Environmentalists point the finger of blame at Mayak, the plant to process Kola’s Cold War legacy

A mysterious cloud of radioactive ruthenium-106 blowing over Europe earlier this autumn triggered many speculations about Russia trying to ‘cover-up’ a leak from the country’s largest nuclear waste treatment facility.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Traces of radiation was first detected and made public by French and German authorities who measured the isotop in the end of September and beginning of October. Soon, ruthenium-106 was found at monitors in at least fourteen European countries, including Norway. The measurements, though, showed very low levels and caused no health risks for the people. As the isotope is not normally detected in the air, its presence can only be linked to an uncontrolled release.

French Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN) says the absence of any other artificial radionuclide rules out the possibility of a release from a nuclear reactor, hence pointing to a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing activity or the production of radioactive source. Such isotope source, again, is used in medical treatment or for radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) which powers satellites or navigation lighthouses. The French nuclear watchdog, IRSN, has carried out simulations based on measurements from 400 sites across Europe trying to locate the release zone. Without being able to specify the exact location, the institute do point to the most plausible location of the leak to be between Volga and the South-Urals. IRSN estimates the leak to be between 100 and 300 teraBecquerels.

The only reprocessing plant for spent nuclear fuel in the area is Mayak, just north of Chelyabinsk.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Rosatom denies responsibility

Rosatom, Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation who operates the plants in Mayak, has categorically denied any responsibility for the leak. In a first statement, Rosatom points to Slovakia and Romania saying «extremely high concentrations of Ru-106 in the atmosphere were recorded in Slovakia (29.-30.09.2017) and in Romania (September 30, 2017).»

The possible ‘cover-up’ could have worked wasn’t it for Russia’s own agency responsible for radiation monitoring, Roshydromet, last week published a report revealing measurements in September of «extremely high» levels of ruthenium-106 at two monitoring stations near Mayak. The report reads that the two stations in the towns of Argayash and Novogorny detected levels respectively 986 and 440 times higher than the previous month. The two towns are located less than 100 kilometers from Mayak.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Nadezhda Kutepova a local environmentalists from the closed city of Ozyorsk near Mayak who was forced to flee Russia in 2015, now reveals more inside information. Kutepova says Mayak was testing new equipment on September 25 and 26 at the reprocessing plant and that something abnormal may have happened.

«Emission of ruthenium may come from the reprocessing plant 235 or RT-1 in Mayak where the vitrification plant for very high-level nuclear waste is located,» Kutepova tells. She points to the new vitrification furnace which started operation last December and experienced problems during construction and testing. «My idea is that the furnace was built with a lot of problems that emerge in the operation and I think this is the cause of the ruthenium-106 leak we saw in September,» she explains. Mayak has loads of high-level liquid radioactive waste that needs to be stabilized and made safer and starting the new plant was, according to Kutepova, rather urgent. She calls the equipment bought for the electric furnace «low-quality».

By-product from vitrification process

Before fleeing Russia, Nadezhda Kutepova worked as a lawyer and headed the NGO Planeta Nadezhd (Planet of Hopes) that worked in the closed nuclear city of Ozyorsk (formerly known under the secret postal code name Chelyabinsk-65). First, her group was declared «foreign agent» by the Justice Ministry. Recently afterwards, she was accused on federal TV of conducting industrial espionage. Then she decided to leave the country.

Russia has been using vitrification technology to make liquified nuclear waste from its reprocessing facilities into solid glas since 1987. Ruthenium-106 is a by-product from this process occurring in the form of gas due to the high temperature in the process.

At the reprocessing plant in Mayak, spent nuclear fuel from Russia’s and some eastern European nuclear power plants are reprocessed. So are spent nuclear fuel from the military fleet of reactor-powered submarines and the Murmansk-based fleet of civilian nuclear-powered icebreakers. Additionally, Mayak has received all the RTGs collected with Norwegian funding from the European part of Russia’s Arctic coast. The first containers with spent nuclear fuel from from the rundown storage site in Andreeva Bay on the Kola Peninsula were sent to Mayak earlier this year and thousands of more fuel elements are soon to take the same direction. For Norway, who’s foreign minister was present when the first shipment left Andreeva Bay in June this year, Mayak is seen as part of the solution to get rid of a potential radiation hazard in its northern neighborhood.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Norway must take responsibility

Speaking to the Barents Observer from Paris, Nadezhda Kutepova says Norway now should initiate an international investigation into what happens in Mayak.

