Cold War heritage secured, but now comes new wave of maritime reactors

The floating nuclear power plant «Akademik Lomonosov» now under tow towards Murmansk marks the start of a comprehensive utilization of nuclear energy in the Russian Arctic. New submarines, surface warships, icebreakers, seabed- and onshore mini-reactors as well as nuclear-powered military weapons are all queuing up in record speed. The Barents Observer gives you the overview.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

«627 NOR» reads the white-painted tag on the support pillars holding one of the massive compartments at the concrete pad. The tag tells the story about a multi-million financial grant given by Norway to cover costs for safe decommissioning of this old November-class submarine. Norway co-financed scrapping of five old submarines. Once upon a time designed and built as part of the Soviet Union’s war-machine for retaliation if NATO attacked first. «627 NOR» is just one of many reactor compartments lined up for long-term storage, all labeled with radiation danger signs.

25-years of international cooperation safeguarding radioactive scrap on the Kola Peninsula is a success story. No doubt. By the end of the Cold War, some 120 retired nuclear powered submarines were rusting at naval bases and shipyards along Russia’s Barents Sea coast and in Severodvinsk by the White Sea. Most of them with the lethal dangerous spent nuclear fuel still inside the reactors.

Today, they are all defueled, scrapped and most reactor compartments are already safely stored onshore.

Although also other countries participated with cash in the joint efforts to decommission the big number of Cold War submarines, the main costs were covered by Russia itself. When filled up, the long-term storage complex here in Saida Bay will hold 150 reactor compartments and 25 units with compartments of nuclear service vessels. Like the «Lepse» which was mored just north of Murmansk before towed to scrapping a few years ago. Environmentalists named the vessel a possible «sinking radioactive nightmare.»

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

No wonder people were worried. What would happen if radioactivity started to leak out to the Barents Sea, a crucial fishing ground for both Norway and Russia. And the European Union which gets most of its bacalhau-dinners from the high north. Clean and healthy are selling arguments of growing importance for the seafood industry. In 2017, Norway alone exported seafood worth 94,5 billion kroner (€9,74 billion). For Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, quality of seafood processing was top on the list when he visited Murmansk in April.

Making more headline news, though, are the massive plans for utilization of nuclear energy for other civilian purposes.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Rosatom in lead position

The sharp cut in numbers of maritime reactors, however, have now been put in the reverse gear. Three post-Cold War nuclear powered submarines are already sailing, one Borei class ballistic missile submarine and two multi-purpose submarines of the Yasen class. Many more are under construction (see below). New icebreakers, even more powerful the the existing, are within a few years ready to sail north from the shipyard in St. Petersburg.

At a Moscow meeting in last week of April the State Commission for Development of the Arctic, headed by Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, discussed how to place the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom in a key position. Giving Rosatom broader power of the Russian Arctic will provide for better development of infrastructure, the Commission believes. Supported by President Putin, a new law giving Rosatom a management role for the development of Northern Sea Route will soon be submitted to the State Duma.

For Rosatom, this means much more than keeping the sea route north of Siberia open for shipping with the help of nuclear powered icebreakers. Researchers and designer are both brushing dust of old Soviet era plans and creating new ideas, especially on how to use nuclear energy for exploration of natural resources.

Institutes like Iceberg and Rubin, both working in cooperation with United Shipbuilding Corporation, have launched new Arctic projects for Rosatom.

