in the 1990s, the mini wind farm was designed to halve the 700 islanders’ reliance on diesel to generate their electricity. Given frequent storms and irregular travel connections, the dirty fuel can cost twice as much as on the mainland.

When Georgy Safanov, director of the Center for Environment and Natural Resource Economics at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics recently visited the islands he noticed that only one of the four wind turbines was in operation. The next day, the situation was the same — with a different turbine spinning but the other three switched off.

“I asked the locals, ‘Why aren’t you using them? They are here, that’s free energy for you,’” Safanov told The Moscow Times.

The answer, he said, gives a blunt insight into Russia’s approach to renewable energy.

“They replied, ‘We could use them all, but we still have a diesel power generator. And that’s owned by guys who are close to our village administration.’”

“Russia has huge, huge potential for renewables, everywhere and in everything — solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, biofuels. But the economics around the energy system are very traditional and corrupt,” Safanov said, adding that he believes these problems are stunting Russia’s renewables industry.

Unrealized potential

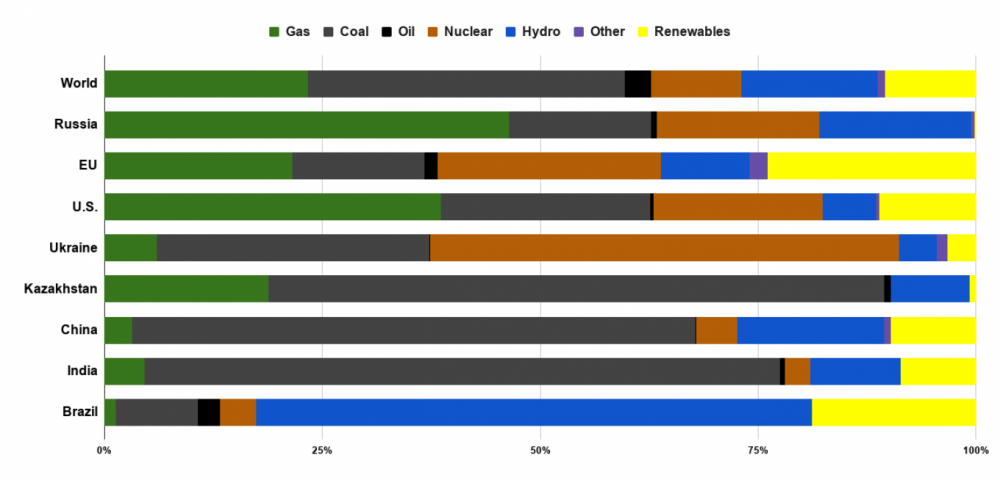

Only 0.16% of Russia’s electricity was generated from renewable sources in 2019, according to the BP statistical review of world energy. The world average is more than 10%, and in Europe it is around 20%. While Russia stands fourth in the world for overall electricity generation, it is ranked 109th for renewables.

Analysts and industry figures say the situation in Russia is unlikely to change as it comes out of the coronavirus pandemic, despite some of the world’s largest economies allocating substantial extra cash to fight climate change and accelerate decarbonization.

“In Europe, crisis response plans have renewable energy and climate projects in first place. In ours … we don’t see any ambitious plans to restart the Russian economy using carbon-free technologies or by investing into carbon-free projects,” said Alexey Zhikharev, director of the Association for the Development of Renewable Energy (RREDA).

Despite a Kremlin target to generate 4.5% of Russia’s electricity from renewable sources by 2024, Zhikharev says even if every project currently in development comes online in time, the best-case scenario will be 1%.

“Medium-term plans for [renewables] capacity are at a very low level — even compared to our neighbors like Ukraine, Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan, without considering China or the U.S.,” Zhikharev added, pointing out that China commissions 100 times more capacity per year in new renewable energy projects than Russia.

The Kremlin’s latest energy strategy, in force from June and running until 2035, makes little mention of renewables or a transition to clean energy, said Maria Shagina, a researcher who focuses on Russia’s energy sector. It even pencils in higher investment in coal projects — seen by many as the dirtiest kind of fossil fuel. When Russia talks of energy diversification or an energy transition, it usually means balancing export markets for vital multi-billion dollar oil and gas exports, she added.

“The strategy is definitely one, if not two steps behind what’s happening. And the pandemic has compounded that and made it even worse,” Shagina said.

Completely unprepared

Russia is “completely unprepared,” for a world moving away from hydrocarbons and becoming more and more committed to tackling climate change, said Tatiana Mitrova, director of the Skolkovo Energy Center.

“The Russian government is… very sceptical concerning the anthropogenic nature of climate change,” she told The Moscow Times. This leads to a passive, box-ticking approach to green initiatives — such as Russia’s belated ratification of the Paris Climate Accords, when the Kremlin eventually signed up, but chose a baseline emissions level so high that it requires practically no effort to ensure compliance.

Mitrova is among those pushing the Russian government to incentivize renewables and make the economy more green.

“We should use this period when the state will be launching stimulus packages to push economic growth, to use at least some part of it for green technologies.”

But a detailed package of green proposals put to the Russian government over the last few months wasn’t met with enthusiasm. Analysts say the state’s capacity for supporting the energy industry is dominated by big ticket or geopolitical projects like the OPEC+ agreement, tax breaks for Arctic oil or LNG projects and flagship pipelines like Nord Stream 2 to Europe and the Power of Siberia to China.

This article first appeared in The Moscow Times and is republished in a sharing partnership with the Barents Observer.