«Norway could demand to create an international investigation group which must include specialists from states and NGOs who received the radiation cloud. This group must have the right to visit Mayak and sites around that are contaminated. Soil myst be analyzed as soon as possible,» Kutepova says. «Secondly, Norway can demand guarantees that spent nuclear fuel which is transported from the Murmansk region is not reprocessed, but treated and kept safe the way they are.»

Nils Bøhmer, a nuclear physicist with the Bellona Foundation, agrees with Kutepova and says Norway has to take a special responsibility in order to make sure no radiation hazards happens with nuclear waste transported to Mayak with Norwegian funding.

«The leakage of radioactive ruthenium this autumn can not be linked directly to the waste transported from Andreeva Bay earlier this year. Ruthenium-106 has a half-life of about a year, so spent nuclear fuel older than 10 years contain very little of the isotope,» Bøhmer explains. However, he pinpoints, «the vitrification facility could have been treating waste from the icebreaker fleet, which spent nuclear fuel is transported to Mayak with special designed rail wagons paid by Norway in the 90ties.»

Not in My Backyard

In a 2005-report (pdf), Norway brags about the project: «In order to avoid accumulating spent nuclear fuel on the Kola Peninsula, Norway has funded the construction of four specially designed goods wagons to transport spent nuclear fuel to Mayak PA for final treatment and storage.»

«Secondly,» Bøhmer argues, «when we know that the reprocessing- and vitrification plants in Mayak are the very same to treat the nearly twenty thousands spent uranium assemblies from Andreeva Bay, alarm bells should be triggered when we learn about such malfunctions as this.»

Nils Bøhmer is also very critical to Russian authorities’s lack of information regarding possible leakages from Mayak and insight into the safety accords of the plants.

«Norwegian authorities must act and take responsibility. Otherwise, we can’t say that Norwegian sponsored projects in the Murmansk region are purely for eliminating nuclear safety risks. Out of sight, doesn’t mean out of mind,» Nils Bøhmer says with a serious face.

Notification agreement recently signed

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Norwegian Radiation Protection Authorities (NRPA), who manages the nuclear safety cooperation with Russia on behalf of Norway’s Foreign Ministry, expects Russia to inform when incidents happens.

In an e-mail to the Barents Observer, Director of Legal Affairs Kristin Elise Frogg, says «the Norwegian side will always want to be alarmed or notified about incidents in our neighboring countries, and when several countries make measurements of releases like in this case it will always be of interest to map what could be the source of the release.»

After years of negotiations, Norway and Russia in 2015 signed a protocol on early notification of nuclear accidents and exchange of information on nuclear facilities. The agreement, though, covers installations within a 300-kilometer area from Russia’s border to Norway. Mayak is way further east.

«We […] expect Russia to inform us if there is an accident in Russia even if this should happen outside the geographical area of the agreement of notifications. That is also in line with IAEA’s Convention on Early Notifications [of Nuclear Accidents],» says Kristin Elise Frogg.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

NRPA has exchanged measurement data on ruthenium-106 when the isotope first was detected. «Based on this, we have sent a formal inquiry to Rosatom requesting more information,» Kristin Elise Frogg elaborates. She, however, underlines that Rosatom still claims that the release is not coming from any Russian facilities.

Russia welcomes investigation

This week, Rosatom, announced it will set up a commission to find out what could be the source of the ruthenium-106 cloud detected by European and Russian monitoring systems.