Subsea reactors for petroleum drilling

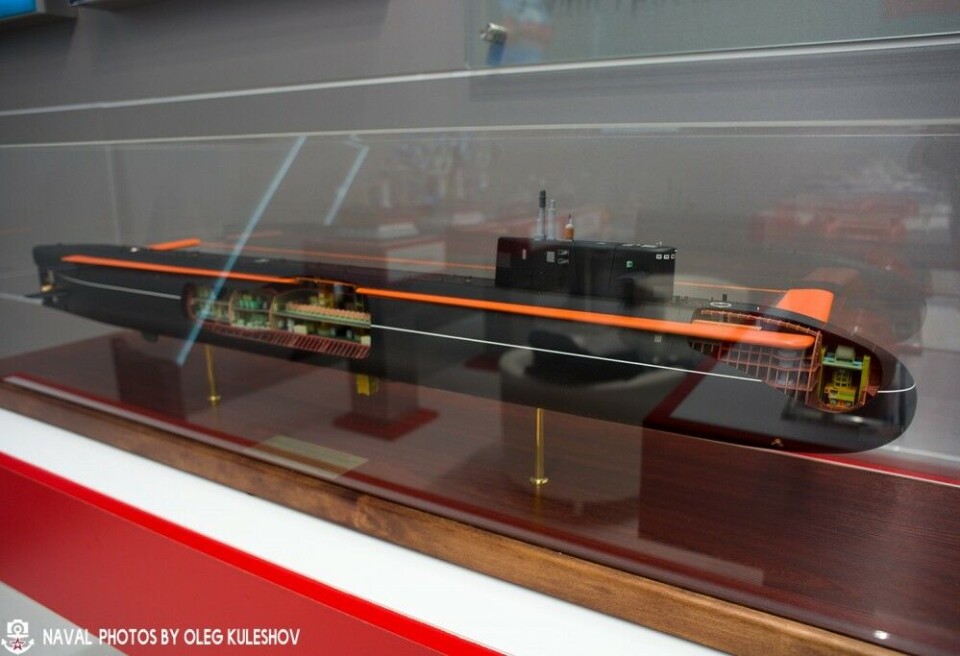

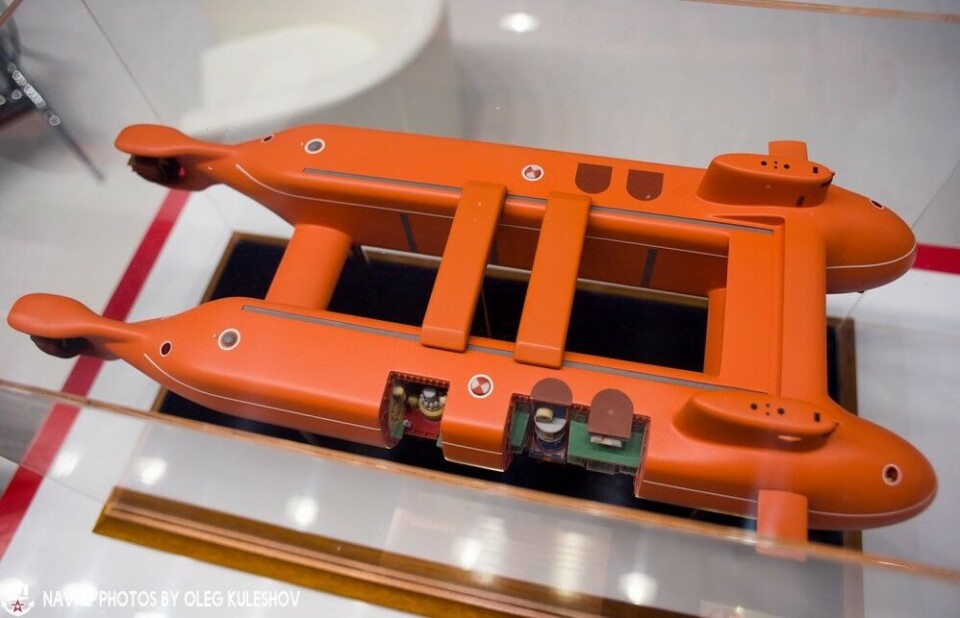

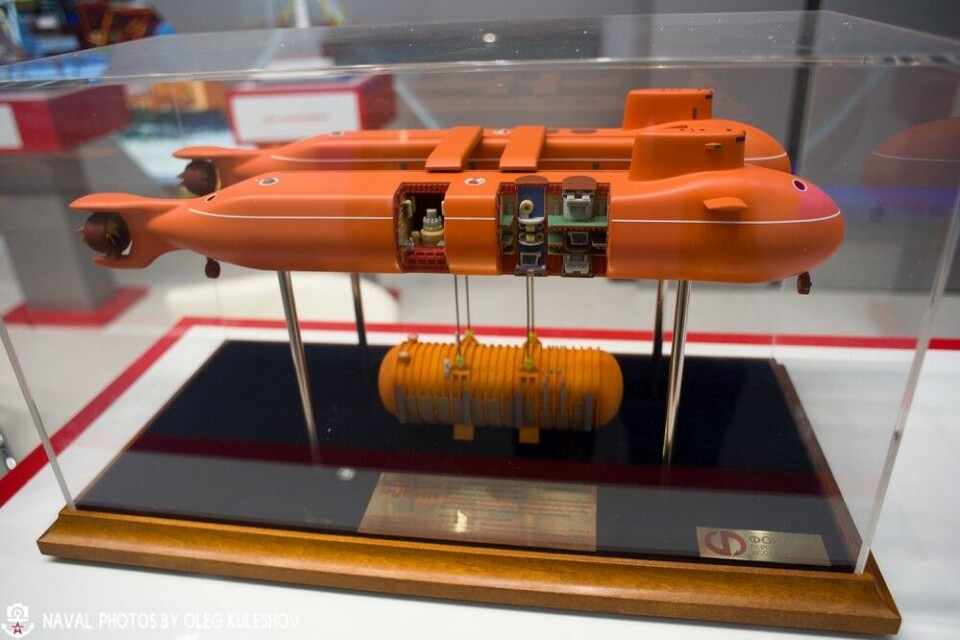

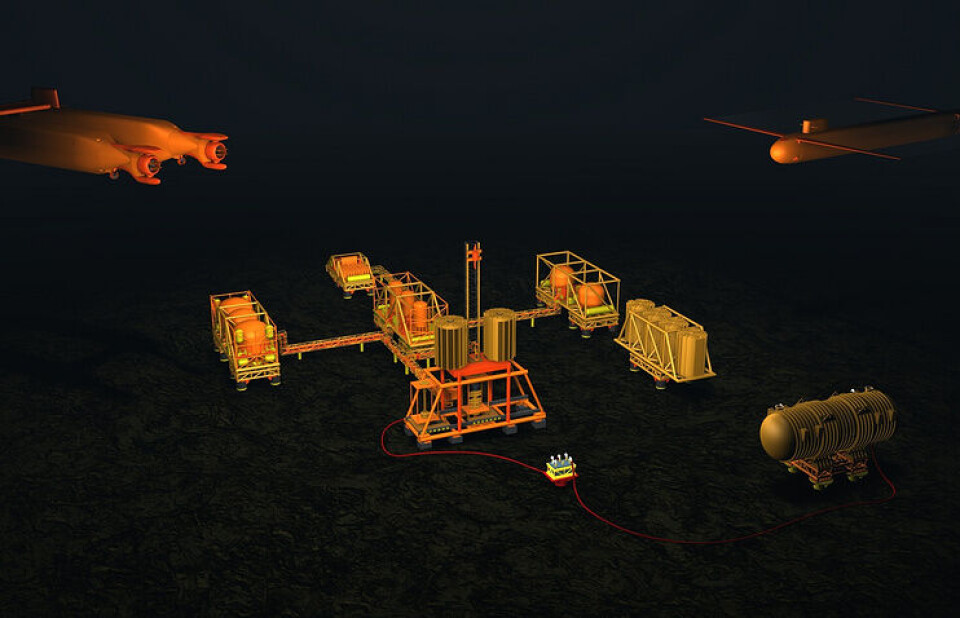

For ice-covered waters, like the northeastern Barents Sea, the Kara Sea and the Laptev Sea, seabed infrastructure for autonomous drilling and production for oil- and gas are being developed. The concept was presented at the conference «Arctic - Territory of Dialogue» held in Arkhangelsk last winter. Such installations will drill both vertical and horizontal, operate satellite drillings- and pumping stations, all powered by a small reactor placed on the seafloor.

