Norway well prepared to meet Russian jamming

The loss of GPS signal for commercial aircrafts over Eastern Finnmark during Russia’s large-scale military drill Zapad-2017 came as no surprise, says Defense Minister Frank Bakke-Jensen.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 13.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

For about a week in September, SAS and Widerøe flying to airports in the high north of Norway had in periods to navigate with the help of radio signals due to loss of GPS. Especially over eastern Finnmark, but also all the way west to Alta airport, some 250 kilometers west of the border to Russia, NRK reported at the time.

Speaking about the issue with the Barents Observer, Minister of Defense Frank Bakke-Jensen says he is not surprised that Russian jamming can influence activities on the Norwegian side of the border. «This is a very concrete example. It was a large military exercise by a big neighbor and it influenced civilian activities like air traffic and the fisheries.» Aircrafts and fishing vessels use GPS for navigation.

Defense Minister Bakke-Jensen, though, admits that jamming in this scale has never happened before. He says Norway’s protection against GPS jamming «is to have alternative ways to navigate.» Bakke-Jensen says parallel system, alternative ways of navigating is a part of Norway’s security.

Jamming aimed at Russia’s own forces

Head of Norway’s military intelligence, Morten Haga Lunde, confirms in an interview with Aftenposten Russia’s jamming during Zapad-2017. «GPS jamming was practiced, electronic warfare. Most likely, this jamming was aimed at interfering Russia’s own forces’ use of GPS. A side-effect, however, affected Widerøe and intercontinental flights that Russia should have seen coming.» In Finnmark, regional airliner Widerøe has commercial daily flights to 11 airports, while SAS flies to Alta and Kirkenes.

Barents Sea

It is said that a one-kilowatt portable jammer can block a GPS receiver from as far away as 80 kilometers. Russia’s Arctic 200th Independent Motor Rifle Brigde in Pechenga is 55 kilometers from Kirkenes airport. The Kola Peninsula is home to many other military camps and naval bases. Norwegian Communication Authority made measurements from helicopters flying out of Kirkenes at the time when the GPS signal was lost trying to understand the scoop problem. The sources of the p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}disruptions were clearly coming from the east. The jamming, though, didn’t caused problems on ground. What happened at sea is unclear.

Head of Communication with the intelligence service, Kim Alexander Gulbrandsen, does not answer the question from the Barents Observer regarding possible Russian jamming before or after the September military drill affecting GPS receivers in the Barents Sea.

In August this year, reports came suggesting that Russia may had tested a new system for spoofing GPS, causing navigation problems for 20 ships in the Black Sea. Spoofing GPS signal means a captain on the bridge could be mislead to believe his vessel is somewhere else than it actually is. Just like in the James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies where a British Frigate is fooled by a spoofing attack in the South China Sea.

Mobile signals blocked in Lativa

Russia’s use of electronic warfare, aimed at shutting down communications and navigation signals is well known from the war in eastern Ukraine. In September, the British military magazine Jane’s quoted Ukrainian Major General Borys Kremenetskyi saying they had identified more than a dozen types of Russian electronic warfare equipment in use in the Donbas region since the conflict started in 2014. Electronic warfare operations allegedly originated from both inside separatist-held territory and from the Russian side of the border.

Two weeks before exercise Zapad (translated West), the mobile phone network in Latvia experienced a major outage, the Washington Post reported. A 16-hour outage of the country’s emergency phone centre came at the time of Russia’s military drill.

John-Eivind Velure with the Norwegian Communication Authority, safeguarding the mobile phone network, says in an e-mail to the Barents Observer that no disturbances on the mobile phone network have been tracked down to any proven jamming in Norway’s border area to Russia.

«We have no indications that the mobile phone network in eastern Finnmark is more or less vulnerable or robust against jamming than mobile networks elsewhere,» Johan-Eivind Velure explains. He elaborates and tells that a challenge, however, is how jamming easier could take-out the mobile network in an area we few, or only one, base station. Along the Norwegian-Russian border both countries have several base stations close to the border line, like the one at Borisoglebsk which periodically sends signals towards the Kirkenes harbor area.