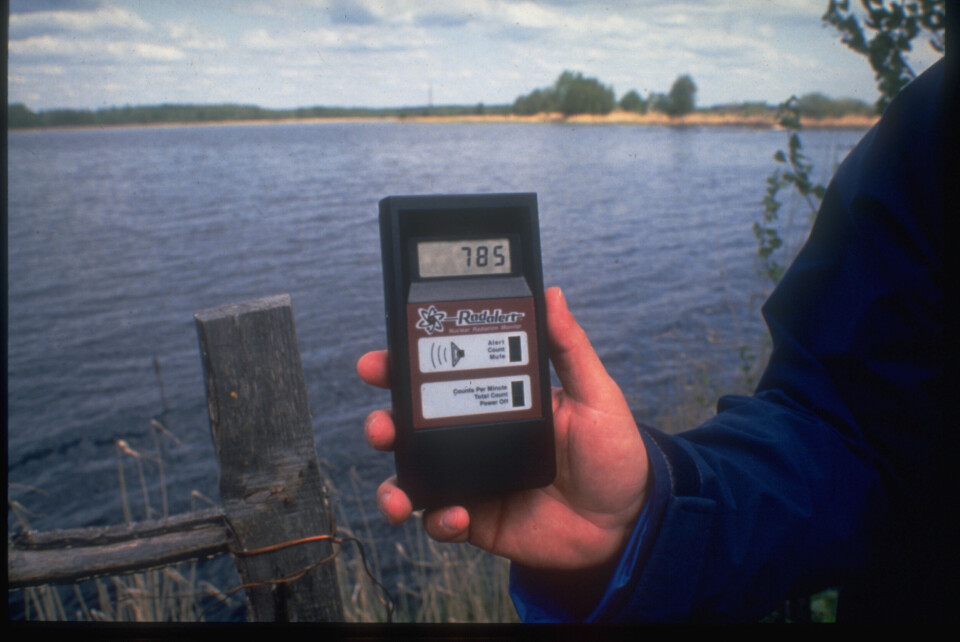

«We welcome this initiative,» says Frogg. She tells that Norwegian authorities has made it clear that it is of interest to relaunch a possible cooperation and dialog about the environmental situation in Mayak. «This was discussed at a meeting in St. Petersburg in October.» In the 1990s, Norwegian and Russian experts worked together on analyzing samples of soil and water from the reservoirs near Mayak in the South-Urals.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Bad safety record

Mayak has a bad record of nuclear accidents. Built just after World War II, the site produced the plutonium to Josef Stalin’s first nuclear bomb that was exploded in 1949. Those days, radioactive waste were dumped into reservoirs leaking into the nearby Techa River where local villagers had no clue about being exposed to dangerous doses of radiation. In 1957, a tank filled with liquid high-level radioactive waste exploded and contaminated a huge area including many towns. Soviet authorities covered-up the accident that first decades later became known to have been one of the world’s most serious nuclear disasters. In 1967, the Lake Karachai where Mayak had dumped deadly radioactive waste from the nuclear weapons production, dried up and radioactive dust was spread by the wind over another area outside the plant’s fences.

«What is most worrying,» Bellona’s Nils Bøhmer says «is to see how Russia continues the pattern from the Soviet times when covering-up incidents seems more important than protecting the population from leakages of radioactivity.»

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

State Duma Deputy Maksin Shingarkin, who sits in the parliament’s committee on environment and natural resources, blamed an American spy satellite for being the source of the ruthenium-106 contamination saying it had cruised over Russia and Europe and showered the radioactive isotope along the way.

Similar incident in France in 2001

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Rashid Alimov, Senior Nuclear Campaigner with Greenpeace Russia, also believes the vitrification plant in Mayak is to blame.

«We think that it’s a most possible explanation that the ruthenium-106 discharge came from the vitrification plant in Mayak, especially taking into account similar incidents at vitrification in Le Hague,» he says to the Barents Observer from Moscow.

Le Hague is the reprocessing plant in France which in 2001 had a incident during vitrification causing contamination of radioactive ruthenium-106. Details about the incident was reported by IAEA.

«There can be other versions too, and we think it’s important that the release is investigated.» Alimov says and continues: «Regretfully in Russian nuclear industry there are traditions of covering up incidents.» He points to the 1957 Mayak accident, the 1986 Chernobyl cover-up and a release of radionuclides from the Siberian Chemical Combine near Tomsk in 1993 where authorities delayed information to the public.

You can help us…

…. we hope you enjoyed reading this article. Unlike many others, the Barents Observer has no paywall. We want to keep our journalism open to everyone, including to our Russian readers. The Independent Barents Observer is a journalist-owned newspaper. It takes a lot of hard work and money to produce. But, we strongly believe our bilingual reporting makes a difference in the north. We therefore got a small favor to ask; make a contribution to our work.