A set of nuclear powered mini-submarines with lifting capacities will provide for installation and maintenance of the new 24 MW power modules. Operational time without human presence is at least 8,000 hours, Rubin Central Design Bureau for Marine Engineering informs. The Bureau is no beginner in such work, having all four generations of the navy’s ballistic missile submarines on its reference list.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Rubin says their St. Petersburg design office has focused on deep-sea operations since 2015. Head of the project team with the Russian Federation for Advanced Studies, Viktor Litvenenko, recently told TASS about the timeframe. «This work, according to our calculations, can take about 4-5 years, during which time we will be able to create a pilot demonstration version.» Litvenenko says such pilot reactor system first has to be tested in water-pools, thereafter in shallow and deep water.

«Rosneft and Gazprom have expressed readiness to work with the project,» he says. «It is profitable to invest such installations.» The advantages of using nuclear reactors to power subsea oil- and gas activities are the possibilities to work year-around, under the ice, with fewer risks and in any weather condition, Viktor Litvenenko argues.

I’m especially worried about the transport and use of the nuclear barge in Arctic conditions, far away from technical help in case of accident.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Mining on the Arctic seafloor is another area where utilization of autonomous installations powered by nuclear reactors can be used, the Rubin bureau suggests. Even nuclear-powered submarines forp.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}seismic surveys sailing under the ice are included to the list of Arctic shelf development plans.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

In February, Barents Observer reported about the proposal to take use of mini-reactors for providing electricity to the projected Pavlovsky mine on the southern island of Novaya Zemlya. Such reactor would be even smaller than the once designed for subsea oil- and gas operation. Rosatom’s subordinated NIKIET institute estimates each reactor to be 6,6 MW.

Pavlovsky mining project, exploring zink and lead, is owned and developed by Rosatom itself and will be the first mining project on the closed island formerly infamous for being the Soviet Union’s largest testing range for nuclear weapons.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

«Akademik Lomonosov»

Russia’s first floating nuclear power plant, the «Akademik Lomonosov» will stay for a year at Rosatomflot’s service base in Murmansk. Here, uranium fuel rods will be loaded into the two reactors. Test-runs will last for about a year, before the barge will be towed across the Barents Sea, along the Northern Sea Route to Pevek in the far east of Siberia.

Nils Bøhmer, a nuclear safety expert with the Bellona Foundation in Oslo, is worried about introducing floating nuclear power plants to such far away regions as the north coast of Siberia. «I’m especially worried about the transport and use of the nuclear barge in Arctic conditions, far away from technical help in case of accident. The Arctic is vulnerable for radioactive contamination and a possible clean-up operation will be difficult,» Bøhmer says. He is also concerned about risk of terror.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Dawn Stover, Contributing Editor to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, describes the pros and cons on safety for a floating nuclear power plant. She says it «… would probably be safe from earthquakes, but storms could be a threat, and accident response would be slow in remote Arctic areas.» Being on the sea, Stover tells, «an offshore plant would have plenty of cooling water readily available.» A safety concern, though, is backup power. The plant «might not have access to off-site backup power, and it would be more difficult to contain any radioactive releases than when an accident occurs at a land-based plant.»

Rosatom has further plans to build a series of similar floating nuclear power plants, both for use in remote Arctic regions and for leasing to other countries. The second plant to be built is planned for Vilyuchinsk, a town on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

With «Akademik Lomonosov» connected to the Pevek grid, likely some time during 2019, Rosatom also proves the success to a project that has been on-again, off-again for the past 25 years. Being a paper-plan for more than a decade, the barge was first laid down in Severodvinsk in 2007. A year later, the work was moved from the yard by the White Sea to Baltic Shipyard in St. Petersburg where the reactors, turbogenerators, turbines and living quarters for the crew were installed.

The two reactors are a modified version of the KLT-40 reactors designed in the 1970s and used on board the fleet of nuclear powered icebreakers.

Maintenance and fuel-changes

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

For transport of nuclear waste, construction of a special purpose ice-classed ship will start in 2020. On board, it will be cargo space for 40 to 70 containers for both spent nuclear fuel and solid radioactive waste. The ship will be sailing the Northern Sea Route, but could as well make voyages up the Siberian rivers of Ob and Yenisei, where several of Russia’s nuclear facilities are located, like the storage and planned reprocessing plant in Zheleznogorsk north of Krasnoyarsk.

