"High time to scrap self-imposed restrictions," says former Norwegian Commander. This week's flight map shows why

ADVERTISEMENT

“We need a totally new Russia strategy. My advice is for Norway to scrap both the base policy and self-imposed restrictions,” former Chief of the Joint Headquarters, Lieutenant General Rune Jakobsen said in a debate at Arendalsuka last week, as reported by VG.

“We need to send stronger signals to Russia, to avoid being exposed to hybrid operations in an area where we are very vulnerable,” he said.

Set during the Cold War, the regulations were aimed at not provoking the Soviet Union, which based its fleet of nuclear submarines on the coast of the Kola Peninsula from the early 1960s. For Norway, in those days the only NATO member in Europe with a direct land border with the USSR, the guiding policy was to balance between deterrence and reassurance. NATO membership is the pillar of deterrence and limited military and allied operations near the eastern border are the reassurance.

Winds of change

“Given the current state of affairs, the most important issue is not to restrict allied military activity near Russia, but to ensure that the Russian military stay on their side of the border,” says Per Erik Solli, a Defense analyst with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

He says the restrictions had a secondary domestic agenda “to appease the left-wing political fraction in Norway.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Solli notes that Moscow never reciprocated with a similar regime of restrictions.

“Instead they have during the Cold War, and also recently, regularly arranged military exercises outside Norway all the way down to UK, and even flown mock attacks against targets in Norway.”

Per Erik Solli says Norway is now in a totally new situation.

“The interventions into Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 were wake-up calls, but the shakeup in international relations occurred with the full-fledged brutal Russian war against Ukraine from 2022.”

Kola - Russia’s military powerbank

The Northern Fleet’s ballistic missile submarines based on the coast of the Barents Sea form a key leg in Russia’s nuclear deterrence. Test launches of Bulava missiles, as well as non-functional nuclear-powered weapons like the Burevestnik and Poseidon, are of interest for Western military observers.

Land forces from the Pechenga region next to the border with Norway and Finland have been active in Eastern Ukraine since Vladimir Putin ordered the first militaryish operations in 2014.

The importance of the Kola Peninsula in Russia’s war on Ukraine became even higher on Saturday as the air force in a panic move relocated at least six Tu-22M3 bombers to Olenya air base south of Murmansk after a drone attack on Soltsy-2 air base in Novgorod region took out one of the planes. More than ten Tu-160 and Tu-95 strategic bombers were last fall moved to Olenya. Also that after Ukrainian drone attacks at southern air bases.

From here, inside the Arctic Circle, the bombers regularly flies missions launching cruise missiles against civilian targets in Ukraine.

No strange NATO has a renewed interest in military movements on and near the Kola Peninsula.