Emergency communication network

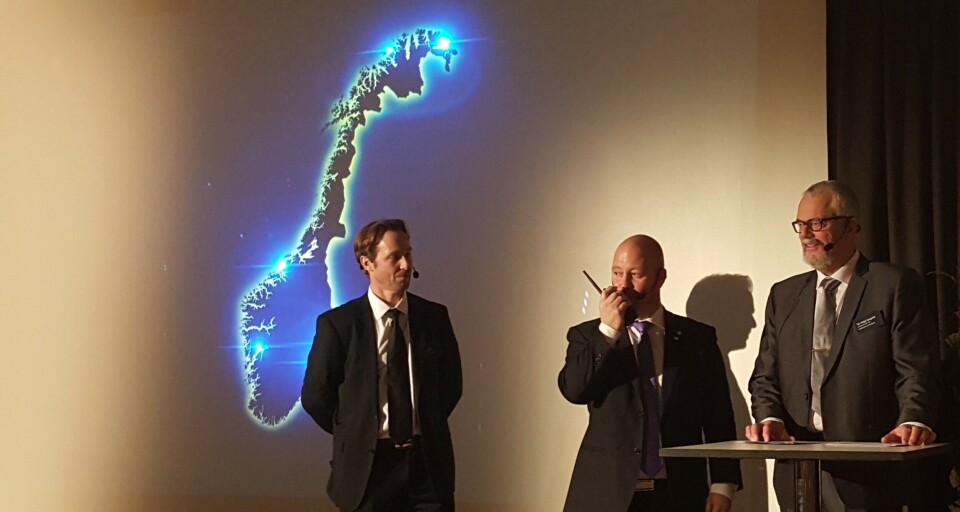

Two years ago, Norway’s King Harald and Minister of Justice and Public Service, Anders Anundsen, officially opened the country’s new digital emergency communication network at an event in Kirkenes. The network helps different response teams, like fire brigades and police, to communicate in case of emergencies.

Head of Police in Finnmark, Ellen Katrine Hætta says all electronic communications are vulnerable for jamming, but underlines «we have no special worries because of our location, this is something we consider could happen anywhere.» The police p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}headquarters command centre for Finnmark is located less than eight kilometers from the Russian border.

«Jamming is today possible with very simple means,» she says and explains that the police has several other ways to communicate and navigate «it’s not unilaterally based on GPS systems.»

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

«Significant capability»

Speaking to Reuters about practicing electronic warfare during Zapad-2017, U.S. Army Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, said Russia has developed «a significant electronic warfare capability» over the past three years.

Russia’s Ministry of Defense has by two occasions after Zapad-2017 posted information about exercising the country’s electronic warfare capabilities. In late October, a drill took place in the Khabarovks region aimed to repel an attach by a sabotage and reconnaissance group. Use of mobile electronic warfare systems were used to defeat mobile communication signals. A week later, 1,000 troopers were called in for training to become electronic warfare specialists before being sent to different military units as operators.

The Defense Ministry said «more than 40 types of electronic warfare equipment and control systems» would be used.

New Army unit on border to Russia

Well aware of Russia’s electronic warfare capabilities, Defense Minister Frank Bakke-Jensen, says he does not consider Russia as «a primary threat against Norway» but he points to «a more tense security situation in the world» when explaining why the country soon will base additional 200 soldiers on the border to Russia.

Bakke-Jensen visited the Garrison of Sør-Varanger this week. Here, both the new 200-soldiers strong Army unit and the military border guards working under command of the police to secure the border to Russia are based.

You can help us…

…. we hope you enjoyed reading this article. Unlike many others, the Barents Observer has no paywall. We want to keep our journalism open to everyone, including to our Russian readers. The Independent Barents Observer is a journalist-owned newspaper. It takes a lot of hard work and money to produce. But, we strongly believe our bilingual reporting makes a difference in the north. We therefore got a small favor to ask; make a contribution to our work.