GUGI closes inlet to Olenya spy-sub base with floating barrier

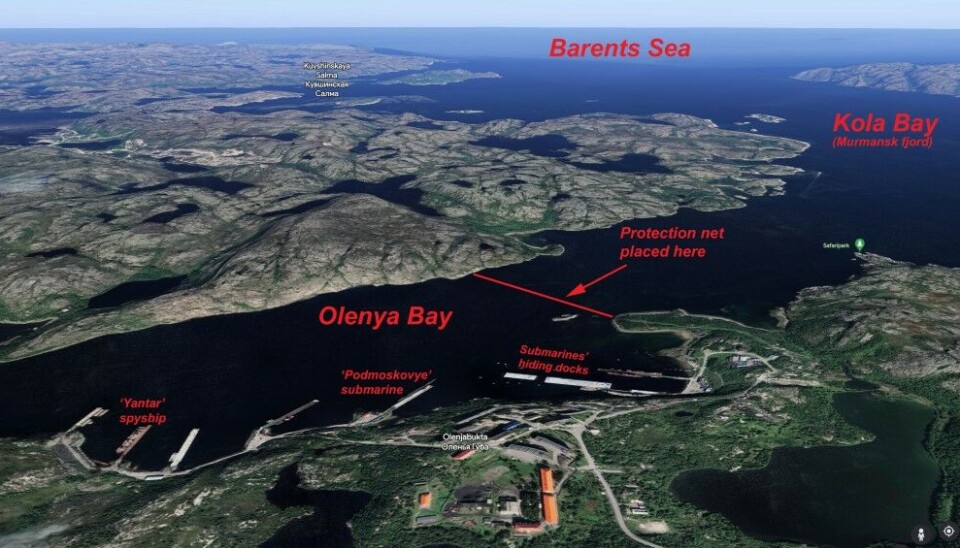

New satellite images this June show what appears to be a boom net barrier stretching from shore to shore across Olenya Bay, home to Russia’s top-secret special mission submarines.

It is new and never seen before at any of the Northern Fleet’s submarine bases along the coast of the Barents Sea.

By emplacing a floating boom net, the entrance to the important GUGI base in Olenya Bay north of Murmansk is partly protected against small drone attacks or enemy submarines on sabotage or espionage missions.The net goes from surface to seafloor and can both hold sensors and mines, in addition to serve as a physical underwater fence.

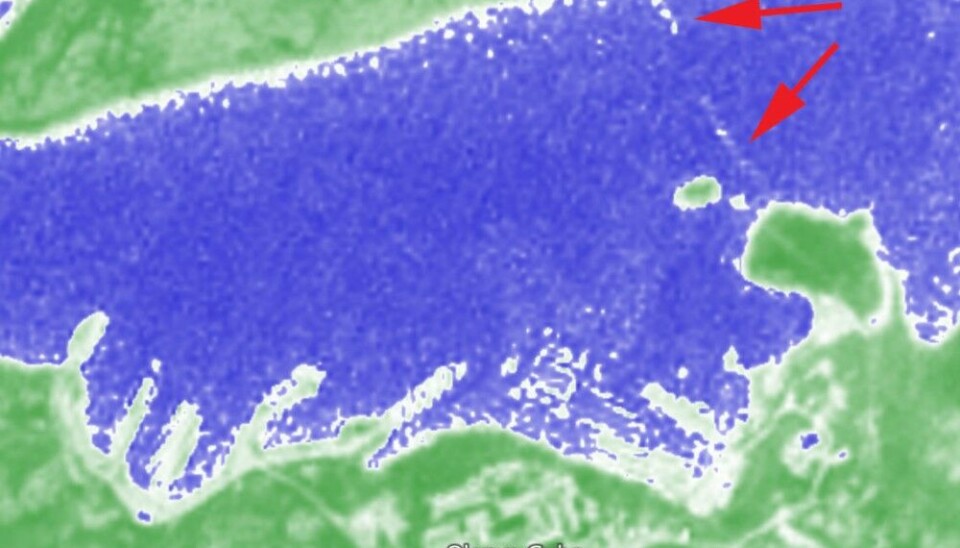

An image downloaded by the Barents Observer and taken by the European Union Space Program’s Sentinel-2 satellite from June 11 shows the new barrier. Although the resolution is low, the cross-bay net is clearly detectable.

By using the satellite service’s pixel option to see the difference between water and non-water, the contour of the protection net is clear. It looks like there is an opening mid-sea, either to let boats and submarines sailing to and from the base through or because parts of the net is somewhat deeper in the sea at the time the image was captured.

Similar in Sevastopol

After Ukrainian maritime drones attacked the Black Sea fleet’s naval base in Sevastopol last year, similar protection booms on the water were put in place. Also, Russia’s naval port near Novorossiysk has got floating protection layers.

It was a Norwegian military analyst with the tweeter account The Lookout who was first to discover the new net in Olenya Bay based on a June 4 satellite image.

H I Sutton, a British submarine expert, says the positioning of the net across the entrance to Olenya Bay “is significant” as the base is very unlike the other submarine bases on the Kola Peninsula.

“It is clear that it is a defense,” he writes in an article for Naval News. “It is not the type used to contain pollution or some other prosaic explanations,” he argues and concludes: “Russia is hardening its key base in the Arctic.”

Whether or not the protection net is created to protect against incoming sabotage drones or aimed to stop US Navy reconnaissance underwater vehicles sailing in from a mothership in the Barents Sea, is unknown. The Russian defense establishment never answers questions from the Barents Observer.

Secret seabed operations

The boom net can easily be moved by the staff in Olenya when their own vessels, or vessels bound for the Nerpa shipyard deeper into the bay, sail in or out.

Olenya is home to Russia’s spy submarines operated by GUGI, the Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research under the Armed Forces.

With deep-diving nuclear-powered subs, the missions are often top secret. One of the subs sailing for GUGI from Olenya was the ill-fated Losharik. Conducting seafloor work in the Motovsky fjord in 2019, the submarine caught fire and the entire crew of 14 officers were killed.

Olenya is also homeport for the “Yantar” a modern special survey surface ship used by GUGI to map gas pipelines in the North Sea and Trans-Atlantic internet cables. The ship carries a deep-diving submarine, drones and sonar systems. Often when sailing, the “Yantar” turns off its AIS tracking system, making it difficult to monitor movements and whereabouts.

In a previous article, the Barents Observer detailed how Russian spy ships have increased activities around global data cables with assets from the Olenya Base on the Kola Peninsula.

Pushing fear

Attempting to create an atmosphere of fear, the Kremlin regularly hints to the West about the vulnerability of seafloor infrastructure.

On Wednesday this week, Russia’s Deputy head of the Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, wrote on Telegram that there are no longer any moral restrictions left “to prevent us from destroying cables of communications of our enemies, laid along the seafloor.”

Medvedev has over the last years become a key hardline propaganda voice for the Kremlin, says Eskil Grendahl Sivertsen, a Norwegian expert on Russia’s cognitive warfare and influence operations.

Being a close ally of Vladimir Putin, Medvedev’s threats to attack subsea data cables triggered headlines in Europe and North America.

“From his current position, Medvedev frequently employs aggressive anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric in support of Russia’s brutal and illegal war against Ukraine,” Sivertsen says to the Barents Observer.

“It is not surprising that his often threatening statements attract media attention in the West, which again is amplified on social media. As such, he plays a role in Russia’s propaganda machinery aimed at intimidating, confusing and inducing fear in Western audiences.”

Eskil Grendahl Sivertsen works with the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment (FFI).