Surveillance flights north and south of Finnmark

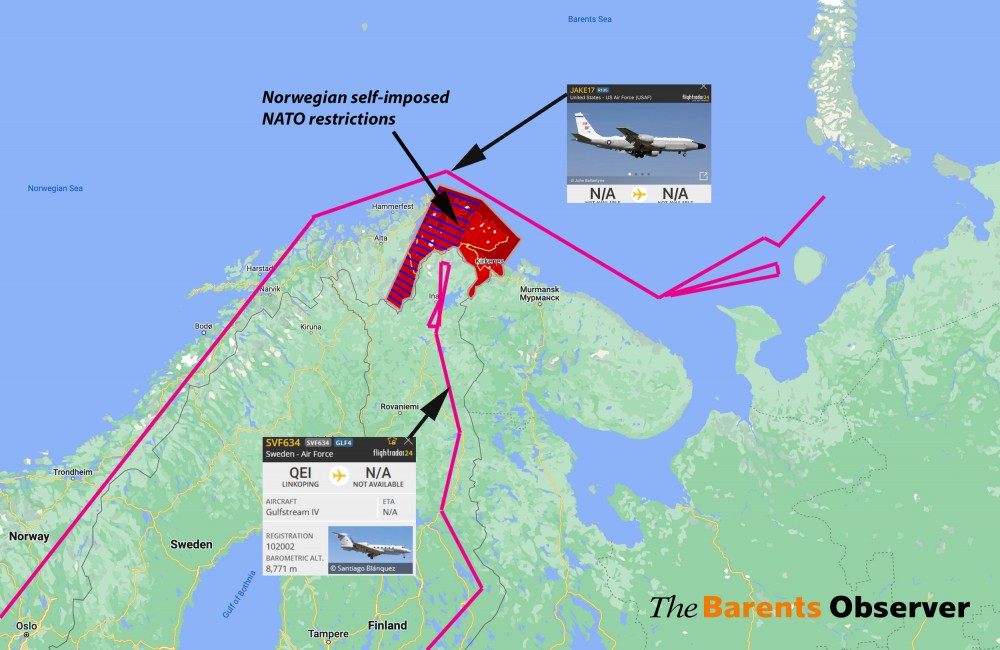

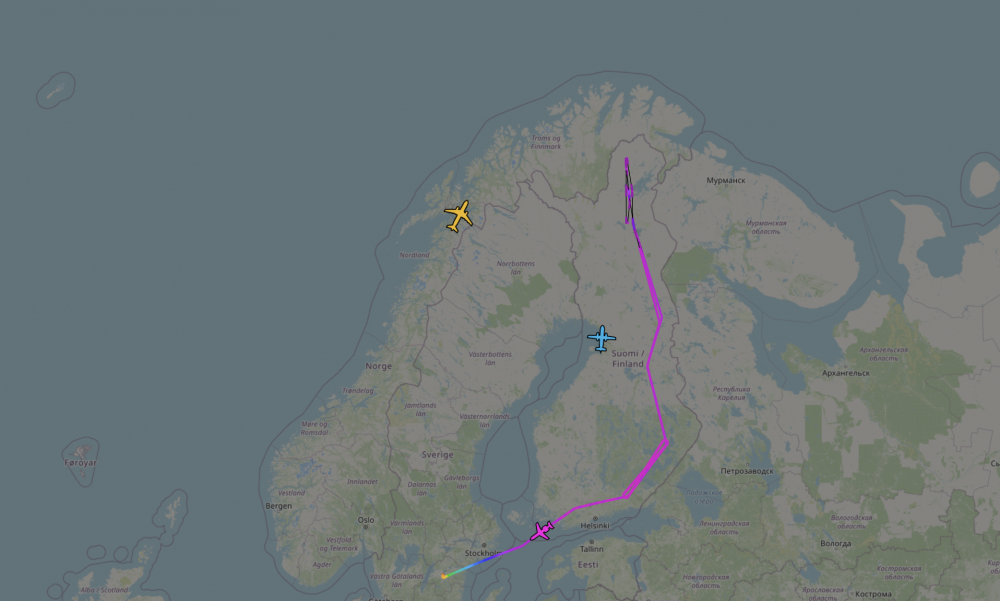

On Tuesday, August 22, both the US Air Force and NATO partner Sweden were in the skies to collect signal intelligence from Russia’s Kola region.

Swedish Air Force dispatched one of its Gulfstream S102B Korpen electronic intelligence (ELINT) aircraft to a flight along Finland’s border with Russia all north to Lake Inari.

Simultaneously as the plane circled several rounds briefly west of the Russian border, a US Air Force RC-135W Rivet Joint took off from the United Kingdom and headed north where it in the late afternoon collected Russian signals from international air space over the Barents Sea north of the Kola Peninsula and east towards Novaya Zemlya.

None of the planes, however, entered Norwegian air space over eastern Finnmark, the border region now in question for lifting self-imposed restrictions.

Norway and Finland have currently separate national systems for approving allied military aircraft in their airspace and issuing diplomatic clearances to allies.

Per Erik Solli suggests the two countries should discuss a common regime.

“Perhaps a cross border regime should be in place instead to have a more holistic approach to allied military aircraft operating in Finland and Finnmark plus those in transit to missions in the Barents Sea,” Solli says to the Barents Observer.

Gradually lifting

Norway, though, has over the years softened its self-imposed military restrictions, also in regards to allied flights.

As a founding member of NATO in 1949, Norway did not allow allied military aircraft at all to fly beyond 68 degrees North. That restriction was altered in a decade later when a non-fly regime East of 24 degrees became the new norm. That is the air space east of the Porsanger fjord.

Per Erik Solli, himself an F-16 pilot in those days, recalls 1995 when a major revision occurred and the so-called Finnmark restrictions for allied army, naval, and air force were eased up.

“In the last decade several alterations have been made for allied military aircraft flying over Finnmark,” he adds.

“The restriction line is now 28 degrees East (the Tana fjord) and only a hard line for allied fighter aircraft. Foreign military helicopters plus passenger- and transport aircraft can fly over the entire Finnmark region as long as they follow the regime set in place by the Norwegian Air Force.”

It was last fall Norway allowed the US Rivet Joint electronic surveillance planes to fly in Norwegian air space en route to Barents Sea missions, as reported by the Barents Observer.

Between 24 and 28 degrees East

Such missions have to be pre-approved by the Ministry of Defense in Oslo, and the planes follow a route north to somewhere between 24 and 28 degrees East north of Finnmark before entering international airspace. From there, the route goes straight towards the area of interest between the Kola Peninsula, Cape Kanin, and Novaya Zemlya.

The same US Rivet Joint planes started to fly missions over Finnish air space a few weeks before the country officially became a member of NATO on April 4th.

Swedish Air Force’s S102B Korpen took to the skies on Wednesday as well, with a flight pattern more or less similar to Tuesday’s flight to northern Finland. With Russia’s Kola Peninsula in clear view out to the east.

You can help us…

…. we hope you found this article informative. Unlike many others, the Barents Observer has no paywall. We want to keep our journalism open to everyone, including our Russian readers. The Barents Observer is a journalist-owned newspaper. It takes a lot of hard work and money to produce. But, we strongly believe our bilingual reporting makes a difference in the north. We got a small favor to ask; make a contribution to our work.

From Norway, you can Vipps 105 792.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Barents Observer Newsletter

After confirming you're a real person, you can write your email below and we include you to the subscription list.