Russia showed “more caution and restraint” in Arctic over past 18 months, says Norwegian intelligence

A stable Arctic is in Russia’s own interest despite distrust and growing tensions. The powerful Northern Fleet has not acted confrontational in northern areas over the last one and a half year, the FOCUS 2022 threat assessment report by Norway’s intelligence service says.

Norway’s analytical eyes are wide amid Europe-Russia standoff but with a special focus on northern regions. Not strange, Russia’s most powerful navy assets and many of the modern weapons systems are deployed close to the border, which also is NATO’s northern land border with Russia.

For Moscow, the Barents Sea region is also key for developing and testings of new missile systems, submarines, drones and maritime surveillance and sabotage assets.

Tensions, however, are lower up north than in other border regions where Russia meets European neighbors.

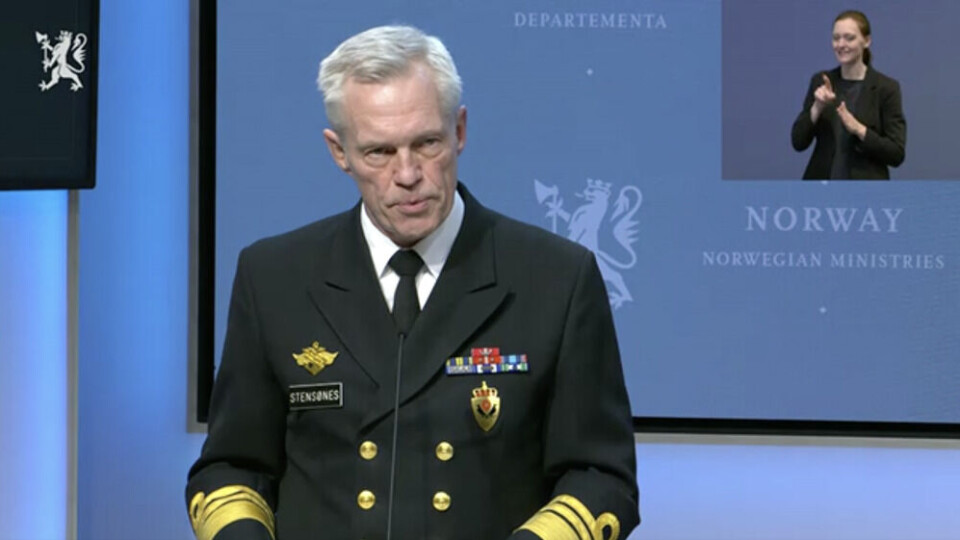

“We see that Russia acts more careful, self-restraint here compared with what they do in the Baltic Sea and especially in contrast to the Black Sea,” says Chief of the Norwegian Intelligence Service, Vice Admiral Nils Andreas Stensønes, in a phone interview with the Barents Observer.

“It is our understanding that Russia wants low tensions and stability in the north. This is in the interest of both countries,” Stensønes states.

The Vice-Admiral is glad to see less confrontational behaviors in the north.

“This is what we strive for and also why we are predictable. We inform, behave professionally and polite when we meet Russian units. We believe this contributes to Russia finding it appropriate to do the same to Norway.”

Asked about which actions were considered provocations in 2020 and before, Nils Andreas Stensønes would not elaborate more than saying “we had some [Russian] interceptions that came too close to our maritime patrol aircraft.”

Norwegian P-3 Orion regularly flies missions in international air space over the Barents Sea in the same way as Russian Tu-142 maritime reconnaissance planes fly missions over the Norwegian Sea and North Sea. Unlike in the Baltic, territorial air space violations have never been reported between the two countries since the end of the Cold War.

The NIS FOCUS 2022 report predicts that Moscow during the chairmanship period of the Arctic Council wants to be seen as a responsible player that for the most will seek pragmatic cooperation with other Arctic States. Russia succeeded Iceland as rotating chair of the Arctic Council in 2021 and will be followed by Norway in 2023.

Less predictability

A challenge for Norway and NATO, however, is the Russian Northern Fleet’s unpredictability. They say one thing and do something else.

Like last August, a group of navy ships led by the destroyer “Severomorsk” sailed from their home port on the Kola Peninsula to Franz Josef Land. The headquarters in Severomorsk published a statement saying that the Arctic group of warships would “take part in several exercises to defend islands and continental territories of Russia in the Arctic, as well as to ensure the safety of maritime navigation and other rules of Russian maritime economic activities in the Arctic zone.”

But from Franz Josef Land, instead of sailing further into Russia’s Arctic zone, the warships suddenly turned 180 degrees and sailed west to the Greenland Sea along the west coast of Spitsbergen, the largest island at Norway’s Svalbard archipelago. From there, the navy group continued south to the Norwegian Sea and stayed for a long time outside the northwest coast of Iceland.

“We are not very surprised that Russia doesn’t inform too much about how to exercise,” Stensønes says. He underlines that a general problem is that notifications are not coming in accordance with the Vienna Document, an international agreement outlining how and where exercises are to take place in order to assure trust-building and avoid misunderstandings.

“Often they do something else than they say,” the intelligence Chief makes clear and adds that this causes less predictability and more uncertainty.

NATO-exercise Cold Response

Although no confrontational actions by Russia’s Northern Fleet have happened over the last one and a half year, the NIS expects trouble when the Norwegian-led large-scale NATO exercise Cold Response kicks off next month in northern Norway.

Russia will present Cold Response as an illustration that NATO is aggressive the report predicts.

“It is also expected that Russia will respond military,” the report states.

“This can range from surveillance to large demonstration of force for strategic deterrence. Measures that could disrupt or complicate the exercise for NATO must be expected,” the report reads.

During NATO’s last large exercise in Norway, the Trident Juncture in 2018, Russia responded with several confrontational measures like extensive jamming of GPS signals in northern Norway that caused serious trouble to civilian aviation. Northern Fleet warships also announced missile shootings with several warning zones along the coast of Norway, including in the same waters as NATO navies were sailing. In the final days of Trident Juncture, Russia made an exercise area for rocket shootings just 40 kilometers north of Berlevåg and Gamvik on Norway’s Barents Sea coast.

“Will escalate tensions”

On February 10, Chairman of the Committee of Senior Officials in the Arctic Council, Russia’s Ambassador-at-Large Nikolai Korchunov made clear in an interview with RIA Novosti that Cold Response “will escalate tensions and increase the risk of accidental incidents and unintended escalations.”

He argued that the NATO exercise takes place above the Arctic Circle and repeated Moscow’s standard saying that “there are no issues in the Arctic that require a military solution.”

Cold Response will have its main military activities area in Often area between Narvik and Harstad and in the waters outside. This is about 600 kilometers away from the Russian border.

Meanwhile, as reported yesterday by the Barents Observer, Russia’s Northern Fleet has started to train with its new Tor-M2DT missile-to-air system just a few tens of kilometers from the border to Norway in the Pechenga valley, one of the most heavily armed military districts in northern Russia.