During the last two or three years we have seen some more incidents.

A key question is where major maintenance work, mid-time upgrades, changing uranium fuel and repair in case of incidents will take place. Not only for the floating nuclear power plants, but also the coming seafloor reactors for seafloor petroleum installations. There are no shipyards anywhere between Murmansk and the Kamchatka Peninsula. If not to create a new nuclear-service centre in the Arctic, such work will have to be done at the existing yards and bases.

Atomflot just north of Murmansk serves the fleet of icebreakers and spent nuclear fuel support vessels. A challenge, though, is the already lack of berths to serve the new giant icebreakers which will be put into service within the next few years. For radiation safety reasons, and terror threats, this group of vessels can’t make port call to quays other places in Murmansk, Russia’s hub for Arctic shipping.

Other options for serving the new nuclear maritime installations are the shipyards. On Kola, both Nerpa and yard No. 10 Shkval have experience with changing uranium fuel and maintenance or decommissioning of reactors. By the White Sea, the two large yards in Severodvinsk could do the same, but here priority is given to military vessels.

«We have learned from the past»

For Norway, neighboring the Kola Peninsula, increased nuclear activities motivates for open dialogue about risk assessments and preparedness.

«Our long-lasting cooperation with Russian authorities about nuclear safety has contributed to more focus on environmental considerations, waste management and compliance with international regulations and principles,» says Ole Harbitz, Director of the Norwegian Radiation Protection Authorities (NRPA).

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has contributed with about 2 billion kroner (€207 million) to a wide range of nuclear safety projects in northwest Russia since 1994. Handling of spent nuclear fuel, solid radioactive waste, improved power plant control systems, physical protection, removing radioactive batteries from Arctic lighthouses and scrapping of old submarines have been given priority.

For Harbitz, the open-door dialogue on safety and preparedness is the best way to meet renewed focus on maritime reactors. He thinks Russia is much better prepared to handle nuclear waste now compared with the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union. «Both Russia and the international community have better regulations, and have waste management plans available before new activities can start,» Ole Harbitz says.

Measuring radioactivity

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

At NIBIO Svanhovd, an environmental research centre in the Pasvik valley, the radiation watchdog has an emergency preparedness and response station. Head Engineer Bredo Møller keeps a close eye on what his measuring instruments might discover in the air over the borderland. Møller sits less than a kilometer from the Russian border.

«This sampler is one out of six air-filter stations we have situated along the coast of Norway. We analyse the filter in a laboratory once a week for radioactive nuclides,» Bredo Møller explains. This station was the first to measure the cloud of tiny amount of radioactive iodine that spread over most of Europe last year.

«Every now and then we see something out of normal. Then we alert our own organization, we post our findings online and inform the public,» Møller tells. Established 20 years ago, the emergency response unit has seen an increase in cases lately. «The normal was to measure some increased radioactivity one time every year over the last 10 or 20 year, but then, during the last two or three years we have seen some more incidents. Like in 2017, when we had the special case with ruthenium and also a few cases of radioactive iodine.»

Bredo Møller underlines that we are talking about very tiny small measurments, far from posing any harm to human health. It is also hard to trace the radioactivity to any particular source or country.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Most of the Russian Northern Fleet’s bases with nuclear powered submarines are in a distance of less than 130 kilometers from the Norwegian measuring station. Zapadnaya Litsa, where you find both a few submarines, but also the largest Cold War dump-site with nuclear waste, is only about 80 kilometers away.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Director Ole Harbitz admits that more maritime reactors in northern Russia is a challenge for the Norwegian radiation agency. «This is the reason why we argue the need for continued dialogue with Russian authorities, both to get knowledge about risks and about measures which can reduce the threat of accidents,» he says to the Barents Observer.

More nuclear powered submarines along the coast of Norway means increased risk of accidents. The NRPA has together with other authorities established a study group assigned to analyse how iodine tablets should be made available to the population. Iodine tablets can be used as a preventative measure against thyroid cancer, especially for children and young people.

Little transparency

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Nils Bøhmer fears for the future. «Although Russia right now has a better economy than in the chaotic 90ties, it does not mean we can relax. With such massive plans Rosatom now creates, nuclear emergency teams working in the Arctic should fasten seatbelts and stay on alert,» Bøhmer warns. «There is still little transparency into Russia’s nuclear industry, and we haven’t been presented any long-term plans for how the radioactive waste from all this new reactors are to be handled.»

Another reason to worry, according to Bøhmer, is the lack of plans for what to do with all the installations after the oil, gas- and mineral explorations are over. «We have to ask; will we within some few tens of years again see a need for large-scale international cooperation to safeguard abounded nuclear installations?» Nils Bøhmer asks rhetorically.

More nuclear installations requires better anti-terror enforcement and physical security. A rather unnoticed news was published by TASS earlier in April. According to the news agency, quoting the press-service of the National Guard Rosgvardia, about 200 offenses at nuclear facilities in the Arctic were stopped in the first three months of 2018.

«Only in 2018 Rosgvardia prevented more than 200 attempts to commit unlawful acts on these objects,» the press-service said pointing to facilities like Kola- and Bilibino nuclear power plants and Rosatomflot’s objects.

Rosgvardia soldiers, including Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov’s «Flying Squad» recently exercised anti-terror operation on one of the laid-up nuclear powered icebreakers at Atomflot service base.

41 nuclear powered vessels

As of today, Russia’s Northern Fleet has 35 nuclear powered submarines in operation. 32 of them are based on the coast of the Barents Sea from the Kola Bay to the Zapadnaya Litsa fjord. One, the «Dmitry Donskoy» is normally based at Belomorsk naval base in Severodvinsk by the White Sea, but this spring the giant Typhoon submarine has been in dry-dock at naval yard No. 82 in Safonovo north of Murmansk. The second vessel in the Yasen class, thep.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}«Kazan» is still test-sailing out of Severodvinsk. Also, the «Sarov» special purpose submarine is sailing out from Severodvinsk.

Additionally, the fleet has one nuclear powered surface vessel, the «Pyotr Veliky» battle cruiser.

At the start of his third term as President, Vladimir Putin in 2012 ordered the government to ensure the development of the navy, primarily in Russia’s Arctic zone and in the Far East. Putin got what he wanted. Last October, Commander-in Chief of the navy, Admiral Vladimir Korolyov presented the results. «Speaking about the navy’s surface vessels, I can tell the following. In 2013, it was 5,900 days [of sailings]. In 2014, already 12,700, in 2015 – 14,200, in 2016 – 15,600, and in 2017 - 17,100 days,» the Admiral said. NATO officials confirmed the sharp increase in sailings, claiming Russian submarine activity to equal Cold War levels. In Norway, the Ministry of Defense told the Barents Observer earlier this winter that allied nuclear powered submarines are sailing inside, and surfacing, Norwegian waters «3 to 4 times per month» with the majority in the north.

Sailing out from Murmansk, Russia has the world’s only fleet of civilian nuclear powered vessels. As of today, this fleet consists of four icebreakers, and might see the container vessel «Sevmorput» soon re-commissioned. The icebreakers’ service base Atomflot is also the port where «Akademik Lomonosov» - the first floating nuclear power plants - will be moored for a year while the reactors are being tested.

Could be twice as many reactors

Including maritime nuclear powered vessels under construction and the planned new, Russia might within the two next decades at least get twice as many sea-based reactors compared with today in the Arctic.

Currently, 12 new nuclear-powered submarines are in pipe at the Sevmash yard in Severodvinsk. These include five Yasen class and five Borei class. Some of them will be transferred to the Pacific Fleet, while others will sail for the Northern Fleet. Originally, all Borei class submarines where to be commissioned to the navy by 2020. However, construction and testing take longer. Like for the next Borei submarine, the «Knyaz Vladimir» supposed to set sail last year. Deputy Commander of the Russian navy, Admiral Viktor Bursuk, now told journalists that the fleet would not receive the new ballistic missile sub before 2019.

The future plan for reactor-powered navy vessels includes both a new class of destroyers as well as a new aircraft carrier. A governmental decision on whether to go ahead with the Lider giga-icebreaker project could be taken within some few years. A more secretive on-going naval reactor program concerns the Poseidon (Status-6) underwater drone President Vladimir Putin announced in his state of the nation speech in March. It is known that at least one prototype is built, but where in the Arctic, and how many would possible be deployed, is more uncertain.

In total, at least 18 nuclear reactor powered ships and installations are under construction and another 20 to 40 reactors are on the table for talks. The future of Russia’s Arctic is nuclear-driven.

| Number | Class | Names |

|---|---|---|

| Submarines | ||

| 1 | Borei | «Yuri Dolgoruky» K-535 |

| 6 | Delta-IV | «Ekaterinburg» K-84, «Bryansk» K-117, «Karelia» K-18, «Novomoskovsk» K-407, «Verkhoturye» K-51, «Tula» K-114 |

| 1 | Typhhon | «Dmitry Donskoy» TK-208 |

| 4 | Sierra | «Kostroma» B-276, «Carp» B-239, «Nizhniy Novgorod» B-534, «Pskov» B-336 |

| 3 | Victor-III | «Obninsk» B-138, «Daniil Moskovkiy» B-414, «Tambov» B-448 |

| 3 | Oscar-II | «Voronezh» K-119, «Smolensk» K-410, «Orel» K-266 |

| 6 | Akula | «Tigr» K-154, «Pantera» K-317, «Vepr» K-157, «Volk» K-461, «Leopard» K-328, «Gepard» K-335 |

| 2 | Yasen | «Severodvinsk» K-560, «Kazan» K-561 |

| 1 | «Losharik» AS-12 | |

| 2 | Uniform | AS-13, AS-15 |

| 3 | X-ray | AS-23, AS-21, AS-35 |

| 1 | «Orenburg» BS-136 | |

| 1 | «Podmoskovye» BS-64 | |

| 1 | «Sarov» | |

| 1 | Battlecruiser | «Pyotr Veliky» |

| 4 | Icebreaker | «Yamal», «50 let Pobedy», «Vaigash», «Taymyr» |

| 1 | Lightercarrier | «Sevmorput» |

Sources: Barents Observer, Flot.com, Covert Shores, Wikipedia.

| Numbers | Class | Names |

| Submarines | ||

| 5 | Borei | «Generalissimus Suvorov», «Knyaz Pozharskiy». Pacific Fleet: «Knyaz Vladimir», «Imperator Aleksandr III», «Knyaz Oleg». |

| 5 | Yasen | «Novosibirsk», «Krasnoyarsk», «Arkhangelsk», «Perm», «Ulyanovsk» |

| 1 | «Khabarovsk» | |

| 1 | «Belgorod» | |

| 1 | Battle cruiser | «Admiral Nakhimov» |

| Icebreakers | ||

| 3 | LK-60Ya | «Arktika»,«Sibir», «Ural» |

| 1 | FNPP | «Akademik Lomonosov» |

| 1+? | Weapon | Poseidon (Status-6 or KANYON) nuclear-powered UAV |

| Numbers | Class | Type |

| 4 | Borei-B | Submarine (SSBN) |

| 8 | Lider | Destroyer (Project 23560) |

| 1 | Shtorm | Aircraft carrier (Project 23000E) |

| 7 | Floating nuclear power plants (FNNP) | |

| ? | Weapon | Poseidon (Status-6 or KANYON) nuclear-powered UAV |

| ? | SHELF | Seabed mini-reactors |

You can help us…

…. we hope you enjoyed reading this article. Unlike many others, the Barents Observer has no paywall. We want to keep our journalism open to everyone, including to our Russian readers. The Independent Barents Observer is a journalist-owned newspaper. It takes a lot of hard work and money to produce. But, we strongly believe our bilingual reporting makes a difference in the north. We therefore got a small favor to ask; make a contribution to our work.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px ‘Helvetica Neue’; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 12.0px}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}